Penny Hueston, translator and editor at Text Publishing—a Melbourne-based independent publishing house—shared with me the process of translating the inimitable French author Marie Darrieussecq, how her editing and translation processes relate, and her next translations we have to look forward to.

Madeline Jones (MJ): How did you first begin translating?

Penny Hueston (PH): After spending about four years in Paris doing post-graduate studies, I returned to Melbourne and was asked to translate various articles—by the literary critic Gérard Genette, for example—for the French issue of a literary magazine, Scripsi. I also translated, with the poet John A. Scott, poems by Emmanuel Hocquard and by Claude Royet-Journoud. Poetry must be the hardest writing to translate.

MJ: Would you say translating followed naturally from your editing career, or how do the two processes relate to one another for you, if at all?

PH: I suppose you could say that translating is a form of editing. In a sense, both my fields of work are about being more or less invisible; at least that is how I conceive of my work as an editor. Julian Barnes seems to nail a similarity between the two processes: “Translation involves micro-pedantry as much as the full yet controlled use of the linguistic imagination. The plainest sentence is full of hazard; often the choices available seem to be between different percentages of loss.” Damon Searles’ take is that translators “gerrymander unscrupulously”, which could also apply to editors! Javier Marias could be talking about editors when he says of translators: “You have to choose every word. And like an actor, you have to renounce your own style.”

Both processes are about having an intense relationship with a text. Identifying particularities, getting inside the text, as well as having a vision about style and voice. Translating is an act of empathy, of finding something like the appropriate “melody”, but keeping what is idiosyncratic to the writer.

I continued to translate once I’d become an editor, because I enjoy translating and think it is an immensely important contribution to literature. At Text Publishing, the percentage of translated books on the list is about 20 percent, which is very healthy. I edit a lot of the translations and, of course, being a translator myself helps me to understand some of the decisions translators make in their work. When I can refer to the original, in the case of Italian (for the novels of Elena Ferrante, for example), or French (for books by Yannick Haenel, Elisabeth Badinter, Hélène Grémillon, Muriel Barbery, Raphaël Jerusalemy, Nancy Huston, among others), it helps, in discussions with translators and authors, to ensure that the idiosyncrasies of the source language are in some way retained in English. The priority in translation, in my opinion, is to render the English idiomatic and fluid, so that we don’t have that unsettling sensation of reading translatorese—some kind of hybrid English. And this is exactly what an editor does, too, identifying knots in the fabric of the prose.

There are instances in translation, at a syntactical level, for example, which are similar to editing: as English is not gendered, the qualifiers and modifiers have to be closer together, so sometimes longer French run-on sentences of nouns and agreeing adjectives need to be broken up—just as one might suggest to an author in editing a text in English.

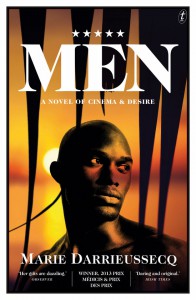

MJ: Your most recent translation, Men by Marie Darrieussecq, is about a French actress working in Los Angeles who falls for an actor-cum-director there. But though Solange is a recurring character in Darrieussecq’s books, Men is not a sequel to All the Way, for example, which you also translated. How did you approach translating a character and a voice that you’ve translated before, knowing that this book is a separate entity, and about a different Solange?

PH: Solange only appears in these two most recent novels by Darrieussecq. In All the Way she is a young adolescent stuck in a provincial Basque town. She is desperate to learn about sex, about relations between parents and children, between girls and boys, and between men and woman. In Men, Solange is in her thirties, she has had a child, whom she has more or less abandoned (he is living with her parents); she is doing bit parts in Hollywood as a mediocre actress when she falls for a charismatic black actor, Kouhouesso, who is intent on making a movie of Heart of Darkness in the Congo. Solange is desperate to play a role in his movie and in his life. The two books are completely self-contained and Men is not a sequel in any conventional sense.

But it is the same charming, self-obsessed Solange, eager to try new experiences, intelligent but naïve, obsessive and a bit ditzy. Just as it was not difficult to channel the voice of a confused, risk-taking teenager in All the Way, I found it equally enjoyable to give voice to a thirty-something woman still drifting, still looking for the perfect object of her affections. I always read my translations out loud as I go, especially when it is an interior voice like Solange’s. Darrieussecq cleverly narrates Solange in the third-person, but uses an interior point of view. So she has Solange narrating herself: “She, Solange, …” This technique allows for a fascinating double perspective on the character, a cinematic interior/exterior shot, a close-up from a distance, if you like, the ability to speak with all the intensity of subjective experience, but also to analyse the experience objectively. Until last year, Darrieussecq was a practising psychoanalyst and I wonder if the close-listening experience she brings to her novels is connected with that other part of her career.

I’m sure Darrieussecq had a lot of fun writing the character of Solange, through whose voice in Men she can play with all sorts of preconceptions about the French, about Africa, race, colonialism, bigotry, chauvinism, filmmaking, Hollywood hype, and of course, romantic love, sexism, and sex. Just as she did as a teenager, Solange fantasises about the man she thinks she loves and is forever imagining deluded scenarios and putting herself in extreme situations in order to somehow test his love for her—most of the time her illusions are shattered. But she is a survivor, and her ability to apprehend the bizarre side of things, especially the way her body connects with the physical world, suggested some of the tonal elements I tried to imbue her voice with in English—an openness to experience, coupled with a droll sense of her own shortcomings.

It was a joy to get back to Solange’s voice in Men. I feel as if I know Solange intimately; she has become a friend, like her author. Indeed, as Marie has said, Solange is her if she had not become a writer—all part of the “auto-fiction” element in Darrieussecq’s writing.

This is how, in an interview, Marie described the Solange of All the Way: “The contrast between what she thinks, what she says and what she actually lives was what interested me most, as a writer. I hope the book is both crude, cruel sometimes, and funny. And I like Solange because she’s a little philosopher who really likes to deal with the world. She’s also a ‘little soldier’, she’s valiant and so obstinate that she goes far beyond her own limits, sometimes without knowing it. She’s curious and she takes risks”.

MJ: Darrieussecq said in an interview in 2005, “When someone reads one of my books, I want them to feel as if they have looked through a new window it wouldn’t have occurred to them to open before, or even known was there. I don’t just want to show people a good time or make them laugh. To do this I need new sentences, as new as possible. I need to explode clichés, to see how they work from the inside.” You’ve certainly done justice to this goal of hers in the English version—the language is always fresh and stimulating. Was it challenging to work from French without expressions, idioms, or clichés, which have established meanings and oftentimes “easy” translations into other languages? How did you determine what would be analogously unfamiliar yet meaningful in English?

PH: It is true that reading Darrieussecq may sometimes not seem easy: she certainly does reveal “new” uses of language, “new” perspectives on common perceptions, surprising, shocking sometimes, both on the line, at a linguistic level, as well as at the level of ideas. That is precisely the mark of her genius: she shows us both the importance of clichés (as, literally, keys to our world), as well as their limitations, and tries to find other words and ways of exploring the ideas and feelings behind these clichés.

Right from the title and epigraph of this novel, Darrieussecq, who admires Duras’s own linguistic brilliance, is playing with language and notions of romantic love: the French title of Men plays on a quote by Marguerite Duras: Il faut beaucoup aimer les hommes. Beaucoup, beaucoup. Beaucoup les aimer pour les aimer. Sans cela, ce n’est pas possible, on ne peut pas les supporter. We have to love men a lot. A lot, a lot. Love them a lot in order to love them. Otherwise it’s impossible; we couldn’t bear them. Just as in so much of Darrieussecq’s writing, the word-play and irony is wonderfully implicit.

The language and the creation of the character are as one: inventive, poetic, and witty, every word counts. Darrieussecq is forever stripping back language to its essence, often minus syntactical elements, like subjects or verbs—just as Solange in Africa, a superficial French vedette who lands in this heart of darkness, is stripped back to almost nothing, once all her prejudices and the stereotypes she has lived by have been twisted, exposed and subverted. The visceral nature of her new world means that the characters and objects often fuse, subject and object become one, which is also part of the nature of Solange’s obsession with her man and with this strange place that is Africa.

At the same time, the sharpness of Darrieussecq’s imagery and language is precisely what reveals the superficiality of the film world she is depicting. Humour is also a great tool for this purpose. There is a brilliantly comic scene in which the egotistical French actor playing the steamboat driver in Heart of Darkness, and terrified of catching African diseases, insists that all the water for the rain machine used in filming the storm scene be bottled Évian water.

Solange is as if possessed, by the illness, the fever, of romantic obsession. Darrieussecq reveals what happens to a woman who is objectified by a man, or who allows herself to be reduced to a passive object: Solange feels as if she is disintegrating. One of the words Darrieussecq uses in many of her books is “atomize” or “pulverize”, for this state of disintegration into time and space. She often uses metaphors about outer space and the Earth and the Moon appear in capitals as if we are to see the characters and ourselves as particles operating in an immense void.

Darrieussecq is herself a translator, from Latin and from English (most recently James Joyce and Virginia Woolf), so I was fortunate to be able to ask her the occasional question. But in general, in translating tricky idioms or jokes, I try to stay as close to the original tone, imagery and meaning and, if possible, retain or find equivalent internal rhymes, alliterations, and rhythms.

In All the Way, Darrieussecq often uses words and expressions that connect with her Basque origins. Like Elena Ferrante in her Neapolitan novels, she uses dialect to express the obscene or the sexual layers of expression and is primarily concerned with the play of language(s) and their interpretation, how language shapes us. In All the Way the fault-lines between language and sex are a source of comic confusion for the adolescent Solange as she negotiates her sexual initiation. In the same way, the older Solange in Men is forever falling into the trap of making linguistic and cultural assumptions and misinterpreting so much. Translating Darrieussecq’s double-entendres and jokes, or finding equivalent nursery rhymes or teenage slang is like working out a complicated puzzle. But “a good match, that’s the truth about translation”, as David Bellos says in his Is That a Fish in Your Ear. Above all, I want to avoid making a translation that is simply correct, but without the texture and echoes of the original language.

MJ: Since both of the main characters—Solange and her love interest, Kouhouesso— are foreigners in Los Angeles, and Solange is a foreigner still while they’re filming in Cameroon, there are frequent mentions in the novel of certain things “happening in French,” or what it means when the two of them speak in English rather than in French. How did you decide to translate these moments into English (or use the French or Camfranglais) the way you did?

PH: In the beginning of the novel, in L.A., Solange is the typical French woman: “As for her, everyone knew she was French. She could work on her accent and play an American, but most of the time they wanted her to play a French woman: the shrill bitch, the elegant ice queen, the romantic victim…people often joked that, even from a satellite, you could tell she was French. Was it her figure? The angle of her jawline? Or the tic of starting sentences with a little sceptical pout? Apparently, languages shape faces. Her speech therapist in Los Angeles, with whom she practised accents, thought it was an issue of muscular tension.” But she can’t pick him: “At first she thought he was American. His intonation, the way he moved.” Just to confuse her, he turns out to be Canadian, born in Cameroon.

They discover that they both speak both French and English, and their rapport shifts depending on which language they are speaking:

“He hardly ever responded in French. Where he came from, they spoke English and French and numerous (three hundred!) other languages. Nous n’avions pas précisé une heure: the sentence was a bit odd, but mostly it was his accent that was odd. An accent like the comedian Michel Leeb’s. For a second, she thought he was making fun of her. That he was overdoing it. In her village, in Clèves, in the eighties, there was always someone imitating Michel Leeb imitating black people. If he had said in English, just as firmly, we didn’t say what time, she might have been intimidated. But she wanted to smile now…”

After they have sex for the first time, Solange muses: “It happened in English. Perhaps it would not have registered with such force in French. Well, how would she know?” When Solange gets angry with him, she speaks in French. There was, of course, no question of leaving this in French, but I chose to leave hints of the original in the text, just as Darriuessecq sprinkles her text with English.

With the locals in Africa, Kouhouesso speaks Cameroonian pidgin, Camfranglais. I located a Camfranglais dictionary—it was difficult but fun finding equivalent rhythms in English.

MJ: How would you compare translating Darrieussecq to other writers you’ve translated, such as the Nobel Prize-winner Patrick Modiano?

PH: Translating Max, a prize-winning young-adult novel by a French writer, Sarah Cohen-Scali was in some ways easier than translating Darrieuesscq’s novels. The prose is simpler, both in vocabulary and syntax, and there is none of the complex linguistic and metaphorical work to decipher. But Max is a child-narrator with a distinctive voice, shrill and monomanaical, as befitting a bigoted boy raised under the Lebensborn program, whom we follow from a foetus to the age of nine, completely indoctrinated by Nazi ideology until he meets a Jewish boy and the scales fall from his eyes. It was a challenge to enter into this persona and then capture and sustain the rhythms and idiomatic speech of a little punk whom we both deride and pity. I think it’s important not to fall into the trap of smoothing over the English translation when the original is sometimes awkward or unwieldy.

In translating Little Jewel by Patrick Modiano it was again a challenge to capture his pitch-perfect, deceptively simple style, often described as la petite musique. This is the only one of Modiano’s novels narrated by a female voice, but it is similar to his other novels in that the tone is haunting, yearning, hallucinatory, sometimes panic-stricken. The weight of the past, of guilt and the unknown evokes a resonance of secrets that may never be revealed. Whereas in translating the precision of tone in Men, I kept in mind Darrieussecq’s sense of an exploratory dismantling of language and of a world in order to reveal things afresh.

One of the problems I had to think my way through as I translated Little Jewel was how to deal with the way Modiano effortlessly changes tenses. His world is the past—from the perspective of the narrator and also, occasionally, of the author. While it might have been easier to smooth over Modiano’s tenses in English, this would have betrayed an effect of temporal dislocation by an author who creates a world where memories, real or invented, are more real than anything else. Moving between these different realms of the past is precisely what creates the genius of the Modiano style of flou, haziness, fragmentation, uncertainty. There are a few places in Little Jewel where I worried about the reader’s potential perceptions of these shifts in tense, but I chose to adhere to the original French and let the reader be brought up short, wondering whether the narrator is the author, and whether we are in the past or the present, a present that is taken up in the workings of memory itself.

I found it comparatively straightforward to translate Darrieussecq playing with tenses and time because it was more in terms of Solange’s deranged sense of time expanding and collapsing as she enters the state of obsessive waiting for her lover.

MJ: Are you working on any new translations at the moment?

PH: I’m finishing a translation of Marie Darrieussecq’s latest book, Being Here (Être ici est une splendeur), an unconventional biography of the German expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker. The book was published to coincide with a wonderful retrospective exhibition of her work at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris in May this year, for which Darrieussecq was one of the curators and she also wrote much of the accompanying catalogue text. In her characteristically elliptical, probing prose, Darrieussecq ignores the surface details of an ordinary biographical outline, focusing instead on the pressures Paula faced as a female painter at the turn of the twentieth century; on her original style and choice of subjects (she was the first to paint herself not only naked but pregnant); her friendship with the writer Rainer Maria Rilke; her fraught marriage; her ambivalence about combining her passion for her artistic career with motherhood; and her tragic death at thirty-one, soon after giving birth. Darrieussecq was inspired to write Being Here after seeing paintings by Paula Modersohn-Becker, of “real women” and “real babies”, depicted naked and in all the languorous physicality of pregnancy and breastfeeding.

And I’m looking forward to translating Marie Darrieussecq’s next novel (a few years off) in which, she has told me, Solange makes an appearance!

Penny Hueston is a Senior Editor at Text Publishing and a translator of novels, stories, articles, and poems, including works by Marie Darrieussecq and 2014 Nobel Prize winner, Patrick Modiano.

*****

Read More Translator Profiles: