Today, we continue our spotlight on the winners of Asymptote’s annual Close Approximations translation contest, now into its 3rd edition. (Find the official results and citations by judges David Bellos and Sawako Nakayasu here.) From 215 fiction and 128 poetry submissions, these six best emerging translators were awarded 3,000USD in prize money, in addition to publication in our Summer 2017 edition. After our podcast interview with Suchitra Ramachandran, we are thrilled to bring you fiction runner-up Brian Bergstrom in conversation with Asymptote Assistant Interviews Editor, Claire Jacobson.

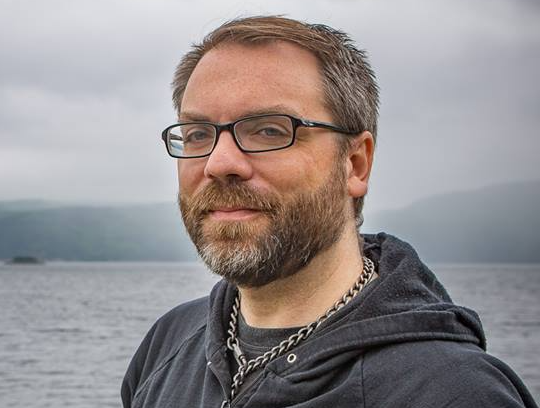

Brian Bergstrom is a lecturer in the East Asian Studies Department at McGill University in Montréal. His articles and translations have appeared in publications including Granta, Aperture, Mechademia, positions: asia critique, and Japan Forum. He is the editor and principal translator of We, the Children of Cats by Tomoyuki Hoshino (PM Press), which was longlisted for the 2013 Best Translated Book Award.

His translation of “See” by Erika Kobayashi from the Japanese was a runner-up in Asymptote’s Close Approximations contest. This is what fiction judge David Bellos had to say about it: “Erika Kobayashi’s ‘See’ earns its place as a runner up by imagining a world just like ours save for a craze for a pill called ‘See’ that induces temporary blindness. People take it so as to go out on blind dates and drives to the sea. Read on! The English of the translation by Brian Bergstrom seems to me flawless.”

Claire Jacobson (CJ): I really enjoyed reading your translation of Erika Kobayashi’s story “See” in Asymptote’s most recent issue, and I was struck over and over by the temporal fluidity and ambiguity of the piece, and how challenging that must have been to translate. How did you make your decisions regarding difficulties of tense, and what are some of the other Japanese/English grammatical difficulties?

Brian Bergstrom (BB): Standard prose in Japanese has slightly different conventions than in English regarding tense—something set in the narrative past can be written so that even as key sentences employ unambiguously past tense verbs, many others are written in present tense. Usually, this can all be converted unproblematically into consistent past tense in English. But in this story, Kobayashi is taking advantage of this quirk in Japanese to create a zone of ambiguity—there is an overlap of past events and present ones that also blurs the lines between two characters who seem to be experiencing similar things at different times; the grammar creates a space that allows them to become each other. I ended up employing the present tense more often than usual in English to create this sense of suspended or ambiguous intersubjective temporality, whereby past experience and present experience can be told in a way that is “co-present,” if you will. The sense of immediacy so created allows for the empathetic union of mother and daughter around which the story revolves.

The other main translation challenge had to do with the identification of characters principally by their relations—there are names, but most often characters are referred to by their relation to the deceased mother: her older daughter, her younger daughter, etc. This sounds awkward/confusing in English a bit more than it does in Japanese, as there are specific nouns denoting these relations that can function quite cleanly as “names” of a sort; it’s wordier in English. I don’t think I was able to overcome all the awkwardness in English, but I worked to make it flow as clearly as possible while retaining the emphasis on identity-as-relation; hopefully the awkwardness at certain points can be a kind of pleasure in the text, rather than a flaw.

CJ: How did you decide to translate this text in particular, and did you have the chance to work with Ms. Kobayashi during your translation process?

BB: I have been working with Kobayashi for the past few years, ever since I attended a conference on nuclear issues at Université de Montréal where she was invited to speak about her writing and art. I have had the privilege of working with her on English dialogue for her manga, Luminous, as well as translating a short prose piece she presented as part of a recent art installation. I am currently working on a translation of her novel, Breakfast with Madame Curie, and while doing this, I naturally have been keeping up with her publications—this story came out last spring in the journal Waseda Bungaku, and I found it so striking, primarily because of the overall feeling of the language. In Japanese, there is the term 透明感 (tōmeikan), which literally means a feeling of “transparency” or “clarity.” I don’t like to evoke Japanese words talismanically, as if there’s some unbridgeable gap in sensibility between Japan and the rest of the world, but in this case the English words “transparency” or even “clarity” don’t quite capture what tōmeikan indicates—it’s a feeling paradoxically both soft and crystalline, like translucent white cloth shot through with sunlight. It’s frequently used to describe a certain quality of voice, and the language of this story evoked this feeling in me as I read it. One of my main objectives when translating it was to see if I could evoke a similar feeling in English.

Because of our ongoing professional relationship, I am in regular contact with Kobayashi, but I did not consult her during the translation process. Instead, I honed it as much as I could and then showed her a complete draft. Since she has lived and worked in New York, she has a good knowledge of English, and I make it a practice to show her my translations to solicit her opinion. She suggested no particular edits for this piece, however, and instead encouraged me help it find an Anglophone readership. We’re both overjoyed that Asymptote is allowing that to happen!

CJ: In this text, the language and content seem to interact to create the feeling of generational perpetuity—who is whose daughter or mother, and who is learning from or talking to whom. How were you able to navigate that dynamic in the translation, and did you ever feel the need to clarify or expand on what was already there?

BB: It’s an important impulse to “nail down” the denotations and connotations of the work you’re translating, to follow to their logical conclusion everything implied in a text so that your recreation of it is as precise as possible. It is in this sense that a translator has to be a kind of ultimate close reader. But in this story, Kobayashi intentionally uses the literary capacity to articulate ambiguity for thematic reasons—the inability to precisely answer, in the end, the question of who is who and at what precise point mother and daughter blur into each other and switch places: this is the very point of the story. So, I had to be precise about how to re-present this imprecision and resist the impulse to over-explain or clarify. Kobayashi talks about this story as a way for her to come to grips with realizing that she only knew her mother as her mother—not as the woman she was before she had a daughter—and that she wrote and published this story while pregnant; in other words, Kobayashi wrote this story while contemplating the imminent arrival of someone for whom she herself would be similarly unknowable outside the category of “mother.” So, the indistinguishability between mother and daughter in the story expresses both that commonality in experience and the essential unknowability—the blindness—lying at its heart.

CJ: Just out of curiosity…is the wordplay with “sea” and “see” (and the irony of the drug’s name) present in the same way in Japanese, or did you have to come up with an approximate alternative?

BB: In the Japanese text, the name of the drug is spelled out in Roman letters (SEE), and the observation about the irony of the name is spelled out the same way as it is in the translation. At one point, when the sisters are playing their “Helen Keller” game, the word “sea” is spelled out in Roman letters as well—the English word is being drawn letter-by-letter in that sequence, rather than the Japanese word. So, the see/sea connection is present in the story even in the original. But throughout the story, the word I’ve translated as “sea” is the Japanese word 海, which is pronounced “umi” and can also be translated as “ocean”; the verbs for “to see” in the story are not phonetically or orthographically similar to that word, meaning that there is no wordplay in the Japanese at that level. This means that my translation, because it is in English, plays on that connection more explicitly than the Japanese, and one of my worries as a translator was not to overdo it—not to let it become too precious or clever-clever. But I also wanted to allow English to speak to the reader as English (and as literature written in English) even as it is based in Japanese, just as the Japanese speaks as Japanese and as literature written in Japanese while also alluding to English. The sea/see connection has literary resonances with Virginia Woolf and Iris Murdoch that seemed important to allow to come to the surface in English, and in this way, I felt that my translation could be a creative act while still remaining true to the original—or rather, be a creative act in order to remain true to the original.

CJ: What significance does the use of English for this purpose carry for the Japanese reader? What is the effect of this borrowing in the original, and is there any way to replicate that in a translation?

BB: This is actually a difficult question, I think—but of course, interesting.

For one thing, English is of course a hegemonic language in Japan, just as it is worldwide. For example, another writer I translate for, Tomoyuki Hoshino, deliberately uses Latin America and the Spanish language literary heritage as the “foreign” element in his Japanese-language work, and insists on Spanish rather than English/Euro-America as his reference, not only because he lived there and is personally invested in the culture, but also for political reasons—to break up the “default” of English as hegemonic foreign language in Japan.

Kobayashi is not quite in that position, and she has lived and worked in the U.S. as an artist. When she uses English in her work, as in “See,” I think it works texturally and at a “pop” level—the use of brand names, especially that incorporate simple English words, is very common in Japan. In a way, it’s simply natural that the brand name of the drug in the story would be in English, and a word that simple would be familiar to a Japanese audience. The name of the story, after all, is not a Japanese word that means “see,” but rather the word “see” transcribed into katakana (シー: “shii“), the script used for words experienced primarily phonetically, like foreign words. If you look at the original in Japanese, you’ll see that occasionally a word will have a hypertext link to a phonetic spelling-out of certain words, including “SEE” when it is written in Roman letters in the body of the story. In standard print, these are not hyperlinked, obviously, but rather written in a superscript over the top of them that’s called “rubi“—itself an adaptation of the English printer’s term “ruby,” used for the size of type in interlinear notation. In this story, rubi is used to clarify the pronunciation of the two proper names in the story (Sadako and Riko) and the drug name “SEE,” which is only spelled phonetically—not in Roman letters—in the title.

I’m belaboring this point because I think the choice to title the story with the phonetic transcription rather than the Roman letter spelling is deliberate, and sets the stage for the sea/see wordplay that occurs when the sisters are playing the “Helen Keller” game. The movie, The Miracle Worker (1962), incidentally, was and continues to be quite popular in Japan, and so it’s relatively natural to have that reference in the story; similarly, Japanese children take English classes from a young age as part of standard education, so a children’s game spelling out simple English words is not far-fetched either. The phonetic transcription of the term for the title allows the “SEE” of the drug name and the “sea” in the children’s game to come together and sort of hang over the story, reminding readers of these English words that they almost certainly encountered during their primary education, as well as their phonetic proximity, even as the rest of the story uses standard Japanese words to indicate those concepts.

Some people have asserted that authors like Haruki Murakami or Banana Yoshimoto write prose that is “just like” English and therefore not good Japanese prose, or not “really” Japanese prose; in part, this is chalked up to the so-called influence of English on these writers and on the tastes of the Japanese readers who made them so popular even before they became internationally famous in English translation. I don’t subscribe to that view, though, and I think it flattens the literary possibilities of playing on the English that has been adapted into Japanese into a simplistic dualism, when in fact, it’s a complex interplay that opens up Japanese literature to the (English-dominated) world but also allows that world to be affected directly by Japanese literature. I think Kobayashi very cannily sounds this English-derived chord within Japanese and lets it resonate throughout the piece and bring it together at that level.

Claire Jacobson is the Assistant Interviews Editor at Asymptote. She studies French literature at the University of Iowa, and translates from French and Arabic.

*****

We’re currently raising funds for the next edition of our annual translation contest. If you’ve enjoyed this showcase and would like to support us in our mission to advocate for emerging translators from underrepresented languages, consider a one-time tax-deductible donation (for Americans) or join us as a sustaining member today!

*****

Read more interviews with translators:

- In Conversation: Carol Apollonio on Serving the Spirit of Communication in Translation

- In Conversation with Iranian-American poet and translator Kaveh Akbar

- In Conversation: Lesley Saunders on translation, poetic collaboration and creating new writing with refugees