During the past thirty years indigenous literatures in Spanish and indigenous languages have slowly emerged onto the literary scenes of many Latin American countries. Despite what many refer to as a literary renaissance, these literatures garner scant attention beyond the region, and many masterworks of contemporary indigenous letters remain unavailable in English translation. A graduate student at the University of California-Davis, Sean Sell recently published an excellent translation of Maya literature from the Mexican state of Chiapas with the University of Oklahoma Press. We caught up with Sell to discuss his work, that of the authors he translates, and his role as a conduit of indigenous writing in English.

Paul Worley & Kelsey Woodburn (W&W): What led you to an interest in Mayan languages and literatures?

Sean Sell (SS): Credit the Zapatistas, I suppose. Their uprising captured my attention as it did with so many others, so in 2000 when I was looking to visit Mexico and work on my Spanish, I got involved with the organization Escuelas para Chiapas or Schools for Chiapas. I figured I could improve my Spanish and support this intriguing project at the same time. Schools for Chiapas is based, at least on this side of the border, in San Diego, where I’ve lived most of my life. They regularly organize trips to Zapatista territory. Our group helped prepare a site for school construction in one of the communities. But the trips are as much about cultural exchange as they are about any particular project.

It was on this trip that I first learned of indigenous languages like Tsotsil and Tseltal. Organizers told us that many of the Zapatistas we would meet did not speak Spanish, and for those who did it was probably their second language.

Years later I was getting a master’s at San Diego State University, and I took a class called Mexican Sociolinguistics. I thought it would be about Mexican variations and regionalisms in Spanish, but it was all about indigenous languages—their history, their variety, their different levels of health today. Estimates of how many indigenous languages remain in Mexico range from 68 (the number with government recognition) to almost 300, with some disagreement as to when languages are distinct rather than different dialects of the same one. It was fascinating to learn about this, as each language represents a particular cultural world. I drew from my experience in Chiapas for the class.

At the same time I was taking a Chicano literature class, and it struck me that in the U.S. Spanish was the oppressed minority language, while in Mexico Spanish was the dominant, colonial language oppressing the indigenous ones. I decided to explore that for my master’s thesis, focusing specifically on Chiapas since I had experience there. And so I read all the literature I could get my hands on by indigenous Chiapas authors. I think it’s fair to say that 50 years ago that would have been nothing. This was about seven years ago, and I was able to find a good number of collections of folk stories, but not much beyond that.

In articles or books about Chiapas I found frequent reference to a burgeoning contemporary literary scene, going along with an overall sort of cultural awakening that also includes music, art and performance. I even found websites showing images of some books, but I couldn’t order them from the U.S. It seemed to me someone should go down there and work on translating and seeking publication for these books in the U.S., in English. So after I finished my master’s program, that’s what I did.

W&W: You mentioned an ‘overall sort of cultural awakening’ could you expand a little further on what you mean by this? How is the cultural awakening effecting music and art of the area as well?

SS: In music, you’re seeing groups incorporate indigenous styles and themes into music that also features contemporary rock, pop, or hip-hop aspects. The group Sak Tzevul is probably the best known.

CELALI, the State Center for Indigenous Languages, Art and Literature—that’s the organization that published the book I would go on to translate—in addition to publishing hundreds of books, they also promote art and music. My co-editor Nicolás Huet Bautista is one of the founding members. You can see some information on their website. They’ve had workshops and courses for writers, and that helped promote the writers in the book.

Galeria MUY is another exciting place in San Cristóbal where they display indigenous artwork and have poetry gatherings to promote indigenous poets.

Now, I don’t have a long history with San Cristóbal, but those who do tell me the city’s identity has changed dramatically in recent decades. It used to be a city of mainstream Mexicans, which indigenous people would visit at their own risk. Nicolás Huet wrote a story, “Paso a paso” [“Step by Step”] about a family making the journey. It doesn’t go well. Diane Rus, an anthropologist who, along with her husband Jan, has worked with Tsotsil people for years, says that in the past, if she wore a Tsotsil style piece of clothing like a huipil, San Cristóbal residents would make whistling or hissing noises to show their disapproval of her sympathies with the indigenous.

Today the city has a proud indigenous identity. The indigenous open-air market is part of the town’s cultural center, stores feature indigenous clothing, accessories and artwork, language schools offer classes in Tsotsil and Tseltal. I certainly don’t want to paint too rosy a picture—there’s a great deal of unrest and conflict, and indigenous people are still marginalized in many ways (having products for sale doesn’t mean having a say in the government), but Chiapas’s indigenous people are actively taking roles in social movement.

W&W: You also mentioned working on translation and seeking publication in the U.S. How do you approach getting translation projects approved and what is the process of getting published? Is it hard to keep both author and publisher happy?

SS: The best answer I can give is, keep trying, keep asking until somebody says yes. As an advisor here at UC Davis says, expect to be rejected. Everybody in academia is rejected a lot, so we have to see that as part of the process, but acceptances will come.

As to keeping author and publisher happy, on the one hand that wasn’t too difficult because all parties were cooperative and understanding in this case. My editors at OU Press appreciated that I could consult with authors if necessary, and the authors appreciated the ability to clarify questions. But it was sometimes a challenge—conversations could take awhile, as I’d have to wait for emails to come from Oklahoma or Chiapas when I was in California. It was nice that I could go back to Chiapas last summer and meet with authors in person to review different matters.

W&W: Not many people know that Maya literatures or even in general indigenous literatures exist. Why do you think that is? What is the role of the translation in the promotion of these literatures even within their countries of origin?

SS: Indigenous people have been made invisible and otherwise dehumanized for centuries, in many ways. One aspect, which we address on the book’s back cover, is that in Mexico many Spanish-speaking people refer to Indian speech with the term dialecto, and not in its proper meaning as a regional variation of a language, but as if it refers to something less, something closer to animal noises and not a full language. Believe me, in my efforts to learn Tsotsil, I’ve found it to be highly sophisticated, with complex rules of grammar and syntax.

Colonialism in the new world has not ended; rather, the colonizers took control away from European nations. Indigenous people throughout North and South America continue to fight to preserve their culture and have at least some control over their lives. Words like autonomy, sovereignty, and agency all relate to this struggle. While Western Civilization may see the world as a set of nations based on lines drawn hundreds of years ago by white politicians and map-makers, indigenous people (those who haven’t been displaced) have older connections to lands based on where and how their cultures developed. These writers use literature to speak for their connection to the land, a theme that comes up repeatedly.

They write in Spanish to reach a wider audience, not just in the mainstream culture but also among other indigenous people who speak Spanish. Now the English translations may help them reach indigenous people in the U.S. and Canada.

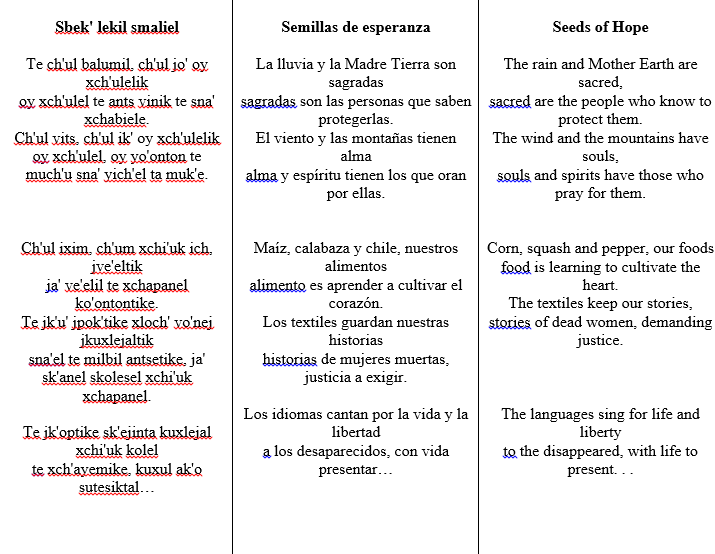

“Seeds of Hope,” by Xun Betan, in Tsotsil, Spanish, and English

W&W: How do you go about translating across texts that are typically bilingual? Can you think of instances where the Mayan language and Spanish language diverge, such that you will not, by definition, capture the full meaning of the two texts?

SS: As I mentioned, I’ve tried to learn Tsotsil, and made some progress, but would have a long way to go before I could work directly from that. Tseltal I haven’t studied specifically. The two are similar, somewhat like how Spanish and Portuguese are similar. They’re both in the Mayan language family which, according to indigenous Guatemalan scholar Victor Montejo, includes 31 languages.

So, I work from the Spanish, but I can make out some words or phrases from the indigenous versions. And sometimes they don’t seem to match that well. As can often be the case with translation, certain words or phrases in one language may not have a direct correspondent in another. For example, Adriana Lopez’s poem “Desolacion” opens with “Vino la malicia que levanta el ojo.” A direct translation would be something like “Came the malice that raises the eye.” I wondered whose eye she was talking about, why it was just “el ojo” and not both eyes, and why malice had this effect on it. Lopez explained to me that in her Tseltal version, which opens “Tal te bolil ya slik sitil,” the phrase “slik sitil” is a common expression among the original people, and it means that our eye jumps or twitches if another person is saying something bad about us. This calls to mind the English expression “ears burning,” though in that case the talk need not be bad. Lopez did not feel there was a comparable Spanish expression. Also, she felt this approaching malice threatens not just one person but the community in general, and thus she does not identify to whom this eye belongs. For English, I went with “Malice came, our eyes shuddered,” using “our” to indicate this as a feeling many people share, and “shuddered” to convey the sense of threat feeling. I hope that helps get across the mood of Lopez’s poem, even though it does not convey the direct meaning of “slik sitil.”

W&W: Can you tell us a little more about how you decide what words to keep in the original Indigenous language?

SS: Generally the authors have already decided. They kept certain words in Tsotsil or Tseltal for their Spanish versions, so I kept them in English too. In principle, the idea that certain words or phrases are untranslatable, as Barbara Cassin’s Dictionary of Untranslatables proffers, informs my choices. We have footnotes and a glossary to help English speakers, and perhaps Spanish speakers, understand, but we don’t want to suggest that the English explanations mean the same thing. Ch’ulel could translate as soul, kuxlejal as life, pukuj as demon, but these words have different dimensions or implications in the indigenous Chiapas cosmovision. By leaving them in their original forms, it helps give a greater glimpse into these other worlds.

W&W: You work with and know personally many of the authors you translate in Chiapas Maya Awakening. How do they view the translation of their work into English?

SS: They have been nothing but supportive! They seem delighted to know their works are reaching a broader audience, and happy to answer any questions I have. I was back in Chiapas last summer and able to meet with most of the writers so they could review the Spanish and Tsotsil or Tseltal versions of their works before they went to print. All of them are involved in promoting their culture one way or another, beyond their writing. Miguel Ruiz Gomez has published a short novel—I believe the first in the Tsotsil language—and I’ve translated that one too. He’s now working on another novel.

W&W: Does knowing the author more closely effect how you translate their work?

SS: When I can ask them about it, it definitely does. I didn’t know the authors when I started, so I would make a lot of guesses, and keep written or mental notes to revisit certain matters later. Now that I do know them, those become actual questions I can pose to actual writers, rather than things to possibly reconsider.

W&W: The use of indigenous languages in literature is an important aesthetic and political goal of many writers. What is the point of promoting these literatures in indigenous languages if they must frequently be translated anyway?

SS: To combat that sense of invisibility. A scholar named Vitelia Cisneros pointed out that the use of indigenous or pre-columbian languages implies by its mere presence the historical processes that have molded postcolonial reality. And I’ll add that it also implies an alternative view of that reality. If we value education, we must be aware that it flows both ways, that we have something to learn from anyone we might teach. It is an ongoing aspect of comparative literature that we want to expand our awareness of various cultures even though we know we cannot learn so many different languages and cannot fully appreciate their writings in translation.

W&W: You mentioned the challenge of learning the language and translating it in itself; what other challenges or obstacles do face working with the writers, their content, or even the publishing houses? Do politics, or the writers’ intent behind the work have an effect on your translation?

SS: Political concerns are in the back of my mind, and when translating I try to keep them back there. I hope the works can speak for themselves. So, the best answer might be that I don’t know how much politics affects the process, and I’d like to keep on not knowing. A challenge is that since so little work has been done on translating Tsotsil and Tseltal to English, I don’t have much history to draw from. But that’s also part of what makes it exciting! Not that I’m the first person to do this. Some who came before me include Robert Laughlin, Ambar Past and Gary Gossen. I encountered their work during my master’s program at San Diego State, and it informs my choices.

W&W: How long have been people been writing in Mayan languages using Latin script?

SS: Since the sixteenth century, but not continuously. Spanish priests set about learning indigenous languages shortly after the Conquest, so they could instruct the natives in the Catholic faith. Thus the alphabets have been there for centuries, but not many people were using them. As far as modern Mayas writing in indigenous languages, in Chiapas at least, that probably dates back to the 1960s, as scholars were taking new interest in indigenous languages and cultures, and priests following liberation theology started seeing indigenous culture not as something that had to be destroyed to save people’s souls, but something valuable for its own sake, to be saved along with the souls. More indigenous people wanted to learn to read and write in their own languages. I’ve mentioned the collections of folk stories. I think this is something you might see anytime literacy starts to spread in a culture: the first impulse is to commit the oral tradition to paper as a way of preserving it. Then sometime later people start feeling their creative impulses and wanting to write new, original stories.

In Chiapas, the Zapatistas helped inspire indigenous people to see themselves as capable of many accomplishments. If Indians could outmaneuver and stand up to the national military, what else might they be able to do? The Zapatistas have made education one of their most serious aims, so even people not formally associated with them—and as far as I know, none of these writers have any such association—might find motivation through the Zapatistas’s ideas and accomplishments.

W&W: What’s next for Sean Sell?

SS: My next class, in a few hours! In the midst of a PhD program, it can be hard to look beyond the next few days. But, I do have other pieces I’ve translated, so I’m looking to get more of them published. And for my dissertation, still of course in the formative stage, I’ll examine works from Chiapas in the context of decolonial Latin American literature, details much to be determined. But whatever I do, I’ll keep following the progress of the writers who are hoping to wake up the rest of the world.

Kelsey Woodburn is an Editor-at-Large for Mexico at Asymptote and an incoming MA student at Western Carolina University studying English with a concentration in Professional Writing.

Paul Worley is Asymptote‘s Editor-at-Large for Mexico and a professor of English at Western Carolina University.

*****

Read More from the Blog Archives: