Although considered one of the fastest-growing markets in the world, the Indian art market is still very much in its infancy. Painting dominates it. Artists are broadly divided into the “moderns”: the more mature “legacy” artists whom collectors feel more secure in buying, and the younger, more current “contemporary” artists, who push the boundaries of Indian art. There was not much of a market till the 1990s, when a more vibrant art scene emerged for established and younger artists alike. Since then, despite economic ups and downs, Indian artists and artists of Indian origin have been making their presence felt across the globe. And the world is paying attention, not just to India, but to artists from throughout South and Southeast Asia.

Growing up in India, I was initially attracted to the Indian portrait painters, especially the sumptuous portraits of a royal India, with the Maharajahs showing off their impossible jewels. Later, I was drawn to the more accessible colored photographs, hand colored over black-and-white prints, stiff but theatrical, with the textiles and jewels jumping off the images. There are the overwhelmingly opulent paintings of the 19th c. Raja Ravi Varma from the princely state of Travancore, who fused European academic art into Indian traditions. Then, there are the haunting self-portraits of a half-Indian, half-Hungarian Amrita Sher-Gil. Of the younger artists, the portraits by Surendran Nair, precursors to his more stylized flat narrative paintings, are so very powerful, as is the realism of Abir Karmakar. The digital portraits of Mahatma Gandhi by Aditya Pande push Indian portraiture into another arena entirely.

Today, a lot of the geographical and cultural boundaries have blurred. A young Pakistani artist Salman Toor lives between Lahore and New York City, and finds that he paints himself in a lot of the figures of his poetic canvases.

It was about ten years ago in New York City that I first saw images of paintings from a South Asian painter named Schandra Singh, who was clearly doing something different. I was struck by the powerful images and bold colors in her paintings, filled with an exuberant energy.

Unfortunately, I was late to her show. The gallerist told me there were no paintings left, save the title piece of the show, “Around and Around 1,000 Times,” which they had not hung and which was still at her studio. I drove out to Schandra’s studio in Poughkeepsie to see it. With the painting towering behind her, I met her for the first time. The “Singh” in Schandra Singh is unmistakably South Asian—the Sanskrit word for “Lion”—but the face didn’t fit the name. A contrast and complement to her work, she is delicate, petite, gentle, with blond hair that falls to her waist. I soon learned her mother is Austrian and her father Indian—though she identifies herself as an American. Our friendship has grown since.

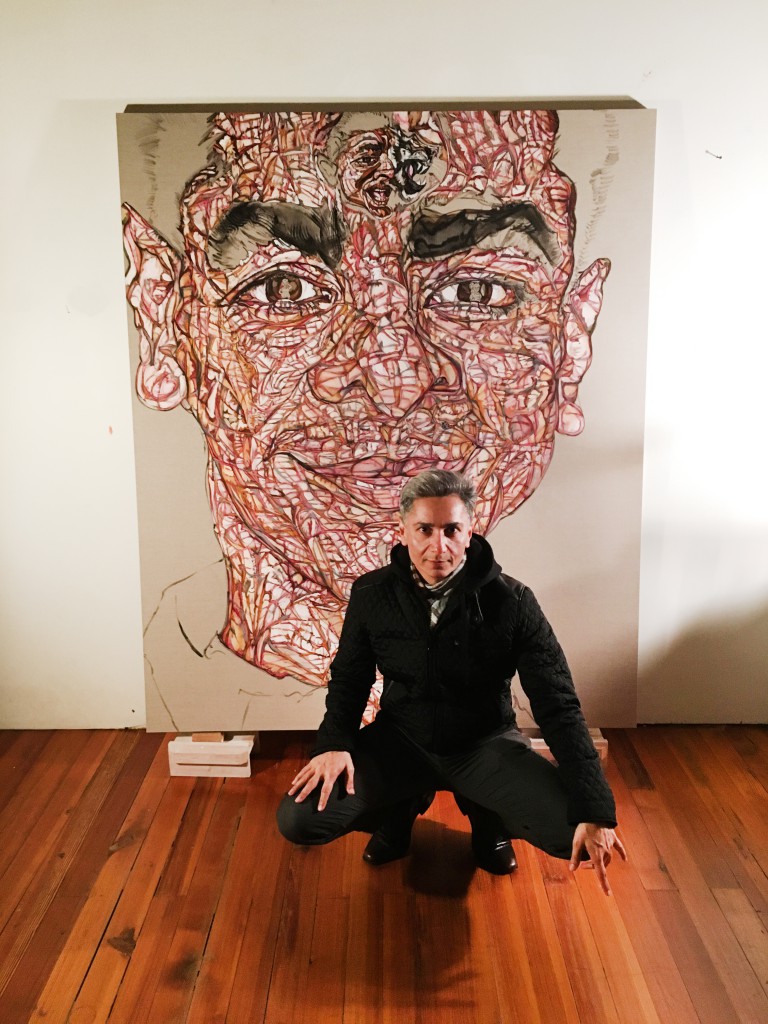

Today it is dusk, and I am driving home after another studio visit to Schandra, this time after viewing a new painting—a large portrait of “me.” I know I will need the hour and a half it will take me to get home to New York to get back into my own personal head space, after an afternoon in Schandra’s world. I was certain of this much going in: a portrait by Schandra would not be a flattering ego booster. I wasn’t sure what exactly it would be.

Though I had to know she would see me—all of me. Schandra is known for the totality of her representations, for surfacing the lightness together with the darkness, for pulling from life all that is complex, nuanced and contradictory. She expresses in her playful beach scenes shadows of the inevitable end to vacation, hints of ennui and forced fun, the distance of going on holiday only to realize you’ve brought yourself (and your problems) with you. Schandra came into her own as a painter in a postmillennial world—she watched the towers as they fell, as she escaped her apartment one block away on 9/11.

In the portrait of me, she breaks the frontal face into an explosive kaleidoscope of color, a fractured expressionism, filled with sensitivity and sensation—it feels both solid and fluid, in a way that at once brings the face to life. Compared to her other works, the portrait feels somehow simpler. It lacks the strong background color and “pop” elements which one is used to seeing in Schandra’s work. It is tranquil, more at peace—with a quiet, unshakable assuredness. Perhaps this is what makes the piece an outlier. It is different from her other works, where she expresses a kind of disharmony, a broken paradise, where vacationers travel to manmade utopias to seemingly “relax” or “unwind.”

On the first day of 2016, a few weeks after I saw my portrait for the first time, we met at a Gramercy Park restaurant.

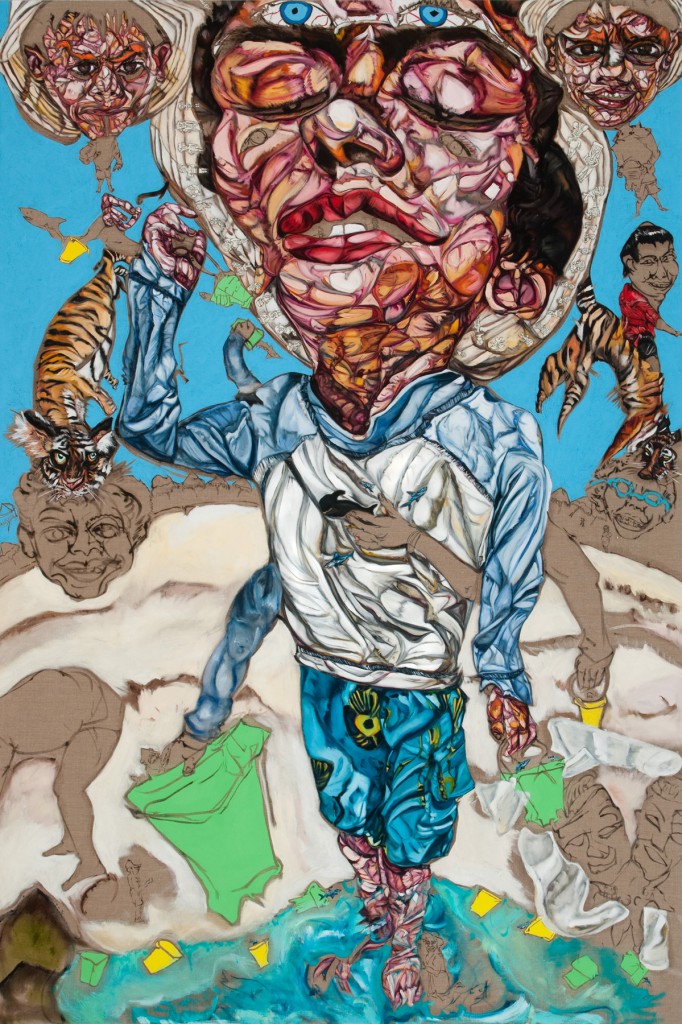

Shiva. Oil on linen.

Shaill Jhaveri (SJ): Let’s get the important things out of the way first. What is your favorite go-to dish, your comfort food?

Schandra Singh (SS): Fish. I like to cook fish with rice, and a salad. Or a channa-masala I learned to make that from my dad at the age of ten. He rarely cooks, but can throw together some yogurt, onions and chick-peas like nobody else.

SJ: Is there a go-to author or book?

SS: Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov changed my life. A friend suggested it to me in my freshman year at Rhode Island School of Design and I read it like a bible. I wrote in it like it was a diary. He delves into every aspect of the human soul in a way that gets under your skin—in an abstract unconscious way, that only painting can do for me.

SJ: Do you still read it?

SS: Yes. I still read it, but for a long time I couldn’t read the copy that I had written in. After 9/11, I was given a few minutes to go into my apartment and grab what I wanted. I lived a block away from Tower 2. My parents suggested I make a list of five things I should take out, so I would stay focused. At the last minute, I grabbed a sixth—the Dostoevsky book covered in debris.

SJ: Does that period inform your artwork today? Are you comfortable talking about it?

SS: It’s ok to talk about it. I was 24 years old and I woke up one morning to a war. I lost a part of my innocence that day. The color of the sky changed for me. I did a painting that dealt with September 11th about a year after the events. It was like a Rosetta Stone that unlocked a lot of my emotions from that experience. It is a quiet work. Unlike my current paintings, which to me at times feel more like explosions

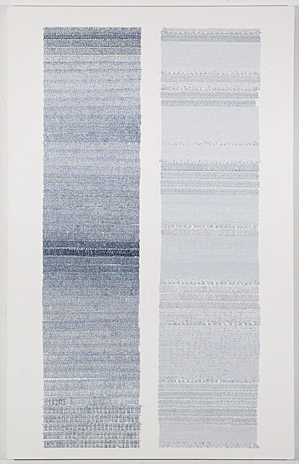

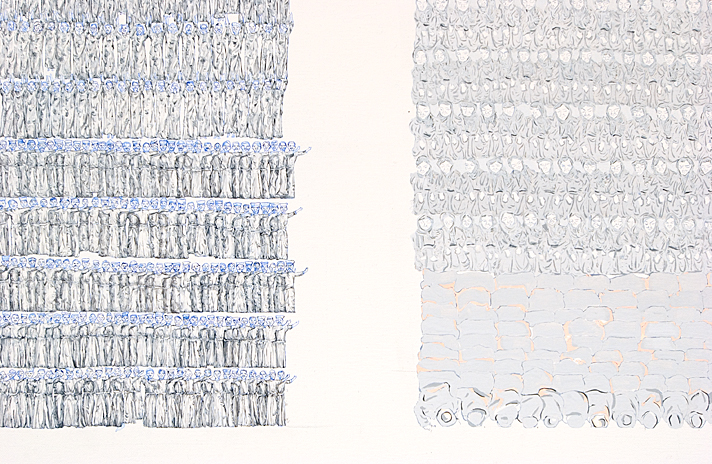

World Trade Center. Oil on gouache on canvas.

SJ: When I visited your studio for the first time, I recall seeing this very moving painting you are talking about of the Twin Towers. Can you tell me about it?

On the morning of September 11th, I had an 8 x3 foot blank canvas on an easel in my apartment. Nearly everything in my apartment got destroyed during 9/11—however this canvas remained miraculously unscathed. When I would go down to my apartment at Ground Zero to gather things, I would think: “I have to paint something on it.” Eventually I took the canvas, cleaned it up and did the “Untitled” painting.

The right side of the painting is made up of a pattern of Muslims praying while the left side consists of every person I could gather who was killed on that day, totaling 2,915 victims. Each person on the left side is documented by their name and number, so if you lost someone on that day you can find them in the painting. The left side is also categorized: the policeman and fireman are together, the victims from the planes including the one from Shanksville, the Pentagon victims, and so on.

SJ: What does this painting mean to you today?

SS: It’s interesting because the painting’s meaning seems to be expanding. I wanted the work to ask a question, not just be a memorial. That is why there is a Muslim side—I wanted the work to be open to interpretation by the viewer.

To me the Muslim side represents the innocence that was lost after September 11th, because of the evil of a few. I could gather the images of everyone who passed away on that day, but I couldn’t do that for the other side—and there is another side.

We still live with the fear of terrorism and unfortunately cast others in the shadow of that fear.

SJ: What had happened to you that day?

I had awoken earlier that morning to a beautiful blue sky, and fallen back to sleep. The phone rang constantly, and I awoke a little later to an overcast sky— the first tower had been hit. When I looked at my window things were falling from the sky, like out of a science fiction movie. I was underneath tower two when it fell. In my escape, I recall clearly thinking I was dead. Life was over so quickly. We couldn’t breathe, we couldn’t see, our eyes were burning.

[Note: Schandra later texted to tell me that she saw people jumping from the tower, but it was too hard for her to tell me that in person. She shared the details of a miraculous and harrowing escape.]

World Trade Center, detail.

SJ: Does that period inform your art work today?

My mark changed after that day, no doubt. But I feel my work is about a façade—feeling one way but looking another. The events of September 11th changed the world, but it was also my own personal story. Everyone has a story where some part of them changes where they question the color of the sky.

SJ: Before September 11th were you an artist? How did you start painting? Why?

SS: During a mandatory art class in high school, the art teacher called my mother in for a private talk. My mother thought I had done something wrong. She told her that in everything I did, there was something “off,” but in a good way. Soon after that, before a family trip to Europe my mother bought me a box of “Cray-Pas” and a sketchbook. I was 15. I drew throughout the trip, but hid the drawings, because they were so different. I didn’t try to make anything perfect or good. They were abstract, they were my diary, my subconscious. That same year I went to MOMA and saw a Matisse retrospective. I didn’t know who he was and went alone. From the first painting he made to his cutouts, Matisse showed me that my art was not imperfect. I realized that the passion I had been hiding had a place in this world.

SJ: It’s interesting that you started drawing in Europe. Does your European heritage influence you?

SS: Yes. My mother is Austrian. Austria and Germany have a long history of exploring the human soul and our subconscious in art and literature. Look at Freud, Egon Schiele, Herman Hesse and the German Expressionists like Otto Dix or George Grosz. They all explore existentialism. I think I share this affinity with them in my work.

SJ: Let’s get to the portrait of me that you have just finished. Have you ever painted someone you know before?

SS: There is a very small caricature of a girl in a bikini in the background of “The Lazy River” painting. That was my sister. There is the back of my mother in another painting, “The White Suit.” But no, I usually don’t paint people I know. This is a first. When you paint someone you know, you are aware of them more. You don’t want to be unflattering to someone you care about, and I know my work can appear unflattering. The work is not about the person, it’s my personal vision. They are vessels for my ideas and my emotions. And when you paint someone you know, that can shift a little. It can be too loaded to go in there and paint freely. That was the challenge in painting you. It was a huge challenge.

Shaill Jhaveri with Schandra Singh’s portrait of him.

SJ: How did you get to what’s on the canvas now?

SS: I had just come back from India, after not having been there since I was a young girl. Seeing India after so many years and painting my Indian friend seemed like the right thing to do. I had so many ideas for this painting, and India was going to be very apparent in the work. But ultimately I didn’t go there. India is this place where the colors are so vibrant, but there is a darkness to it. I don’t think the darkness came into this painting. The way I make a mark is very loaded, and India is very loaded. It is over-stimulating, heartbreaking and beautiful. It’s like falling in love and having your heart broken every day. This painting is still about India, a peaceful India. Except for the tiger in your forehead! But the two little girls in your eyes are the contrast to the tiger, the innocence. The Yin to the tiger’s Yang. You cannot have one without the other.

SJ: Tell me about the two little girls in my eyes.

SS: I was at the Amber Fort in Jaipur, and this beautiful little Indian girl of about 3 or 4 was elevated and posing for her parents. She wore a pink dress, with white stockings and white shoes.

SJ: I asked you about your European side, but can you tell me anything more about how you connect with your work and your Indian heritage?

SS: I sometimes say the Indian miniature painter comes through in my work. But after being in India, I know it is also about the color. The colors of India are so vibrant, but there is a dusting over this vibrancy. My colors are poppy and brilliant, but because I paint on linen, it is like a pop of color in the middle of a desert. Like a woman’s sari on the road to Rajasthan.

SJ: There is your characteristic use of unpainted brown linen peeking throughout the painting, both in the face and the background.

SS: It is a game of space. If you look closely, throughout the face there are moments that are just linen—if you put paint on that moment, the painting falls apart. The empty spaces keep the face alive.

SJ: Is this painting different than others you’ve done?

SS: In so many ways. For one, it had no deadline, and was not for a show. Because of this something happened in the mark making, the fluidity. I was also using a digital image for the first time. For such an intimate portrait, I wasn’t sure if I could read the face. I usually only work with images from film. And then, I was painting someone I know. I was scared to show it to you. I wondered if you would like it, if you would think it was done. It was finished weeks before I had the courage to send you the image.

SJ: And now that I’ve seen it…

SS: I don’t want to give it to you! I like it so much in my studio since I see you smiling at me. You are my little piece of peace in the world.

Schandra Singh‘s paintings were featured in the exhibition “The Silk Road” shown by the Saatchi Gallery at Lille 3000 in Lille France. Singh’s paintings were also featured at the Saatchi Gallery London in the show “The Empire Strikes Back”. Her solo shows include the spring exhibition at Bose Pacia Gallery, New York, Galerie Sebastein Bertrand in Geneva, Switzerland and a solo show with Nature Morte Berlin, Germany in 2011. She also showed her work at MOCA Shanghai in “India Xianzai”. Singh’s painting about 9/11 ‘Untitled’ will soon be on view at the National September 11th Memorial Museum at Ground Zero in New York.

Jewelry designer Shaill Jhaveri was born in Mumbai, India and was awarded a design scholarship from Tiffany and Co. at the Parsons School of Design. He lives in New York City and his jewelry is in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

*****

Read More Interviews: