In early November, the picturesque, if rather overcast hills and vineyards along the Danube in Spitz, Austria provided a luscious backdrop to literary discussions ranging from Haiti to Hungary, Brazil to Burkina Faso, Slovenia to South Africa and Brazil to Zimbabwe. Headlined “The Colonists”, the European Literature Days 2016 brought together writers, translators and literary critics to debate cultural appropriation and colonialism in literature in both the literal and metaphorical senses, with literary readings and wine tastings to boot.

© Julia Sherwood

“Every country in the world is a hostage of its history from which there is no escape,” German reportage writer Hans Christoph Buch declared in his keynote speech (reproduced in full in the daily Die Presse). Since first visiting Haiti—the country of his father’s birth—in 1968, Buch has traversed the world, concluding that, although he might have written about the Caribbean and Africa, experience is not transferable across continents. But isn’t a white author writing about Haiti stealing the country’s stories? Do writers have the right to write about countries that are not their own or does it turn them into colonists? Media and cultural scholar Karin Harrasser posed these questions to Zimbabwean lawyer and novelist Petina Gappah and Cuban author and cultural journalist Yania Suárez.

Hans Cristoph Buch © Sascha Osaka

They certainly do, according to Gappah. But with the privilege to tell stories, especially those that are not yours, comes responsibility to tell the truth, she added. She deemed Hans Christoph Buch to have passed this test with flying colours. She stressed the value of the external gaze but warned about striving for authenticity, which is the death of fiction: “If you go down the rabbit hole of authenticity you end up with memoirs.” Suárez agreed that people have the right to write about other countries but only if they’ve spent enough time there to get to know their surroundings properly. Those who haven’t immersed themselves in the culture often misrepresent and fetishize Cuba, for example, creating fantasy narratives and appropriating its recent history to support their own romantic ideas (ideas echoed only a few weeks later by the accolades heaped upon the late Fidel Castro).

Petina Gappah © Sascha Osaka

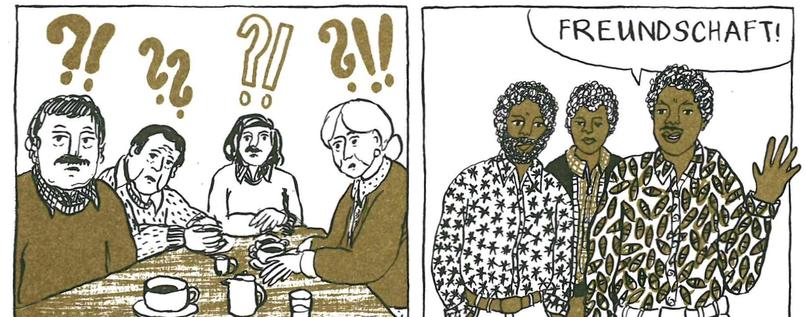

On a panel chaired by Christoph Gasser, German comic writer Birgit Weyhe and South African artist Anton Kannemeyer offered a different take on colonisation and authenticity. Birgit Weyhe felt that ‘settler’ would have been a more fitting label for her hippy mother who raised her in Kenya and Uganda. Comfortable as Weyhe is reflecting her own experience in her work, she hesitated before embarking on a book that deals with a little-known chapter in the history of colonialism in two countries she was less familiar with. Fortunately, she has overcome her doubts and the result is her graphic novel Madgermanes (a pun on ‘Made in Germany’ and ‘Mad Germans’) that tells the story of workers from Mozambique, lured to East Berlin for cheap labour between 1979 and 1991.

From Madgermanes by Birgit Weyhe

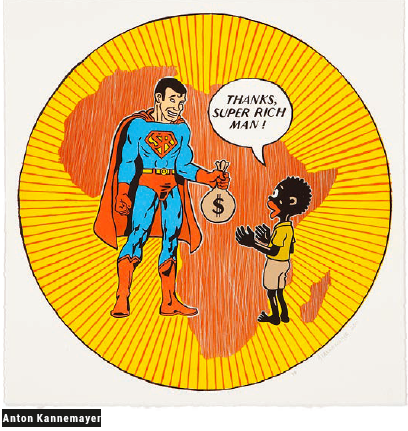

And what about white South Africans—do they have the right to criticize present-day South Africa? Some who take offence at Anton Kannemeyer’s politically incorrect comics and drawings, such as Papa in Afrika, a parodic take on Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo, seem to think so. Yet Joe Dog, as Kannemeyer is known, is adamant that although he is white, as a South African citizen, he is entitled to criticize the current authorities in his country.

Two British writers based abroad—Priyah Basil, who relocated to Berlin a few years ago, and novelist Tim Parks, who has lived in Italy since 1981—continued the heated debate about authenticity. “Your origins are never a question of geography, in fact they overflow all geographies,” argued Parks. He wondered aloud if reality can ever be depicted without creating something new, as a depiction will always leave something out and select other things as focal points.

Basil drew a distinction between writing fiction, in which writers can use their imagination—she called it“a dance where no move is wrong”—and political essays, which she says must stick to the facts of one’s experience—more “like marching and having to keep up”. Vienna-based Swedish journalist Carl Henrik Fredriksson raised another aspect of colonialism, pointing out that English has become a dominant language that offers its users a wider reach and privilege, spawning ‘international literature’ written in English. “We grew up thinking that great literature meant modernists such as James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence, because they changed language,” said Parks. “This kind of writing resists translation, but if we start writing texts that that travel well, linguistic innovation will be lost.”

One of the conference’s highlights was a presentation by Austrian Rüdiger Wischenbart, with Yana Genova (Bulgaria), Miha Kovač (Slovenia), and Gábor Csordás (Hungary), of their 2016 Diversity Report. It offers fascinating insight into the ways literature travels across borders. Their study has assembled data from translations of some 250 contemporary authors of diverse backgrounds in over 10 languages. Numerous case studies highlight key developments in the past five years, such as patterns of success among recent blockbuster authors, the impact of major awards on sales of translations, the role of national and European translation grants, and the recent emergence of new digital platforms and models of publication, promotion and collaboration.

Some examples of these new digital models were introduced in another session: Anja Kovač presented Versopolis, a Slovenia-based online platform promoting young European poets with events around the world (a kind of European cousin of Asymptote with a mobility scheme attached) and British writer Lucy Popescu illustrated how crowdfunding can work in the world of publishing. She brought up the publication of A Country of Refuge, a collection of essays and stories funded by online donations via Unbound, as an example.

Returning to colonialism, Priyah Basil noted with surprise that the term “third world” was still in use and that anyone could still entertain the notions of ‘good colonialism’ and ‘benevolent empire’. In her view, the UK is in denial about its empire, and this lack of engagement with the country’s past generates delusions of grandeur—which helped bring about Brexit. A different kind of denial occurs in Brazil, as novelist Rafael Cardoso pointed out in a panel focusing on Latin America. Brazil is guilty of a kind of internal colonization, perpetuating a myth of cultural and linguistic unity and suppressing the heterogeneous character of a country that, in addition to its vast number of indigenous languages, was home to the second biggest German-language press outside Germany until World War II.

Cardoso explores his own German connections in his most recent documentary novel, Das Vermächtnis der Seidenraupen: Geschichte einer Familie, 2016 [The Legacy of Silkworms: A family history]. He reconstructs the life of his great-grandfather, a German Jew who counted Rosa Luxemburg and Albert Einstein among his acquaintances before emigrating to São Paolo. Hungarian writer (and past Asymptote contributor) Zsófia Bán, who was born in Rio de Janeiro, mentioned that in Hungary, Brazil is mostly seen as an idealized, imaginary place. That her stories, such as Venom, from which she read in Spitz, are set far from her homeland is still unusual in Hungarian literature, where women writers have only recently started to make their mark.

Rasha Khayat © Sascha Osaka

Gender disparity has also marked the German book market, and the gap, as translator Katy Derbyshire pointed out in an article on LitHub, is even more pronounced in translation: “Only a tiny fraction of fiction published in English is translated, and only about a quarter of that translated fiction was originally written by women”. On the last evening in Spitz, Rasha Khayat—one of the female authors Derbyshire regrets has not yet been translated from German to English—read from her debut Weil wir längst woanders sind [Because We’re Elsewhere Now]. A representative of a new generation dubbed “Migrutanten”, a cohort of debuting authors with a migration background, Khayat is a translator-turned-novelist who draws on her experience of growing up between Saudi Arabia and Germany on her blog, West-östliche Diva [A German Window on Arabistan].

Literary critic Gerwig Epkes introduced Khayat and—in an increasingly spirited way, as the wine tasting proceeded—four more young writers: Petina Gappah offered a sample from The Book of Memory, Estonian author Peeter Helme read from his novel Am Ende der gestohlenen Zeit [At the End of Stolen Time], Slovenian novelist Gabriela Babnik shared a piece of her EU Prize for Literature-winning novel Dry Season (Istros Books, 2015, tr. Rawley Grau) and Munich-based Swiss writer Jonas Lüscher presented a highly entertaining teaser from his novel, Frühling der Barbaren [Barbarian Spring].

Over the three exhilarating European Days of Literature this year, the most memorable moment for me was when two writers and a publisher from three different places around the world shared the same story: each, at age sixteen, felt their life was changed forever by a chance encounter with poetry in translation. In a small bookshop in Basra, Iraqi, writer Najem Wali came across a volume by Rilke; in the French provincial town of Niort, novelist Mathias Énard discovered the poetry of Badr Shakir al-Sayyab from Basra: and in Pécs, publisher Gábor Csordás chanced upon the work of Vasko Popa, a Serbian poet with Romanian roots, in a Hungarian translation. What more proof do we need of the usefulness of translated literature and the power of poetry to transport, rather than colonize, young minds?

Photo credits, Osaka.

Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, which was then part of Czechoslovakia. After working for Amnesty International for over 20 years, she became a freelance translator in 2008. Based in London, she is editor-at-large with Asymptote, the international journal of translation. Jointly with Peter Sherwood, she has translated into English books by Daniela Kapitáňová, Jana Juráňová, Peter Krištúfek and, most recently, Uršuľa Kovalyk’s The Equestrienne from the Slovak; and a novel by Petra Procházková from the Czech and Lullaby for a Hanged Man, a novella by Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki from the Polish. She has also translated the latter into Slovak, as well as Tony Judt’s The Memory Chalet.

*****

Read more dispatches from around the world: