The first time I heard Abnousse Shalmani speak was her TEDxParis talk, which opened with: Oh, putain de bordel de merde [oh, motherfucking shit]. The auditorium echoed with scattered titters of discomfort and appreciation. “It’s ugly, all these curse words in a woman’s mouth, at least that is what parents tell their daughters,” Shalmani continued, “but I think the opposite: that all these swear words—words of the mouths of men—in the mouths of women, are indispensable.” In the remainder of the talk Shalmani exhibited through personal anecdotes and precise historical and literary analysis how sexism and misogyny, through the constraints on women’s bodies, permeate the Republic celebrated for equality and liberty.

To Shalmani, freedom begins with the liberation of the body and the assurance of one’s ability to fulfill corporal desire without limits or restriction. In her first book, Khomeini, Sade, et Moi [Khomeini, Sade, and Me, tr. Charlotte Coombe, World Editions]—which toes the line between memoir, manifesto, and novel—Shalmani expands and elaborates upon these foundations. In September 2016, I had the opportunity to interview the author about her book, feminism, and the conundrums facing contemporary France

Nina Sparling (NS): In Khomeini, Sade and Me, you make the case for a renewed humanist project, a way past all forms of extremist thought. But you get there via an unusual intellectual trajectory: through the libertine literature of authors like the Marquis de Sade or Pierre de Louÿs, both of whom are often associated with the search for extreme—even cruel—sensations and thoughts. Is it possible to reconcile humanism and libertine literature?

Abnousse Shalmani (AS): Above all, I plead for the liberation of the female body. And that liberation is impossible without the erasure of prejudice. The intellectual paths I’ve taken might seem unusual, but under closer scrutiny, their trajectory fits perfectly within the tradition of Enlightenment thought.

I first ‘encountered’ Pierre Louÿs, the prolific erotic writer. What struck me most about this lover of Beauty (“Beauty is made from Greek perfection crowned with Oriental grace,” he wrote) in his erotic poems and pornographic novels was his playful vision of flesh, of sex. Born in Teheran under the Islamic Revolution, all I knew of the body was the drama it provoked, the gravity with which my world covered up the female body, the danger it represented. To read a poet—at fourteen—who laughed about the body, about sex, who took pleasure in both, this took the drama out of the body. I began to see my body as something besides a forbidden place. It began as a literary step; the politics followed.

Later on, my family had moved near the Bastille in Paris. Amidst feelings of displacement in a new country, I discovered the history of France, most of all its great revolution: the French Revolution. I already loved erotic literature thanks to Louÿs, which brought be to the libertine literature of the Enlightenment through that. Here I must specify the difference between libertine literature and the Marquis de Sade. Libertine literature is playful, political, and freeing. It often presents the conflict between women from disadvantaged backgrounds and the prejudices of the ancien régime. Following a death, an accident, a new job, the heroine must confront a world heavy with prejudice and prohibitions. But she also meets people and reads books—which allow her to discover her natural rights and self-liberate. Libertine literature deals a heavy blow to the rigidity of the ancien régime. As a political weapon, it destabilizes the church, monarchy, and royalty with exceptional levity. Libertine literature questions the position of women, the Third Estate (the common people), and birthright. The literature liberates and allows for the birth of the autonomous citizen. And to accomplish this, libertine literature considers that the liberation of women and men occurs in spirit but also in body—one cannot happen without the other. Sex is the proof in action of freedom from the prejudices that hinder Reason. In a time when the Church condemned sex without procreation, libertine literature restores desire. It is pure humanism.

The Marquis de Sade is not a libertine author. He stood alone in the eighteenth century and stands alone today. He is unsurpassable. I discovered Sade following my assiduous reading of libertine literature and I was obsessed…Where libertine literature is best read lying in a hammock, a glass of wine nearby, Sade is best read seated at a desk, pen in hand, gravely. Sade is literature plain and simple. The Marquis—imprisoned for twenty-seven consecutive years by successive regimes—placed human desire above any moral scheme. He refused any prohibitions. He believed woman equal to man, the poor equal to the rich, the aristocrat equal to the peasant. He drew the line between those with temperament and those without—the victims are those without personality, incapable of using Reason. [In his work], executioners look beyond prejudices, take responsibility for differences, and lead the world as they wish.

Reading Sade is violent. But his work allows us to reassemble. I often return to Sade, likening him to a vacuum cleaner for prejudices.

We rise from the ashes with Sade; we learn to exist at the heights of the marvelous gift that is free will.

NS: Does the liberation of the female body depend upon libertine thought? The polemic around wearing burkinis in France reminds us that a woman’s liberty to inhabit her body as she chooses continues to solicit strong emotions, which come out in debates around identity politics that often appear (especially to an American observer) confused if not contradictory. What do you think?

AS: The liberation of a woman’s body happens precisely through its de-sexualization. Men have two bodies: a public body and a private body. Women are systematically reduced to their private bodies, their sexualized bodies. Libertinism in its contemporary sense doesn’t free women. Libertinism in its original sense—that of the eighteenth century—liberates women from the fetters of the Church by proposing free sexuality and access to knowledge, and therefore to freedom.

Since the Iranian Islamic Revolution we have been—in the West—confronted by political Islam. Islamism is built on prejudices that restrain women’s bodies. To cover the female body with a veil, a burqa, a hijab, a burkini, is to accept that said body is a site of desire and only that. To imagine that an ankle can provoke concupiscence in men is to accept the idea that women’s bodies are dangerous for men and thus cannot move freely through public space uncovered. When you talk to women wearing burkinis, they all respond that it is a question of decency, of modesty. And so what? The woman in a bikini isn’t decent? By unveiling her body, she provokes concupiscence? It’s repulsive. In the West, women and men both fought to liberate women from the corset, from the prohibitions tied to her gender. But for the past fifteen years now we’ve been supporting a regression: separatism of the sexes, new restrictions on the female body in public space. We fought hard to win our place in public.

A veiled woman is not a free woman. She is a woman who considers her body a taboo. A woman’s body is not taboo; it is equal to that of a man. It should possess the same rights and exercise the same duties. To cover women is to separate the sexes. It is to return to the time of the ancien régime. All religions restrain the female body.

That being said, I’m against the creation of a law that would prohibit the burkini or forbid the veil in public. It is up to us—the progressives and the feminists—to prove the regression that veiling women represents. It is up to us to sway retrograde political Islam with our ideas grounded in the Enlightenment. It won’t happen overnight, but we will win.

NS: In the book you talk about your university education and your thesis, where you proposed to study women, love, and sex in postwar France and Italy. Your female professors (theoretically leftists) were shocked by your choice of subject. The scene is a brilliant dark comedy. Does French feminism have a particular rigidity? Do you find that its feminist discourse has changed much in the past few years?

AS: I had a lot of fun writing my thesis! What shocked my professors the most was the title: How do women make love? This was the heart of my questioning: how was the female body envisaged sexually and amorously after the World War II? How do men dread this body in France and in Italy? How is the postwar woman born, after the head-shavings, after the rapes? How does a woman liberate herself from the traditionalist straightjacket?

There is rigidity in all –isms; ideology is rigid by definition. I am a universalist-feminist for this reason. I make constant reference to the Enlightenment because it isn’t a matter of ideology, but of tools. Enlightenment thinkers bestow us with tools (free will, the separation of powers, the autonomy of the individual in the community, Reason as a compass in place of the superstitions of the Church, and so on). It is up to the citizen to liberate himself. French universalist-feminists are not rigid. All others are. To be a universalist-feminist is to wholly commit to the idea that a woman, no matter where she is, where she lives, merits the same rights as men. It reminds us that no tradition, no custom, no religion holds up before the law. And the law is equality between men and women in all respects.

These new essentialist-feminists who speak about cultural belonging muddle the discourse through fantasizing a world where equality is possible when women must cover themselves but not men. This is not possible. Equality plays out at the level of the body and engages the visibility of this body. That a man can walk about with his legs in the open air, bare-chested, without being provocative, but that a woman must cover herself from head to toe as not to provoke desire is an equation that all feminists must refuse.

NS: In 2010, the American historian and researcher Joan Wallach Scott published The Politics of the Veil, a controversial book that sought to complicate the debates around the veil in France. Wallach focuses on certain oversimplified oppositions (tradition v. modernity; public v. private; individual v. universal; identity v. equality), most notably the universal ideal (so closely tied to laïcité) at the heart of the French nation. Major debates about the position of the ‘other’ in French identity and multiculturalism, especially concerning Muslim culture(s), seem more challenging than ever. Do you think your book can shatter some of the assumptions about French culture in this regard? Is there a way out of the social and intellectual gridlock in France?

AS: For me the problem at stake is simple, precisely because I came up in two cultures: Give me a single country in the world where the veil is imposed or has became the norm under the pressure of political Islam (as in Egypt or Tunisia where thirty years ago there wasn’t a veil in sight) and where women and men are equal. In all Arabic-Muslim countries, women are politically, legally, culturally, sexually, and socially rendered inferior. Despite the fact that in Iran, Tunisia, and Morocco, more students are women than men, in the working world, women hold only 17 percent of salaried jobs. While Tunisia may represent incredible hope for all Arabic-Muslim women, they still remain unequal inheritors. In Iran, the testimony of a woman in court is worth half that of a man. In Saudi Arabia, a woman is considered a minor her whole life and can do nothing without the approval of her guardian. Go out of your way, reference Islamic feminists who swear hand over heart that the veil liberates, that religion allows autonomy—it is stupid and it is a lie. A woman is not accessory to a man; she is his equal. And all religions fight this idea. There cannot be freedom beneath the veil. There cannot be individual freedom under a religious regime.

Political Islam is a strong ideology, present all over the world. Since the birth of the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928, it has never stopped growing. The everyday problem we live in France is not religious but political. The ferocious will of political Islam to reduce the identity of anyone with a Muslim background to Islamism and nothing more, creates the nauseating atmosphere where the female body is the most visible stake. I believe in the laws that guarantee my equality. Political Islam believes in birthright. The relativist discourses in France abandon immigrant citizens to the Islamists, and this worries me. It is more and more difficult to call oneself Atheist-Muslim or, in certain neighborhoods, to refuse external signifiers of faith. The pressure to belong is too strong.

France in particular is built upon cosmopolitanism, never multiculturalism. The difference is that a cosmopolitan society sees a citizen before her origin, while a multicultural society never gets past the origin. Difference is beautiful, and what I prefer. But this is not what political Islam is after; it seeks to separate citizens by creating a specific Muslim community. That I refuse.

Finally, I find it unjust and ethnocentric on the part of Western feminists, liberated from the yoke of the Church, who have battled against retrograde conceptions of the female body, site only of desire and motherhood, who kicked clerics in the ass, to refuse Muslim women their autonomy. To consider that because they had the chance (and the misfortune) to be born Muslim, they will not have access to the same freedom. That is complacent and indulgent.

Joan Wallach Scott benefitted from the sexual revolution. She benefitted from the upending of mentalities that saw women in the West enter the public sphere, go to college, climb the ladder in the workplace, direct their own lives. I find it criminal to refuse the same revolution for Muslim women, to consider that it is their culture and so they must remain prisoners without hope of one day being equals.

NS: The English-language edition of your book is categorized both as a “fictionalized memoir” and as “part novel, part manifesto.” Is the eighteenth century literary tradition of the philosophical novel, found, for example, in the works of the Marquis de Sade, an important influence for you? Not only for its critical spirit, but also on a stylistic level?

AS: I have always liked blurry lines, ambiguities, in-between-ness. I wrote Khomeini, Sade and Me as part-story, part-pamphlet. It is my first book and it is a long cry punctuated with bursts of laughter.

I’m a big reader, and if I’m influenced by libertine literature that knows no bounds, I am just as much nourished by the magical realism found in the likes of Gabriel García Márquez or Salman Rushdie. The mixture of genres allows a break from ever-stifling reality. For me, literature is the place of absolute freedom. And this is also why, in literature, I can gather all my contradictions, my two cultures, the Orient and the Occident; they marry, they overlap. Literature allows me the coherence that all exiles search for.

NS: Any manifesto looks necessarily looks towards the future, towards hope. What potential do you see for a Feminist Spring in the Middle East? What would that look like?

AS: The Feminist Spring will be the sexual revolution. The day women re-appropriate their bodies and master their sexuality, the day when they unveil themselves in considering that a woman’s body is neither taboo nor dirty will be the day when they will be politically autonomous. There is no other possible way.

This interview was conducted over email, and has been translated from the French by Nina Sparling.

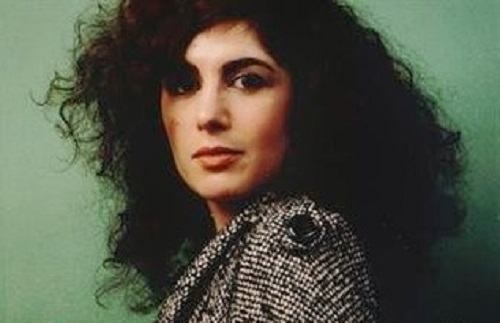

Abnousse Shalmani was born in Tehran in 1977. In 1985, her family went into exile in Paris where she studied history and became a journalist and short-film maker.

Nina Sparling writes, translates, and works at the Bedford Cheese Shop.

*****

Read More Interviews: