The dissolution of authorship is intrinsic to the act of translation. Far from being mechanical vessels for the words of another, translators invariably leave a phantom imprint of themselves upon a piece of writing. They are the invisible co-authors of a text, the ghost writers who flit across linguistic frontiers, flirting with multiple literary identities. It seems unsurprising, then, that the most elusive of Portuguese modernist poets, the godfather of urban melancholia and man of many selves, Fernando Pessoa, should have worked as a translator for much of his life.

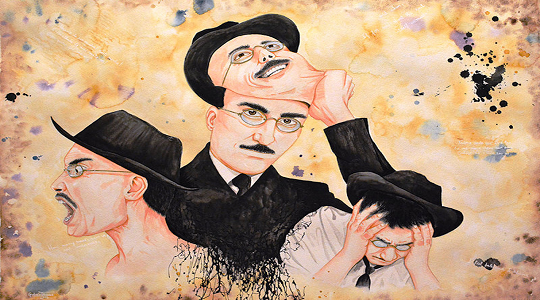

Pessoa’s writing spans countless styles and modes, but perhaps his most famous innovation lies in his use of ‘heteronyms,’ the multiple literary identities under which he wrote. Centred around the core triumvirate of Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos, Pessoa’s heteronyms continue to be discovered today, with over 130 currently known to us. Some of the heteronyms are even characterized by linguistic divisions, such as Alexander Search who wrote uniquely in English. As Pessoa scholar Darlene Sadlier points out, Pessoa’s splintering of authorship was in a sense symptomatic of the “general crisis of subjectivity in nineteenth and twentieth-century philosophy,” suggesting that the self is something to be created rather than preordained, and, therefore, that it can contain multitudes.

This summer has seen the publication of a new English edition of the work that brought Pessoa posthumous renown, the modernist masterpiece entitled The Book of Disquiet. The publication history of this work has become the stuff of legends. On his death in 1935 aged forty-seven, Pessoa left behind at least two large wooden trunks filled with thousands upon thousands of scribbled scraps of manuscript paper, a life’s work in fragmentary form. Out of these fragments, Pessoa’s project for a work called Livro do Desassossego (once translated as The Book of Disquietude, now as The Book of Disquiet) was discovered, but the “book” was found to have multiple authors, no discernible order, and was never completed. Here was the ultimate modernist text: a “deconstructed” book that could be infinitely reassembled out of thousands of scraps of paper lying in a trunk.

Given its chaotic and fragmentary nature, a Portuguese version of The Book of Disquiet was not published until 1982 following years of excavation and research, during which time scholars assembled the fragments and laboriously transcribed Pessoa’s near-illegible handwriting. The Book gradually emerged as a study in solitude, dreaming, creativity and alienation, a diary of sorts, an insomniac’s bible capable of moments of searing beauty, which purported to be the “autobiography of someone who never existed.” Bernardo Soares, the name under which much of The Book of Disquiet was written, was a Lisbon accounts clerk considered by Pessoa to be a personalidade literária (“literary personality”) rather than a heteronym in the strictest sense, but Pessoa also described Soares as “a simple mutilation of my personality. It’s me minus reason and affectivity.”

There have been at least four distinct English translations of The Book of Disquiet dating back to 1991, and many more editions have been published since. Each version has been forced to grapple with the ordering of the fragments, developing their own systems of categorization, chronology, and omission. The latest, expanded edition from Serpent’s Tail, The Book of Disquiet: The Complete Edition, takes the text originally translated by Margaret Jull Costa in 1991 and reorders it chronologically according to new scholarship by Jerónimo Pizarro, adding in previously missing material, as well as manuscript facsimiles, so that the book now runs to around 400 pages. There is, however, a certain hollowness to Serpent’s Tail’s claims of this being The Complete Edition. Given the fragmentary nature of the work and the endless possible configurations of the thousands of fragments, any attempt to create a definitive version of the Book seems to inevitably misunderstand Pessoa’s project, which remains monstrously, magically, incomplete.

That aside, this new edition goes beyond previous scholarship to offer a different approach to reading the Book. Editor Jerónimo Pizarro groups the fragments into two distinct “phases,” proposing that it be read in the order that it evolved, with the first writings dating back to 1913. Jull Costa’s translation is predictably seamless, and she has a deft touch in rendering Pessoa’s more lyrical passages in English: “the falling of leaves, measured and futile, like drops of alienation, in which the landscape becomes something for the ears alone, like a nostalgia for a remembered homeland.” This is haunting literature that sees Pessoa preoccupied by loneliness and apathy in the face of life. “I am offering you this book because I know it to be both beautiful and useless (…) I put my whole soul into its making, but I wasn’t thinking of that at the time, only of my sad self and of you, who are no one.” The Book’s extraordinary appeal lies in the universality of Pessoa’s address; he writes to everyone and no one.

A translation will always be, in some sense, a destruction of the “I.” The original text must be boiled down to its constituent parts and lovingly re-moulded into new forms, just as the original author must cede ground to the translator. There is thus no single author of this version of The Book of Disquiet, which is in truth a palimpsest of the various voices of narrator Bernardo Soares, writer Fernando Pessoa, translator Margaret Jull Costa, and editor Jerónimo Pizarro, giving rise to a rich and unique configuration of the “book.” To borrow the words of Mexican poet Octavio Paz in his essay on Pessoa: “The destruction of the I (…) provokes a secret fecundity. The real desert is the I, not only because it locks us up in ourselves, and thus condemns us to live with phantoms, but because it withers all that it touches.”

Laura Garmeson is Asymptote‘s Chief Copy Editor.

*****

Read more essays and reviews: