Every month, batches of books arrive fresh on the shelves of bookstores around the world. Our team has handpicked three exciting new reads to help you make up your minds on what to sink your teeth into, including novels from Italy, Brazil and Norway.

Dust by Adrian Bravi, translated from the Italian by Patience Haggin, Dalkey Archive Press.

Reviewed by Lara Norgaard, Editor-at-Large, Brazil.

“‘How long will I have to flail about, drowning in the world of the microscopic?’”

This is one of the many questions that the narrator, Anselmo, of Adrian Bravi’s novel Dust anxiously asks himself while coping with his total phobia of dust. The depth of his internal interrogation hinges on the word “microscopic”: Anselmo faces not the literal question of clean living, but instead the concept of infinite accumulation and infinite loss—of seconds and minutes, of words and ideas, of skin and hair and other shavings of the physical self.

To read Patience Haggin’s forthcoming English translation of Dust (Dalkey Archive Press, October 2017) is to slowly sink into an ocean of everyday minutiae. The book centers on Anselmo, a librarian living with his wife Elena in the fictional city of Catinari, Italy, and his daily routine of cataloguing books, obsessively dusting surfaces, and frequently writing letters that invariably never reach their destination.

What gives this novel its power is not the literal subject matter of the book, which often threatens to overtake the prose in its tedium, but instead the artful language that invites us to meditate conceptually on the simple life represented. Anselmo, at one point, compares his monotonous work cataloguing books to that of a “simple mortician sorting bodies for burial according to their profession”; at another moment, his wife Elena says that reading newly published books is akin to, “‘studying smoke your whole life when you’ve never seen fire.’” These metaphors broaden a seemingly narrow scope, bringing us closer to fully imagining humanity’s constant and immense decay.

The original title of the work is La pelusa, the Spanish term that Anselmo learns to describe dust. A mysterious Argentine man who shares the author’s name, Adrian Bravi, suggests the word pelusa to the narrator. The real Adrian Bravi (the author, not the character) was born in Buenos Aires but lives in Italy, and this novel navigates Bravi’s personal tie to the two countries, an interesting affinity that many share due to the long history of Italian immigration to Argentina. Bravi often alludes to Italian literature, most notably in his references to the famed poet Leopardi. The very content and structure of Bravi’s prose also carry echoes of Argentine literature. Anselmo’s perpetually lost emails and letters (always addressed to questionably real recipients) reimagine the epistolary novel much along the same lines as Ricardo Piglia’s Artificial Respiration. And the image of a tortured librarian sorting books conjures up the image of Jorge Luis Borges in his later years, blind and unable to read, when he served as the director of the National Library of Buenos Aires.

Bravi’s very conceptual style of writing does occasionally fall flat. Elena, forever inadequate to misogynistic Anselmo, passively accepts her husband’s emotional abuse and falls into alcoholism. The unhealthy relationship carries larger significance: Anselmo’s isolation from his wife parallels his solipsistic letter writing. However, it is Anselmo’s perspective that dominates the narrative, and Bravi thus deprives the female character of a voice—and of agency—in the story of an abusive marriage. Reading the repeated descriptions of Elena’s resigned substance abuse alongside Anselmo’s vitriolic demands for her to clean leads to frustration, not epiphany.

Still, Dust is an extremely worthwhile and attentive portrait of abstract ideas. Haggin’s English translation captures the multiple levels of meaning that resonate throughout the novel, and she maintains Bravi’s careful repetition of words and images. The result is a subtle text, one in which plot might plod forward slowly like titles being catalogued, but meaning settles in endless layers like dust collecting on the surface of an unread library book. Every few pages, a surprising character, a compelling quote, or even a single, unexpected word arrives in a gust, scattering our futile search for orderly understanding. Then, exhilarated, we find ourselves drowning in the infinite microscopic once more.

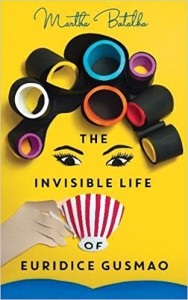

The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao by Martha Batalha, translated from the Portuguese by Martha Batalha, Oneworld Publications.

Reviewed by José García Escobar, Editor-at-Large, Guatemala.

Euridice is a passionate and talented girl, capable of musical virtuosity. However, despite her sister Guida’s intervention and Euridice’s obvious talent, her parents refuse to sign her up to the conservatoire in Praia Vermelha. They think she should be “playing with friends, meeting a boy, making a family.” Guida, impulsive and unlike her sister does not conform to having a domestic life and runs away with her boyfriend, Marcos.

Later Euridice is trapped in a dull marriage, painfully away from any creative endeavors. She tries cooking for a while, then sewing. Euridice quickly becomes a master chef and the most requested seamstress in town. However her husband Antenor consistently undermines her talents as well.

Euridice’s life as a mother of two and housewife is boring and meaningless. That is until her sister Guida triumphantly returns with her son, bringing with her a wonderful tale of life on the run: prostitutes, heaven, an orphanage—a tale reminiscent of Laila from JMG Le Clèzio’s The Gold Fish.

This duality balances each character’s extremes: coyness and rebelliousness, introversion and mutiny, quietness and adventure. But also, despite Euridice’s domestic nature, she’s far from one-dimensional; we get to see her revolt and create. And also, no matter how explosive and unpredictable Guida might be, we also have a glimpse of her fragility.

The author not only beautifully and meticulously explores the psychological diversity and personal history of Euridice and Guida, but of many of the characters around them. We meet and learn the history of the Gusmaos, the gossipy Zélia, Marcos, Antenor, etc. Part of the book’s charm is that the characters affect the course of the story directly. Either through their decisions or their inability to make them, The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao is inadvertently steered by courage, fear, and compassion.

This multigenerational epic takes us from Brazil in the 1940s to 1918 when the Spanish flu affected half of Rio, to the Gusmao’s household, and to the 1968 Brazilian coup d’état. Both epic and grandiose, The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao is also intimate and cozy, and let us not forget—funny, and witty, and inventive.

Through that personal and historical exploration, Martha’s writing comes out as whimsical and picaresque. The humor is part of the novel’s rhythm and musicality. The premise of a dull housewife may seem quotidian, but Martha Batalha’s humorous plot and writing turn that Kafkaesque everydayness into something almost Seinfeldian.

Humorous and sensitive, The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao is a warm exploration of family and circumstance. Despite its larger-than-life events, everyday life is what builds and sustains this novel. Euridice and Guida are two fascinating and memorable characters that carry the book with charm. Martha Batalha’s mature writing, which is also smooth and intoxicating, seasoned with characteristic authority and jolliness, and an immersive plot, makes this book a narrative delight.

It’s also worth-mentioning the work of Erick M. B. Becker, the translator, since he showed respect for novel’s language identity and its cultural personality.

The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao is not a linguistic pendulum, it doesn’t weave in and out of English and Portuguese, but Becker allowed for little details to survive the translation. We don’t see a Miss Ana, but a Dona Ana; we don’t see a Mister Manuel but a Senhor Manuel; we don’t see a do Mangue Avenue but an Avenida do Mangue; we don’t see a Gloria Hotel, but a Hotel Glória—accent and all.

Instead of looking for English equivalents, Becker allowed Martha’s Portuguese to walk freely, when needed. This includes accents, proper names, pet names, etc. Martha’s Portuguese—with its idiosyncrasies and particulars—in Becker’s hands survived the conversion and whitewashing translations sometimes have, and that’s always something to admire.

The Boathouse by Jon Fosse, translated from the Norwegian by May-Brit Akerholt, Dalkey Archive Press.

Reviewed by Norman Erikson Pasaribu, Editor-at-Large, Indonesia

The Boathouse is a traumatic novel. This is the second work of Fosse that I’ve read, after Aliss at the Fire, and both of them employ simple language but are overwhelming in terms of structure. In The Boathouse, single paragraphs can last more than ten pages, sometimes take a whole chapter, and the narrator uses repetition as a trope throughout the course of the novel.

This novel is deeply psychological, as I believe Fosse uses the repetitive style to mimic our fragmented thoughts. However, it’s exciting to note that we don’t actually read the narrator’s thoughts: it’s him writing about him writing. This structured reality and meta-fiction is significant for the book, as it introduces an element of self-censorship. It lets the narrator maintain the suspense and the mystery, leaving what would be more interesting if it stays unknown (like what happened to the narrator’s old friend’s wife or the narrator’s old crush) while maintaining its exasperating repetitive style.

The whole novel actually revolves around the jealousies the narrator harbours towards his old friend Knut: “Knut has become a music teacher, has got married, has a family.” The repetition of the texts above quite puzzles me, as it clearly shows that the narrator has an immense obsession towards Knut, which turn out later, strangely, not to be at all of an erotic nature. Textually, his obsession toward Knut was based on the fact that Knut left the band that they started together when they were younger. The narrator couldn’t move on with his life, while Knut now had a steady job and a life: a wife and two daughters. The novel becomes even more enticing when it breaks its creative wall—when the narrator starts fictionalizing Knut’s life, by continuing his writing with Knut’s point of view. And since the novel is the narrator’s writing, not the narrator’s actual thought, the reality in the novel is structured and chosen, be it intentionally or not. The narrator decides to make Knut jealous with the narrator’s closeness to Knut’s wife. Creative writing has been used by the narrator to be an act of revenge. This shows a deeper jealousy the narrator has toward Knut.

I also admire how subtle Fosse is at times, thanks to the graceful translation by May-Brit Akerholt. One good example is when the narrator gets into the boathouse again with Knut’s wife, where he usually played with Knut when they were kids, and the narrator thought, “I hear the waves, I hear the waves the way I heard them a long time ago.” It’s a simple line that skilfully portrays the tensions contained in the scene. We can see the narrator’s sentimentality in “a long time ago,” showing how he couldn’t move on from the past, his past with Knut, as he was being reminded of that past when he sneaked inside the boathouse years after their collision, with Knut’s wife. This part reminds me to a passage from Proust’s Swann’s Way, “Poets claim that we recapture for a moment the self that we were long ago when we enter some house or garden in which we used to live in our youth.” Perhaps that’s how the memories in this novel haunt its characters.

Read More Reviews: