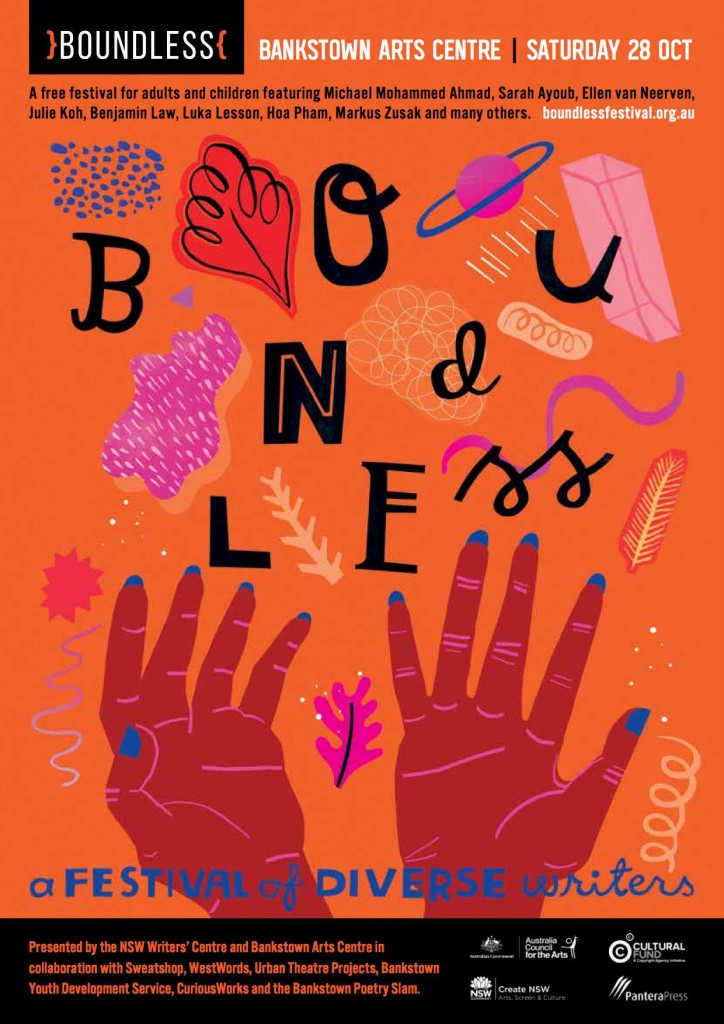

It is difficult to convey just how excited I was when I learned that a festival devoted to Indigenous and culturally diverse Australian writers would be taking place this year. I immediately blocked off the date in my calendar, eagerly followed announcements of the festival’s lineup and official program, and counted down the days. On the long-awaited morning, I cheerfully thanked my spouse in advance for minding our toddler, clambered into my car, and sped off to the western suburbs of Sydney to have my mind blown by the incredible experience that would be Boundless 2017.

My eagerness may seem excessive, but I had good reason: there have been a few race-related controversies on the Australian literary scene recently—enough to give anyone who identifies as a writer of color (in my case, ethnic Chinese from Indonesia and Singapore) pause. Last year’s Brisbane Writers Festival featured a keynote speech from Lionel Shriver defending the right of writers, especially those from “traditionally privileged demographics”, to co-opt perspectives not their own. When Sudanese-Australian activist Yassmin Abdel-Magied walked out in protest and supporters took to their blogs and Twitter in criticism, many commentators dismissed their disapproval as “a silly frenzy”, terming Shriver’s speech a call for “empathy, not cultural appropriation.” At this year’s Sydney Writers’ Festival, the Australian radio host Michael Cathcart interviewed African-American writer Paul Beatty to similar furor, causing Trent Shepherd, an Indigenous lawyer, to stand up and challenge “white Australia to look at themselves.” Mere days before Boundless, irate high school students attacked Indigenous writer Ellen van Neerven via email and various forms of social media over the inclusion of her poem “Mango” on a state-wide exam. One student tweeted a picture of a chimpanzee at a typewriter, captioned “Leaked Image of the Author.”

Hence my elation at the prospect of attending a literary festival that promised to make diversity the norm for at least one day—to shift those on Australia’s literary margins to the center rather than treating them as the exceptions on a predominantly white Australian writing scene. I was also curious: how would the dynamics differ from other literary festivals I had attended? Would they differ? I hoped so, even as I wasn’t sure I could pinpoint exactly what those hopes were. But perhaps a lack of pinning and pointing was precisely what I craved. Perhaps I was tired of attending panels where writers of “distinctive backgrounds” were assumed to be spokespeople for their particular culture or race (as did in fact occur at a festival I attended earlier this year when a panel moderator innocently deployed the term “your people” in a question directed at China-born writer Isabelle Li).

One of the things I appreciated most about Boundless was the frank discussion I couldn’t imagine taking place at a mainstream festival without a higher degree of self-censorship. Writers aired frustrations about the problem of white gatekeeping and mediation of non-white voices in the literary industry, not to mention the pressure to cater to white audiences as a matter of course. On a panel about writing for the stage, Andrea James, a respected playwright of Indigenous Yorta Yorta and Kurnai descent, spoke about the compromise necessary in staging a play at all: “For my parents’ generation in particular, we’re asking them to come into spaces they weren’t allowed to go. So even putting on a play in a theater is a compromise.” Though sometimes she contemplates performing in different spaces—ones where people from her community might be more comfortable—she then finds herself thinking, “Fuck you. We paid for this space with our lives and our blood.”

The problems inherent in the white curation of non-white voices and the desire of white writers and artists to appropriate experiences not their own also came up in a session called “Deadly and Hectic.” The culmination of a week-long dialogue organized by the Sweatshop Literacy Movement between four writers of Indigenous descent and four writers of migrant and refugee backgrounds, the conversation began with the writers talking about whose stories they gave themselves permission to write. “We are the Other with a capital ‘O’; we are the back corner of the book shop; we are the addition, we are the afterthought”: in this way did Evelyn Araluen—a writer of Bundjalung descent, born and raised on Dharug country—describe the session’s participants before going on to note that the dialogue was very possibly the first time where writers from these two groups were speaking directly to each other in public without mediation by a white person. In the course of the conversation, Tongan-Australian writer Winnie Dunn observed that in general white people didn’t seem to have the same reservations as the session participants did, instead giving themselves permission to write whatever and whoever they wanted: for example, the white Australian comedian Chris Lilley and his demeaning brownface portrayal of Tongan youth.

An afternoon panel featured some of the most critically acclaimed writers of color on the Australian literary scene—Ellen van Neerven, Julie Koh, Michael Mohammed Ahmad, and Peter Polites, not to mention the session’s moderator, screenwriter and journalist Benjamin Law. Among the topics discussed were their impressions of Australian literature growing up and the non-Australian works and writers that have shaped what they write. Peter Polites’ answer regarding the first: “a book set in the bush; a book about World War II; and ‘man has feelings.’” Also on the table as conversational fodder: what is “whiteness”? Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s working definition drew on work by bell hooks, Ghassan Hage, and Malcolm X. Benjamin Law asked Ellen van Neerven why people abroad seemed to know more about Indigenous Australian literature than people in Australia. Her reply: that people in this country thrive on the supposed absence of Indigenous people. “It wouldn’t make sense,” van Neerven continued, “if the people in this country were well-read in Alexis Wright or Kim Scott because then they would really question how they’re engaging with this country and its first peoples.” An audience member asked the panel members how they dealt with the assumption that white writers had universal relevance and minority writers only had relevance to a particular demographic. In response, Julie Koh expressed dismay at being consistently asked to appear on diversity-focused panels at festivals, despite the fact that the scope of her writing extends beyond race.

Boundless was not without uncomfortable moments. Critiques of white privilege and authority on the nation’s literary scene were expressed far more openly than I’d ever seen at any writers’ festival I’d attended prior to this one. I admired this, and yet found myself squirming as I wondered how white attendees were reacting to such criticisms. Then again, how many literary festival sessions had I been to and read about—not just in Australia, but Asia as well—where the sensibilities of non-white, non-western attendees weren’t taken into account? Why did I feel obliged to be hypersensitive to white sensitivities, when the reverse rarely seemed to happen?

During the keynote session, Michael Mohammed Ahmad even took the trouble to explicitly address the issue: “If you read our writing,” he said, “you’ll find we actually love white people. We marry them, we’re friends with them, we’re related to them. A lot of good white people helped organize this festival. What I hate is white privilege, xenophobia, imperialism, colonialism […] and the white people that we love hate those too.”

If the festival does continue past its inaugural year, should participants have to worry about being accused of reverse racism, especially since such a festival, to a large extent, is predicated on the supposition that white racism, not its reverse, is the norm?

A few days after Boundless, I interviewed three of the festival participants via phone and email to get their impressions of the event. Benjamin Law reiterated just how diverse Australia is: “We’re home to the oldest living, surviving and thriving human cultures and communities bar none […] About half of us have parents born overseas, a quarter of us are migrants, and one in five speak languages other than English at home. And yet that’s rarely the image of Australia we export or tell ourselves […] given the disproportionate primacy of Anglo stories in our culture, Boundless felt like a healthy corrective.”

Julie Koh was excited about being in the same space as so many of the other movers and shakers of color in the industry, yet felt that there was “still a long road ahead.” But “having us all in the same place meant we could engage in constructive conversations about how to move forward together.”

Michael Mohammed Ahmad—who together with fellow Sweatshop Collective member Winnie Dunn helped conceive the idea for the event when they were approached by the NSW Writers Centre—stressed the importance of examining what aspects of the festival succeeded and why, rather than uncritically calling the event a success. “The feedback I got from writers of non-white backgrounds was this: what do we do next as a collective of people from minorities? How about a festival not just for diverse writers, but entirely produced and run by diverse writers?” Boundless, he noted, was an event, but “liberation and freedom and justice are not events, they’re processes […] We need to have hard discussions. People may get offended and upset, but if we really want to reach freedom and justice, we have to go to these hard places and be honest.”

Tiffany Tsao is a writer, translator, and Asymptote’s Australia Editor-at-Large. After spending her formative years in Singapore and Indonesia, she moved to the US where she received her Ph.D. in English from UC-Berkeley. She now lives in Sydney, Australia. Her writing and translations have appeared in LONTAR, The Sydney Review of Books, the anthologies Contemporary Asian Australian Poets and BooksActually’s Gold Standard 2016, and elsewhere. Her debut novel, The Oddfits (AmazonCrossing), was published in 2016.

*****

Read more dispatches on the Asymptote blog: