Diverse languages and artistic disciplines intersected at the Youmein Festival in Tangier where artists and writers from Morocco, Algeria, Spain, and France created pieces to reflect the interplay between tradition(s), taqalid, تقاليد, and imitation, taqlid, تقليد.. Asymptote’s Tunisia Editor-at-Large Jessie Stoolman and writer Alexander Jusdanis report from Tangier.

For the past three years, Youmein (“Two Days” in Arabic) has brought together diverse artists in the city of Tangier to create art installations based on a central theme over a 48-hour period.

The festival is run by Zakaria Alilech, a translator and cultural events coordinator at the American Language Center (ALC) Tangier, George Bajalia, a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at Columbia University, and Tom Casserly, a production manager at Barbara Whitman Productions. They’re quick to emphasize their hands-off approach. “We’re not curators,” says Alilech. Instead, they see themselves as facilitators, providing artists the initial inspiration, space and support to realize their ideas. The trio stressed that Youmein is less about the final product and more about the process of making art.

They intend the festival to be an opportunity for the artists and audience to discover Tangier through the lens of each year’s theme. While strolling through the city’s streets, historically a meeting point for peoples from around the Mediterranean and beyond, it is not uncommon to hear any combination of Rifiya, Darija, Spanish, French, English, and Italian. Thus, it is perhaps unsurprising that language has played an essential role in selecting the theme of the Youmein festival from its inception.

Youmein’s first edition explored barzakh, a word from Classical or Modern Standard Arabic, used in Darija. Barzakh an Islamic border space that can refer to the space between life and death as well as the point where fresh and salt water meet. The theme emerged after a conversation between Alilech and Bejalia about how to translate barzakh, which has taken on new meaning within the context of trans-Mediterranean migration. Since the Straights of Gibraltar are sometimes referred to as barzakh, some within the migrant communities passing through Morocco have developed new expressions for describing their experience as je fait le barzakh or Barca ou barzakh, adding further layers of meaning to the already nuanced term.

This year’s theme was imitation, particularly focusing upon the close relationship between taqlid (تقليد), the Arabic word for “imitation,” and taqalid (تقاليد.), the Arabic word for “tradition.” Although in Classical or Modern Standard Arabic, taqlid implies both “imitation” as well as “tradition,” (singular), in Darija usage taqlid only refers to “imitation,” and taqalid only denotes “tradition(s).” Despite the morphological closeness, Alilech noted that for many Moroccan artists imitation is often used to denote “anti-tradition,” or the copying of the Western world. In Tangier, often seen as a “contact zone” between Morocco and Spain, and more broadly between Africa, Europe, and the Arab World, this anxiety of influence often ends up creeping into artistic production.

It’s in the tension between taqlid and taqalid that Youmein’s organizers felt artists could find a “productive capacity” to work through in their pieces. “How do cultures change?” they asked in the call for proposals. “Is a society made up of endless imitations that become canonized as tradition? Or do traditions change through borrowing from other cultures and societies?”

In an attempt to equalize the power dynamics engendered by Morocco’s multifarious linguistic environment, Youmein’s organizers accepted proposals for the festival in three languages: English, Arabic, and French. Additionally, all the activities involving the artists—the initial meeting, studio time, and exhibition—were conducted in the language most preferred by the artist, be it Moroccan Darija, Algerian Darija, French, Spanish, or English, with translators always available.

Nonetheless, with much funding and support for the event coming from American organizations (both governmental and non-governmental), there was a certain pull to use English at some of the public events, including the roundtable discussion held the first day of the festival at the Tangier-American Legation, where Noha Ben Yebdri, founder of Mahal Art Space in Tangier, and Carlos Perez Marín, professor of architecture at the Ecole Nationale d’Architecture de Tétouan, discussed the history of contemporary art in Morocco.

Despite the tendency towards French and/or English at the discussion, Darija, the language probably most widely accessible for residents of Tangier, was always represented in the festival’s other events, from the open studio hours to the exhibition. Additionally, in the two pieces that were explicitly multilingual, Darija was the dominant language used.

Following the roundtable discussion on July 28, the fifteen artists got to work. While previous editions had spread the festival across different art spaces throughout the city, this year the organizers decided to place all the artists in one room: the basement of Tangier’s TechnoPark, which is apparently set to be renovated into a theater for the local group Daba Theatre. For now, the space is, appropriately, a work in progress: a dark, dusty, concrete playground, complete with irregularly spaced columns, angular corridors, and the occasional stack of bricks. Making their nests in the basement’s nooks and corners, the artists worked in close proximity, temporarily becoming a “family,” in the words of one. Many contrasted the space favorably to a typical art gallery—white, clean, well lit, everything in its right place—which might be why Alilech said Youmein feels particularly “human.”

In contrast to the roundtable, the exhibition attracted a diverse crowd. The theater space, which could reasonably fit at least 100 audience members, was comfortably packed with mostly young twenty-somethings, many of whom were neither involved directly in Tangier’s art scene nor in the activities of the American Language Center/The Tangier-American Legation.

The push to provide a space accessible for artists and attendees with differing experience and linguistic backgrounds is a reflection of the festival’s commitment to reflect trends in the art and literary scene within Tangier. Rather than imposing Anglo-European artistic and linguistic norms, Youmein adapts to the reality on the ground in hopes of creating a space “where no one feels like they are not the intended audience,” in the words of the organizers.

Works exhibited

Adam Raougi

Adam Raougi, a guitarist and one half of the R&B duo West 7olm, learned R&B guitar from his father. A few months before Youmein, he became interested in chaabi music, a pulse-driving mix of Moroccan traditional styles usually played through the night at weddings. For Youmein, Raougi attempted to bring the softer, darker emotional palette of R&B to chaabi’s multi-layered, incessantly happy beat, making a loop of the basic tamborine and darbouka patterns with a melancholy chord progression and then performing a blues solo on top.

Lotfi Souidi

In the middle of the room, the Arabic words for peace (salam), love (hub), and tolerance (tasamuh) are cut into metal with propane tank flames burning from the words’ contours. The fire could suggest a kind of violence enacted on the words, but gently burning and floating in the air, the set-up feels delicately balanced instead.

Souidi, is a multidisciplinary installation artist based in Tetouan, said he took “imitation” as the process, rather than the result. His work for Youmein represents a new project taking everyday objects and transforming them. The propane tank is a ubiquitous feature of most Moroccan homes. “Everybody understands its use,” he says. So what happens when it’s used to send love, peace, and tolerance up in flames?

Oussama Tabti

Visual artist Oussama Tabti set out a series of six postcards for the taking, each with a photograph of a Moroccan cellphone tower disguised as a palm tree. The cellphone towers are ubiquitous throughout the country. When pointed out, the deception is obvious. But if you’re not looking for the towers, they’re almost invisible.

These bad copies are banal, sinister, and hilarious. Tabti has said that the photos were intended to show the “artificial side” of Marrakech. “A little showcase where [the city] is what is expected of it: a little ‘Oriental fantasy’ for many Western tourists. This is how the idea of the postcard stand was born, reinforcing the notion of utopia, a well-framed image that we want to attribute to a particular city or country.”

Lena Krause and Ramia Beladel

Ramia Beladel and Lena Krause worked together on “Waiting for Godot/Monika,” where they addressed both the imitation and tradition question using elements of visual, performance, and theatrical art. Expanding on a personal project documenting the mannequins (or monikas, a word also used in Darija for “doll”) found in markets throughout Morocco, Krause covered headless, nude mannequins with responses from observers and participants in Youmein to the question “Do you fit with the roles you see in your society or defy them?” / “ولا كتعارض مع الأدوار لي كتعطيها المجتع ديالك؟ واش كتفق”

Responses included:

“I am the oldest one so I should take care of them.”

“I LEFT SCHOOL AND MY DREAMS TOO.”

“ما كيحشومش قالك “هادي إميتاسيون واعرة” فحال دوريجين” / “They have no shame…they say ‘this imitation is amazing’ just like the original.”

Ramia Beladel, contributing to her lifelong work in conversation with Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, displayed balloons in various stages of inflation, each with a rock inside, which were then mounted and painted white. Underneath the first one it read “I am,” the second “a wasted breath,” and the third, “inside a balloon.” For her, the use of the rock comes from participation and observation in Sufi activities, where the individual’s interaction with nature is a focal point for meditation.

When asked about how their projects interact, Ramia explained: “The collaboration is imitation. She imitates me and I imitate her. Stereotype comes first, imitation comes second, and tradition comes third. Local imitation for us is tradition. Stereotype engenders imitation.”

Maya Benchikh El Fegoun

Maya Benchikh El Fegoun’s piece “L’awziya” put imitation in conversation with tradition by visually interpreting “l’awziya,” or “the distribution,” a ritual practiced by certain Amazigh tribes (native inhabitants of regions throughout North Africa) in Algeria. At “l’awziya” members of the tribes gather to discuss communal issues and a male cow is sacrificed. Each family receives an equal portion of the sacrificed cow. El Fegoun mentioned that this practice was stopped in the nineties and has only recently resurged. When discussing her piece’s interaction with the theme, the hypothetical question was posed “quelle est le sante du partage? / how does it feel to share?”

Ahmed Benattia, Carlos Alcántar, Alaeddine Lazaar, and Nadia El Kastawi

In a cramped corner space of the theater, crowds gathered to watch the only theatrical piece at the festival, which was written, produced, and performed by actors Carlos Alcántara, Ahmed Benattia, Nadia El Kastawi, and Alaeddine Lazaar. Through the creation of three archetypical characters (representing a young Moroccan man, a young Spanish man, and a young Spanish woman), the piece addresses the role imitation and tradition play in shaping views on sex and love. Borrowing from popular music and canonical literary texts, mainly composed of interrelated monologues from the two male characters, with occasional dialogic interventions from the female character, and an overarching narration, the audience witnesses the two protagonists’ personal struggles against societal pressures and injustice. This was one of two multilingual pieces at the festival, as Alcántar spoke in Spanish, Lazaar in Darija, with narration from Benattia in Spanish, French, and Classical Arabic.

In a separate piece, Carlos Alcantara also produced short, free verse poems in English that address how imitation and tradition inform poetic practice.

M’hammed Kilito

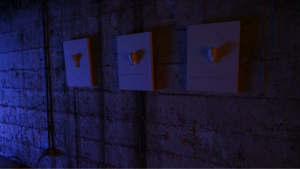

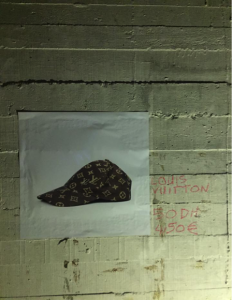

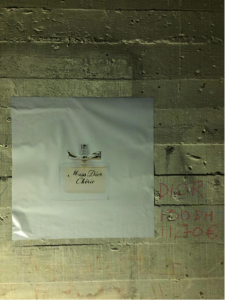

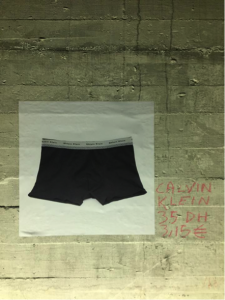

Photographer M’hammed Kilito’s piece “Mitation” explores the boundaries of imitation and tradition through reproductions of reproductions. Using the standard photography style employed in mass-consumer advertising, Kilito photographed different clothing items from markets in Morocco that sell off-brand reproductions, with names such as “Ghlvan Klein” and “Miss Dior Chérie.” The photographs were hung with the official brand name and market price for the knock-off item (in Dirhams and Euros) written next to each in red, allowing the audience to determine where the boundary lies between real and fake.

Nina Cholet and Boris Carré

Dancer Nina Cholet and video artist Boris Carré collaborated on a performance by Cholet, accompanied by a projections of herself and a second dancer. Throughout the piece, Cholet closely mimics the body language of the projected dancer and of herself, as the projections flicker, delay, and become overlaid. The performance stole the attention of practically all in attendance, leaving the room in silence, except for the sound of Cholet’s breath. While Cholet demonstrated her mastery of bodily imitation, the piece suggested the futility of making a perfect copy. Instead, hints of the potential for new creation emerged from the slight discrepancies between the projected and physical bodies. The piece recalled a line from “The Aleph” by Jorge Luis Borges: “I saw all the mirrors on Earth, but none of them reflected me.”

Mehdi Djelil

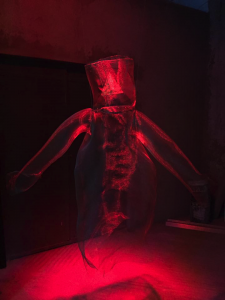

At the entrance of the show, attendants were greeted by a hanging, oversized torso made of wire, with a North African men’s wedding hat fit inside. Mehdi Djelil, a multidisciplinary artist from Algeria, explained that the piece is the beginning of a longer-term project inspired by a trip around Tlemcen, a city in northwestern Algeria near the Moroccan border. The wire figure is an almost-empty form for a man’s wedding clothes. In a way it feels naked, like an invitation for the viewer to try dressing it in different outfits, variations on the same basic shape. If freedom comes from constraint, then the wire is a cage.

Alexander Jusdanis is an editor and writer living in Rabat, Morocco. His writing has appeared in Reorient and Muftah, and he tweets as @xanijusdani.

Jessie Stoolman is Editor-at-Large, Tunisia at Asymptote. She currently works as a librarian in Sousse, Tunisia and intermittently contributes to transnational research projects, when possible.

*****

Read more dispatches: