This article by the prodigious French writer Marie Darrieussecq appeared in Le Monde des Livres on May 11, 2017. The occasion was the publication of the two-volume La Pléiade edition of the Complete Works of Georges Perec, who died thirty-five years ago, in 1982. It is a huge honor for a writer’s work to be published (usually posthumously) in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, which is a critical edition, with annotations, notes, manuscript and editorial variations, and accompanying documents. The books are pocket format, leather bound, with gold lettering on the spine and printed on bible paper. The series was begun in 1931 by the editor Jacques Schiffrin and was brought into the Gallimard publishing company in 1936 by André Gide.

—Penny Hueston

Georges Perec is now part of the Pléiade series. The novelty of the list of his titles being collected in this edition might have brought a smile to his face. He used to say, “Nothing in the world is unique enough not to be able to be part of a list.”

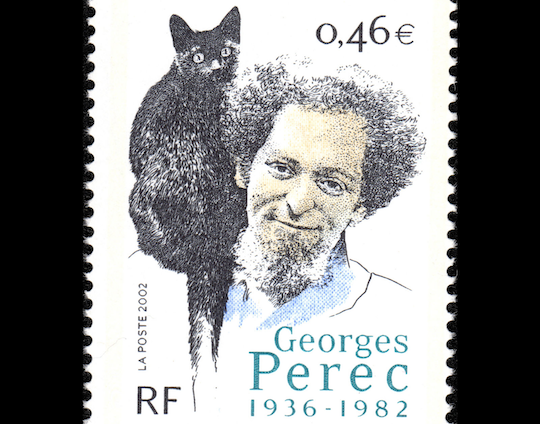

But Perec is unique. More than anyone else’s, his collected works resemble a UFO. He is a successor to Jules Verne and Herman Melville, to Stendhal and Queneau, to Poe and Borges, to Rabelais and Mallarmé…And yet Perec stands alone, bearded, playful, coiffed with a cat in his hair, like an icon in our popular imagination. And, although a dizzying number of references are woven through his work, his way of writing is freakily inventive.

His books were only intermittently successful in his lifetime, but after his premature death at the age of forty-six in 1982, his reputation grew exponentially. Perec quickly became the most recent of our classics. “A contemporary classic,” as the editor of this Pléiade edition of his Complete Works, Christelle Reggiani, writes in her preface, but an odd classic, both amusing and melancholic, whose humour shaped his despair.

His lipograms, constrained writing (the speciality of Oulipo, of which he was without doubt the most famous member), play around an absent centre, a missing letter, or an alphabetical prison house. His novel, A Void (1969), written without the letter “e,” is therefore written without them: without his father, who was killed in the war, without his mother, who was murdered in Auschwitz.

What seems to be Perec’s pleasant game with words is his way of saying the unsayable, of giving shape to absence, of proclaiming the abomination of the death of his mother and of the destruction of the Jews of Europe. He had what it takes to write that.

Along with Nathalie Sarraute, Perec is the one who managed to “implode” the autobiographical genre. “I have no childhood memories…” is the first sentence of W, or The Memory of Childhood (1975). In his autobiography he included doubt, ignorance, memory that can only imagine because there is nothing to remember, snippets or lists, and mountains of empty clothes. Instead of a story about self, we get absence, commonplace childhood memories that he does not have, the wax tablecloth, the table he sat at with his mother that was never cleared.

Perec wore his seriousness with a smile. In I was Born (1990) he wrote: “Not long before I was born, the Gentiles were not gentle.”

At first the critics were baffled by the apparent twists and turns in his style. They didn’t get it. He needed the ambition of a whole novel to offer the fullness of his art to the public. That was Life: A User’s Manual (1978), for which he won the Prix Médicis and recognition by a large readership. In this vast rooming house of a novel, Perec gathered up everything he cared for one way or another, his bits and pieces and his puzzles—somewhere between nothing and everything. The novel is a sort of saturated space of loan words and objects around a missing compartment and a booby-trapped heart.

Perec was beset by an impediment that could have been fatal for him. Obsessed by the need to write, he could have lost himself in endless repetitions, stylistic exercises and head-spinning flights of fancy. “Ah Moby Dick! Maudit Bic!”[1] exclaims one of the characters from A Void. The whale of the white page could have swallowed him up. The writing of W, or The Memory of Childhood took five years: “I can spend hours playing solitaire instead of writing.”

I admire his tenacity, and his “tricks” in the most noble sense: what he invented in order to make headway, despite everything. His barrages of constraints, his ultra-organised workspaces, his logs of technical specifications that were already books. He was a genius of a tinkerer.

He composed the crossword for the magazine Le Point and was hilarious and perverse. Take this definition: “especially fearful of certain whirling dervishes: circuit breaker.” Looked after by Françoise Dolto as a child, this survivor also wrote wonderfully about his analysis with J. B. Pontalis, in an essay called “The Scene of a Stratagem,” published in a posthumous collection of essays, Thoughts of Sorts. This short text is unfortunately not included in the Pléiade edition, which is primarily a collection of Perec’s published books. But perhaps there have to be a few missing compartments in a successful publication of Perec’s work.

Perec described himself as “a farmer who cultivates several different fields”: sociology, autobiography, playfulness, and the novel. “I simultaneously seek the eternal and the ephemeral,” he writes in his 1972 novella, The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex (in the collection Three), a tour de force verging on the unreadable, a verbal creation in which the letter “e” is the only vowel used.

In the illustrated Album Georges Perec, published alongside the two-volume Pléiade edition, Claude Burgelin describes a writer who interrogated the everyday by way of “dismantling the detective novel,” making methodical inventories and playing mind games. The typescripts and photographed manuscripts in this book of illustrations show how extremely organised Perec’s writing was, but also the times when things broke down, the boredom, the automatic drawings, the scribbles, the idle doodling.

This “user of space” (Perec’s description of himself) has an asteroid that bears his name: “2817 Perec,” discovered in 1982, the year of his death. Circling between Mars and Jupiter, its orbit has a semi-major axis of 2.35 astronomic units, an eccentricity of 0.179 and a gradient of 2.27 degrees in relation to the ecliptic.

Translated from the French by Penny Hueston.

[1] This translates roughly as “Ah Moby Dick! Moody Bic.”

Marie Darrieussecq was born in Bayonne in 1969. Her first novel, Pig Tales, was translated into thirty-five languages. She has written nearly twenty books. In 2013 she was awarded both the Prix Médicis and the Prix des Prix. She writes for Libération and Charlie Hebdo, and lives in Paris.

Penny Hueston’s most recent translation is Being Here Is Everything by Marie Darrieussecq, published by Semiotext(e) in the U.S. and first published as Being Here by Text Publishing in Australia and the UK.

*****

Read more about world literature: