Cabo de Gata, by Eugen Ruge, tr. Anthea Bell, Graywolf Press

Review: Sam Carter, Assistant Managing Editor, US

First published in German in 2013—when his In Times of Fading Light appeared in English—Eugen Ruge’s Cabo de Gata, out this month from Graywolf Press, might strike a familiar note for readers who have witnessed a surge in autobiographically-inflected works that frequently take the production of fiction as a subject worthy of novelistic exploration. Hailing from both the Anglophone world and beyond, such novels record the process of their creation or the struggles to even begin them, and Ruge quickly aligns himself with this approach in his tale of a writer’s attempt to get away from it all in the hope of figuring something out. “I made up this story so that I could tell it the way it was,” declares the dedication to this slender volume, and a more precise formulation arrives soon after as the narrator recalls a period in which “I was testing everything that I did or that happened to me at the same moment, or the next moment, or the moment after that, for its suitability as a subject … as I was living my life, I was beginning to describe it for the sake of experiment.”

While in Cabo de Gata, a small town on the Andalusian coast, the narrator quickly settles into routines designed to simultaneously distract him from blank pages and provide him with some inspiration to fill them. The local fishermen, whom the narrator visits on his daily stroll, can empathize with such difficulties: ¡Mucho trabajo, poco pescado! A lot of work for only a little fish—it’s a piscatory philosophy that applies just as well to the writing life. Ruge, however, proves to be an exceptionally gifted angler as he reels in catch after catch in what would seem to be difficult waters, namely a single man’s short trip to this seaside village.

Serving as a metronome marking out the rhythm of memories that constitute the novel, a refrain of “I remember” begins many of the paragraphs that have been expertly rendered by translator Anthea Bell. Far from repetitive or reductive, such a strategy instead seems somehow expansive, particularly when we are reminded that, “fundamentally memory reinvents all memories.” Both the vagaries and the vagueness of memories—“I remember all that only vaguely, however, like a film without a soundtrack,” remarks the narrator in a line that will be hard to forget—serve as the subjects of reflection that find their counterpart in the rhythms of the sea and the surrounding Spanish countryside.

“On the surface, it’s a sort of road-movie book,” Ruge said in an interview. “It describes a journey, but more and more this journey turns into an inner journey. On the surface, not very much happens, and maybe this is the theme, this what the book is about: the question of living intensely.” Stocked with felicitous phrases that construct an elegantly composed series of “those oscillations of the mind that we call memory” that ultimately provides readers with their own intense experience, Cabo de Gata closes with an episode regarding the appearance of a mysterious feline, which prompts the narrator to pose a series of questions a reader might ask of the novel itself: what is it trying to say? why has it come into my life now? But what we know to be true of cats holds true for Ruge’s work as well: it’s futile to impose too many of your own demands since it’s far more rewarding to sit back and take what comes.

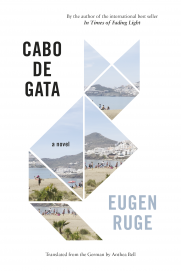

Monsieur de Bougrelon, by Jean Lorrain, tr. Eva Richter, Spurl Editions

Review: Nina Sparling, Blog Editor, US

It must have been something, an Amsterdam winter in the mid-nineteenth century; the northern gloom hanging heavy over brackish canals reflecting soot-stained gingerbread houses, giving woolen overcoats a permanent odor of must and mildew. In Monsieur de Bougrelon by Jean Lorrain, from the young independent press Spurl Editions, two Parisians travel to the damp city in the winter months seeking escape. In the grim and frigid climate of the northern port city where the travelers expect to find charming canals and high art, they instead encounter madness.

Soon after their arrival, warming themselves with liquor and the prospect of the company of girls “red as roast beef and as curly-haired as a sheep” in a red-light district brothel, they chance upon this obscure, quirky book’s narrator—Monsieur de Bougrelon. He struts into the brothel as if marching on stage: “Swaggering, with his waist cinched in a big piped redingote, his shoulders broad and his chest thin, and an enormous top hat tilted to one side…He had the demeanor of a prison guard, of an old leading man.” Monsieur de Bougrelon begins to speak at once and continues nearly without pause for the length of the novella.

The nameless travelers (one of whom takes over the novel’s narration in the rare moments between Monsieur de Bougrelon’s extended tangents) are at once alarmed by and addicted to his eccentricities. Monsieur de Bougrelon is a French expatriate himself and natural guide for the young men on their tour of the unfamiliar city. Their accidental guide of inexhaustible breath tells tales of his mysterious former companion Monsieur de Mortimer (who may also have been a lover) alongside declarations about the tackiness of Dutch fine art (“The Flemish School is a fishmonger’s stall…talk to me of Velázquez, rather!”) and his taste for well-aged liquor. He sports a well-greased mustache and wears heavy, caked makeup on their trips to museums, costume galleries, and brothels.

His ornamented tales account for the vast majority of the short book. He expresses tragicomic nostalgia for days gone by in rambling paragraphs that mimic the texture of rococo furniture: embellished to the point of excess. The visiting Frenchmen all but disappear beneath his words—a reluctant and curious audience for Monsieur de Bougrelon.

Much of this may be intentional—Jean Lorrain was known for his willingness to provoke and shock. One of the few openly gay writers of his time, he was a fierce social and political critic who celebrated his bourgeois queerness while remaining an anti-Semitic misogynist and advocate of France’s colonial pursuits. His interest may have been rather less in literature than in perverse writing that challenged the conventions (in form and in content) of his time. The result is by turns amusing and awkward.

In its celebration of all things odd and irregular, Monsieur de Bougrelon embraces the peculiar and dark social periphery. The characters show no restraint and demonstrate no fear of insult. Monsieur de Bougrelon has little regard for the normative—should and ought are absent from his robust vocabulary.

Nevertheless, the novel never quite delves below its decorated surface. An authorial self-awareness permeates the text. The novel never gathers the momentum—whether through plot or character development—to stand on its own. Once the reader adjusts to the oddities of the personality and language, the characters tend towards caricature, which grows tedious as the novella progresses.

Translated by Eva Richter, the English text demonstrates an exceptional sensitivity to historical French and literary references. The footnotes throughout the work enrich and provide essential context for this obscure 19th-century work. She produces an English-language text that is by turns mocking, provocative, and tragic. The texture of the language is rich and luxurious, and its black comedy obvious and catchy in English.

The Gravity of Love, by Sara Stridsberg, tr. Deborah Bragan-Turner, MacLehose Press

Review: Hanna Heiskanen, Blog Editor, Finland

Though the rhetoric of some modern politicians might suggest otherwise, there’s no denying that many of the topics once taboo—race, sexuality, the subjugation of women—are now discussed openly, compassionately, and rationally in the public sphere. Mental illness, however, remains of the last frontiers still largely unexplored; a topic that makes you recoil and turn a blind eye, perhaps precisely because it is so human. It’s an awareness that you, too, might one day go to bed of sound mind, and wake up the next to a black dog you are unable to shake off. Writing intelligent fiction about mental illness that doesn’t succumb to looking down on its protagonists is a great feat.

The topic is in safe hands with the Swedish author and playwright Sara Stridsberg (b. 1972). With a background in law, Stridsberg has already collected a handsome list of accomplishments: since her debut, Happy Sally, in 2004, she has been nominated twice for Sweden’s most important literary award, the August Prize, and been given the Nordic Council’s Literature Prize in 2006 for her second novel Drömfakulteten [The Dream Faculty]. Since 2016 she has held one of the permanent chairs on the Swedish Academy, which decides on the laureate for the Nobel Prize in Literature in addition to having a regulatory role on the Swedish language.

Beckomberga: Ode till min familj [The Gravity of Love] is Stridsberg’s sixth novel and the first to be translated into English. Based on and named after the real-life psychiatric hospital operating in Stockholm between 1932 and 1995, it’s a story told principally from the point of view of Jackie, whose father Jim suffers from alcoholism and mental health issues, and whose mother Lone is either mentally or physically absent from her life. Comprised of short chapters occasionally less than a page long and with frequent flashbacks, the novel blends the factual history of Beckomberga with the fictional saga of Jackie’s family. But it could be anyone’s story, uncovering a chain, or a whole society, of broken people for whom unhappiness is nigh unavoidable; it’s everyone’s destiny, whether you are wearing a white coat or a straitjacket.

While still a young boy, Jim witnesses his mother take her own life. He grows up to be a man softened by substance abuse and separated from the world by a paper-thin shell.. He is a man with nothing to look forward to except death: “The instant before it all goes black there’s no fear, just a faint light at the edge of consciousness. If time no longer exists, then neither does suffering. If space has come to an end, there’s nothing to be afraid of. It’s a sort of paradise, Jackie. It’s a paradise that beckons.” And yet he isn’t utterly unhappy: he is admitted, rather than committed, into Beckomberga, which throughout the story grows into a symbol of the Nordic welfare state, and in which he can finally experience a degree of joy. The hospital seems to be in a constant state of flux, though the people within never change, and so Beckomberga’s residents and staff survive from decade to decade. Until the facility closes and the patients are left to fend for themselves.

Much of Jackie’s story is about trying to come to terms with parents who are kind, good people, but unable to love her, disappearing and reappearing in her life. She seeks solace in Paul, one of the hospital’s patients who is much older than her. She wraps herself in a secondhand fur coat that she refuses to let go of even in the unforgiving summer heatwave. When her son is born, it’s down to her to try to end the chain of unhappiness.

The Gravity of Love comments on the social democratic dream in which all members of society are justified to a good life, directly mentioning Olof Palme, the Prime Minister of Sweden from 1969–1976. Palme’s mother was treated at the hospital, and her murder deeply upsets one of the characters. The patients are occasionally taken to parties outside of the hospital by staff in an attempt to create an illusion of normalcy. Stridsberg’s narrative makes you question the definition of sanity: are the members of staff considered sane simply because of who they are? Perhaps everyone in this world is equally sane or insane.

All the events in The Gravity of Love are framed by Stridsberg’s vivid portrayal of Nordic nature and wildlife over the seasons, which almost become additional characters. Deborah Bragan-Turner’s wonderful translation loses nothing of the spell Stridsberg casts on the reader.

***

More Updates from the Asymptote team: