Across the China Sea explores an unconventional family in rural Norway coming together during the weakening German occupation of the country. A review by Asymptote Assistant Managing Editor Sam Carter.

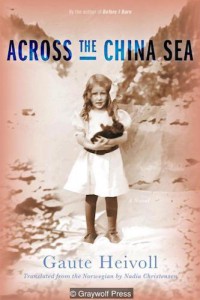

It begins with the discovery of a contract, but Gaute Heivoll’s Across the China Sea, translated by Nadia Christensen, is ultimately the story of a community that generously insists on inclusion over exclusion. First published in Norwegian in 2013 and recently released by Graywolf in Nadia Christensen’s consistently elegant translation, this novel is Heivoll’s second to appear in English after Before I Burn, a partly autobiographical work that explores an incident of arson. In Across the China Sea, however, loss assumes a rather different form—one less concerned with spectacle and more attuned to the small gestures that often make all the difference.

A young family moves from Oslo to a small town near the coast in order to start anew. They’ve come not to flee the city but to build a better version of something they already understand: an asylum. The parents—both of whom are trained nurses—decide their newly-built house can accommodate more than just biological children. Soon afterward, in addition to caring for three grown men, they take in five siblings the state had taken away from mentally unfit parents. At this new home, the children, who are also variously disabled, live in a fully furnished attic, yet they’re hardly out of sight or mind. They begin to interact with other members of this curious collective, including the narrator and his younger sister—the only two members of the household biologically linked to the nurses.

Bonds, in other words, are not limited by blood, and an early tragedy not only puts that belief to the test but also brings into sharper relief the contours of this unusual community nestled into the Norwegian countryside. Any separation between the groups of children is rendered meaningless at a time when comfort cannot be sought selectively. Indeed, the delicate balance proves resilient enough to deal with another loss that, while only temporary, still takes an emotional toll. Patients and patience quickly become intimately intertwined, exhibiting a link that their etymological affinity can only begin to capture.

Heivoll deftly explores the subtle dramatic possibilities of this tangled web of interactions among a family, the people they care for, and the state that was initially responsible for bringing them all together. During the fifty-year period covered by the narrator’s recollections, characters drift apart to reveal how the mentally disabled children experience family in a number of forms: first with the inadequate care provided by their biological parents, then through the guidance of trained nurses who work in their own home, and finally in a facility administered entirely by the government. Crucially, however, the five siblings also remain together for much of this time, marking out a different sort of caring core—what the narrator describes, at one point, as “almost an ordinary family.” Yet, as the novel emphasizes time and again, no group is ultimately better than any other—the simple act of association or gesture of generosity counts more than anything else.

(Graywolf Press, 2017)

That same generosity extends to the way Heivoll takes great care to avoid one of the problems that tend to befall writers depicting disabled characters: making them simple, saint-like figures or finding similar ways to make their actions or motivations instantly transparent. Rather than leaving them too legible or predictable—and thereby robbing them of any subjectivity—he allows the siblings to maintain some semblance of privacy, of opaqueness. It’s a sensitive approach, but one might expect nothing less from a novelist who, like Heivoll, has studied psychology.

Heivoll displays similarly wise restraint elsewhere when refraining from any attempt to turn the caretakers into heroes. The mother finds it hard to confront her feelings in a place where she must constantly tend to those of others while the narrator reacts as a young boy often unfortunately does when encountering difference—with a provocation or taunt that masks the struggle to understand. The father, rather than taking any dramatic stance to defend his charges, must drown his frustration with the way others refer to them as animals through long, solitary walks in the rain. A simple decency rather than any extraordinary effort characterizes the actions of many of those involved.

Comparisons to Karl Ove Knausgaard might be inescapable for another Norwegian writer—particularly since Heivoll’s novel, like the first volume of My Struggle, revolves around the clearing out of a parent’s home—but it’s worth stressing that the Across the China Sea breathes some much-needed air into the relentlessly solipsistic and occasionally claustrophobic perspective of the former. Even when Heivoll includes some breathless passages about Nordic living that make Scandinavian simplicity eminently enviable, there’s always a return to some reference to the collective effort it often requires. In other words, the novel can be as consistently centripetal as Knausgaard’s, but here the center is a “we,” not so much an “I.”

The title, whose meaning becomes clear early on, alludes to the refashioning of an object that had long ago traversed that body of water. The story of that recycling process is, in turn, repurposed by the narrator as a soothing tale for a young and anxious listener, and this arc from material to myth subtly reminds readers of not only the workings of a novel but also the ways in which a new context can disclose new or unexpected possibilities. The key, of course, is remaining open to discovering them, and Heivoll’s novel makes the powerful case that communities tend to provide it far more frequently than contracts.

Sam Carter is an Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more reviews: