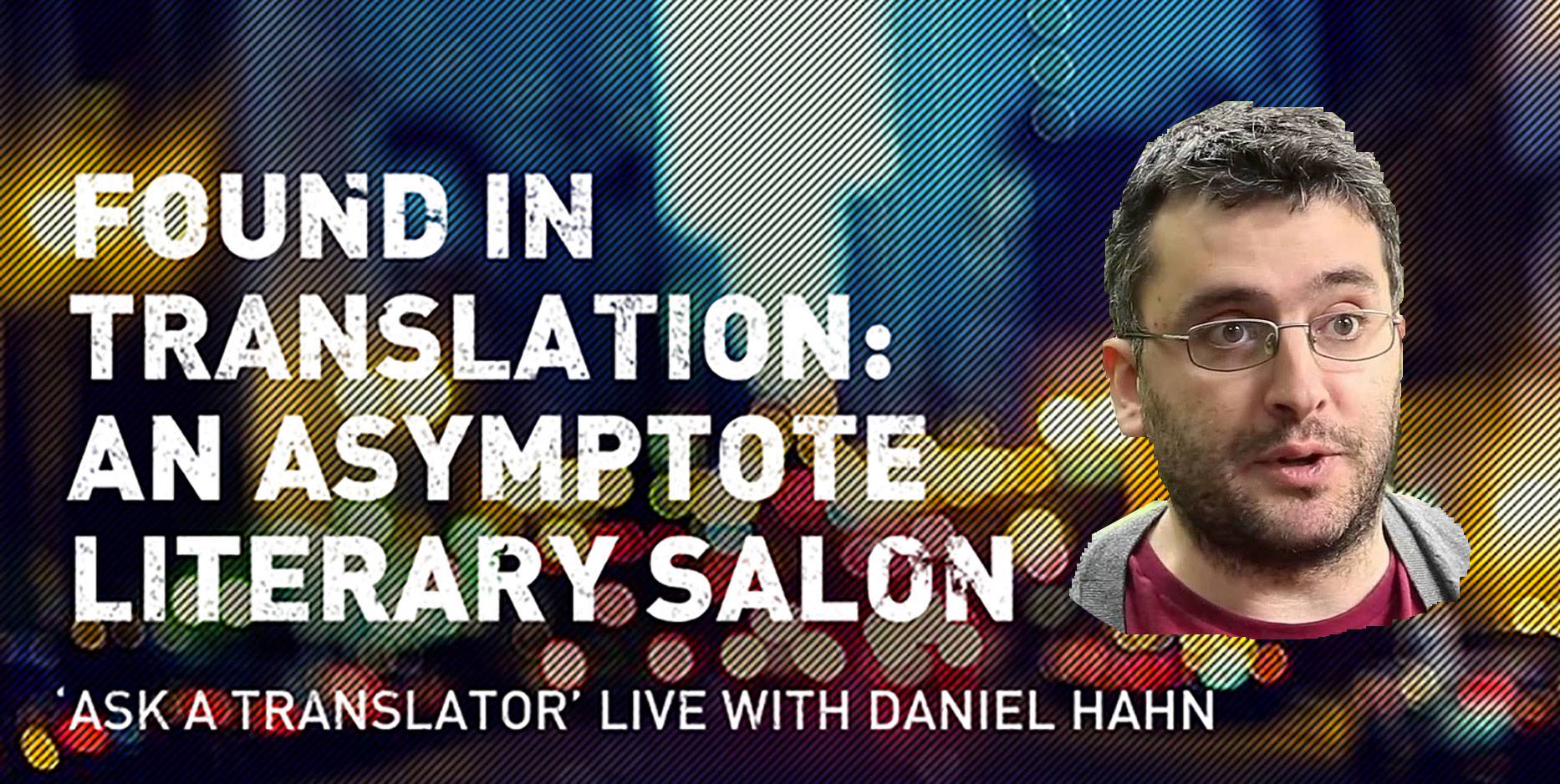

Since we launched our ‘Ask A Translator’ column last December, award-winning writer, editor and translator Daniel Hahn has been on hand to remedy the translation woes of Asymptote readers around the globe. Given the overwhelming love that our readers show for the column and Daniel (seriously, you guys are the best), we can’t wait to welcome Asymptote fans to our very first literary salon today at Waterstones Piccadilly, London on July 20th. The event will be hosted by our Editor-at-Large, Megan Bradshaw and will see Daniel fielding questions from the audience and our readers via Twitter. You can find out more about the event and reserve your place here, or if you can’t attend the event, tweet us your translation question with #AskATranslator.

In anticipation of the event, we’ve put together a shortlist of the six most important lessons for aspiring translators:

- Don’t be starstruck by authors (and don’t be afraid to stand your ground)

“Imagine approaching pretty much any writer and saying, “Look, here’s the plan, we’re going to change lots of things in your book—no, I really mean lots of things, like all the words—then we’re going to publish it all over the world in your name, but you won’t get to see what it actually says… Sound OK?” They’d be within their rights to feel more than a little uneasy about it.

[…]

But just as I don’t always understand what they’re doing, they don’t always understand what I’m doing either. And their English is sometimes not quite as good as they think it is. (Or at least I hope it’s typically less good than mine, otherwise I might as well pack the whole thing in.) While I want them to be reassured, I’m the person who signs things off for the publisher, and I have to be happy with the English text—my name’s on it, too, and if something sounds funny that will end up being my fault.”

- Be bold, be ambitious and, above all, don’t worry about the competition

“You can assess a translation—like any work of art—by its achievement of success in its own terms, how it manages what it’s set out to do. You can evaluate, too, whether you think that’s a thing worth doing at all. But the decision as to which of two translations is superior assumes they share the same goals. To take a crudely exaggerated example—say you’re trying to compare King Lear, the Sistine Chapel ceiling and chocolate ice cream. Which is better? Impossible to say.”

Now, when a publisher commissions me to translate a novel, I do work under the pretence that I’m writing not a translation but the translation. That’s the pretence, and aspiration…”

- Make sure everything is in your contract (and avoid nasty surprises)

“Get a contract. Make sure it’s unambiguous. Make sure it’s comprehensive. Make sure you understand it. Make sure you can comply with your part of the bargain. Oh, and don’t start work till you’ve got it.

If you know, going in, what standard the publishers expect of your work, what kind of editing will happen to it, what input you’ll have at copy-edit and proof stage and so on, you won’t be affronted at the very idea that someone might have the gall to suggest improvements to your precious commas, and your publisher will know they have to run things by you. “

- Translation is about learning to fail better, not perfectionism

“Translation is all failure, because it’s never “perfect”; and it is all also, simultaneously, a triumph, because however imperfectly something living has been created out of the most unlikely circumstances.

Now, I used the word perfect. But I used it rather nervously, and in “scare quotes” to protect myself, because I don’t know what it means, I don’t know what perfection in a translation would even look like. My aim when translating isn’t perfection, my aim is to use English to make a piece of writing that does the same things another writer has done before me in some other language; my aim is to take one superb piece of writing, and make another superb piece of writing that can stand in for it with a new set of readers.”

- Work to your strengths (but don’t be afraid to broaden your horizons either)

“If at all possible, only translate the kind of books that you feel able to understand. Don’t pretend to be a crime fiction expert if you don’t read crime fiction yourself, if you have no grasp of its habits or simply don’t understand how the language of a crime novel works. Different genres use stylised language in different ways. So if your job is to write one of these books in English, how can you plausibly write one if you don’t read them?

But also…

If at all possible, translate all kinds of books, whether they’re to your usual taste or not. If you’re going to be a professional in this business, and not just a hobbyist, you probably won’t be able to afford only ever to translate your absolute favourite writers; and even if you fancy yourself as utterly, incorruptibly, vertiginously highbrow, you should try throwing yourself into a fun, pacey detective novel from time to time. Seriously, get over yourself.”

- Remember: the translator, above all else, is a force for good

“It would obviously be grandiose and, well, silly to suggest that something as marginal as literary translation can fix all the big problems, heal the world, peace and love, everyone . . . But I do believe in the great, activist, essential good-ness of the beliefs underlying it.

The work of translators—like it or not—brings people together, and to my way of thinking that is A Good Thing. And translation doesn’t merely demand a belief in honesty and generosity and empathy, it’s a symptom of those things, too. “

*****

Read More Ask A Translator: