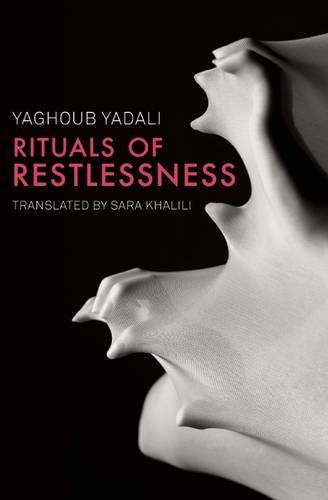

Navid Hamzavi and Asymptote’s long-standing Contributing Editor Aamer Hussein review Yaghoub Yadali’s Rituals of Restlessness, translated from the Persian by Sara Khalili (Phoneme Media, 2016).

Nihilism in the Nietzschean sense is “one of the greatest crises, a moment of the deepest self-reflection of humanity. Whether man recovers from it, whether he becomes master of this crisis, is a question of his strength!”

Rituals of Restlessness by Yaghoub Yadali seems to have a nihilistic outlook on life. Kamran Khosravi, the protagonist, wants to get rid of his real life in a fake accident in order to construct a new life in unknown territory. He chooses an Afghan migrant to replace him in a car crash down in the canyon. Spiking his tea, he makes his victim unconscious, puts his own clothes on him, sets his car on fire and pushes it down the canyon to make others believe that Kamran Khosravi is dead. We never know whether he is just imagining doing all this or, as the narrative suggests, actually goes through with it and later regrets it; whether he makes an unsuccessful suicide attempt, or whether he’s just on his way back to his wife who has left him. Much of the book is taken up with these three lines of interwoven plot, without shaping either a solid character, or identifying a cultural or philosophical issue.

Whether Rituals of Restlessness even comes close to addressing that crisis in Nietzsche’s quote, whether it recovers from its dull narrative to explore this question in greater depth, whether it comes anywhere near reflecting on philosophical or ontological aspects of life is open to debate. The shallow characters, the superficial reading of folk culture in contrast to urban culture, and the lack of depth of social understanding, render the novel tedious and shut down a critical approach to it. The novel even fails to portray the roots of that restlessness so as to convey a better understanding of the antagonist’s logic for his (attempted) suicide, which in itself could have opened it up for broader interpretation.

“Simple. Engineer Kamran Khosravi would die in a car accident. Easy, done. He finished smoking his cigarette with chilling calm, so that for the first time in all the years he had smoked, he could enjoy lighting one cigarette with another and, without wetting his palate, not taste the foul tang in his mouth.”

Sara Khalili’s translation of this opening paragraph of Rituals of Restlessness is efficient, accurate and highly competent; what is lost in translation is, in the case, a result of the novel’s own narrative lacunae. It should be noted, however, that the Luri language which is generally spoken by Lurs (Iranian people living mainly in western and south-west Iran) and the sweet accent that Afghan people have while speaking Persian, which are a feature of the original text, are both almost impossible to convey in English, and so sadly did not make their way into this version. As a result, those who speak Luri and those who speak Afghan Persian (Dari) are all similarly rendered in the target language.

Much of the novel focuses on the protagonist’s sexual encounters, often with strangers. “He kissed her lips to stop her from talking. Then he moved from her lips down to her chin and neck. He paused on the hollow of her neck and slowly inched farther down to where the necklace would not sit still.” But contrary to some reviews claiming Yaghoub Yadali was sentenced to one year in prison for having depicted an adulterous affair which is central to the first section of the novel, the court’s decree actually rested on a race-based accusation, of which he was later fully exonerated. At first he was accused of being racist towards Lurs; many writers and intellectuals were opposed to this accusation, as the novel is by no means racist: rather, the author is trying to embrace the colourful cosmopolitan culture of Iran. Yadali was then cleared of all charges, as was expected. Though, needless to say, many Iranian writers have their fingers burnt in various ways in the censorial banality of the ruling regime.

More controversial for the foreign reader is the author’s treatment of his female characters. Though they outnumber the men, the women in the novel are sexual objects or predators, or merely cold and unfeeling. Whether this is meant to indicate the male protagonist’s misogyny or the dominant society’s prevalent attitudes is never quite evident.

The results of various literary prizes in Iran (Ritual of Restlessness is winner of the 2004 Golshiri Foundation Award) as in any other country, have been always controversial; however, the translation of Yaghoub Yadali’s book will hopefully pave the way for rendering other contemporary Iranian writers, whose insights and approaches are rather more innovative, into English.

Navid Hamzavi is an award-wining Iranian writer. He is currently doing his MA on Cultural and Critical Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. His works of fictions include the collections Rag-and- Bone Man, published in 2010, and London, City of Red, published in 2016 in Iran. His stories have also appeared in British publications such as Ambit and Stand.

Aamer Hussein is a contributing editor at Asymptote. He was born in Karachi in 1955 and has lived in London since the 1970s. A graduate of SOAS, he has been publishing fiction and criticism since the mid-1980s. His several works of fiction include the collections This Other Salt (1999), Insomnia (2007), and two novels, Another Gulmohar Tree (2009) and The Cloud Messenger (2011). He has edited an anthology of writing from Pakistan, called Kahani (2005). He also regularly publishes fiction and essays in Urdu, his mother tongue. His most recent book of stories, 37 Bridges, was published in India by HarperCollins earlier this year.

*****

Read More Asymptote Book Reviews: