Like all Chileans, Crabby spoke in a singsong way, her voice vibrating in her nose. She laughed at everything, even celebrity deaths, and made cruel jokes. She drank red wine until she collapsed in snores, only to wake up barefoot because someone had stolen her shoes. She ate empanadas and sea urchin tongues in green sauce seasoned with fresh, extra-hot chili. Whenever the cops beat a “political agitator” to death, she turned a blind eye, pretending not to notice. Actually she wasn’t Chilean but Lithuanian.

She landed in Valparaíso when she was two, pulled along by her mother, a fat redhead who spoke only Yiddish, and her father a tall (almost seven-foot), skinny fellow as light on his feet as a bird. His profession was the most pedestrian imaginable: callus remover. Using prayer, he made the calluses on people’s feet fall off. Since his name was Abraham and his wife’s name was Sarah, he dreamed—for too many years—of having a son he could name Isaac, which in Hebrew means, “he laughs.” After anguished efforts, ten months of gestation, anemia, forceps, a cesarean, a strangling umbilical chord, Sarah finally gave birth to a daughter. Abraham stubbornly insisted on naming her Isaac, but very early in life, even before she began to walk, the girl would burst into an angry fit of wailing the instant she heard that persistent “Isaac.” Only a teaspoon of honey would calm her down.

Intelligent, she could read by the age of four. She rejected the Ladino translation of the Torah, so her first book was Paul Féval’s The Hunchback. She so adored the character Henri de Lagardère that she began to walk hunched over, her legs spread, the tips of her shoes pointing in opposite directions, and her arms bent at right angles. No one bothered to correct her posture. The only thing they did manage to do was nickname her “Crabby.” She tossed out “Isaac,” which would have destined her to suffering the world’s laughter, and instead identified with her nickname, accepting the idea of being an aggressive crab separated from others by a hard shell.

By the time she was eleven, she’d broken a dozen classmates’ noses, so no school would accept her. Between his murderous chanting away of calluses and his davening in the synagogue, Abraham had no time to worry over his daughter’s education. Crabby’s school was the street. She learned a series of professions, among others: re-selling cheap watches for three times their original price under the pretext that they were stolen, painting the hooves of the horses used by funeral parlors black, washing and combing the dogs of high-class prostitutes, and manufacturing “smuggled whiskey” out of tea, crude sugar, and drugstore alcohol. When she was thirteen, she lost her father and menstruated for the first time. She mounted his unvarnished wood coffin as if it were a horse and rode along, staining it red. Sarah, seconded by her instantaneous new husband, kicked her out of the house.

Crabby, her face transformed into a bitter mask, set out on a tour of Chile, a country as long, thin, and foreign as her father. She ended up in the north, in Iquique, a bone-dry port, where the workers in the nitrate and copper mines would come down from the mountains to spend their weekly salary without noticing the rotten dog stench that poured out of the fishmeal plants and infected the streets. Crabby began to work as a maid in the Spanish Club, an “Arabian-style” building designed by an architect whose only knowledge of Islam came from the illustrations in the expurgated nineteenth-century French translation of The Thousand and One Nights. Since her hunchback gait upset the members’ stomachs, the management dispatched her to the lavatories. After a year, she began to sprout a beard. Unwilling to obey the requests of the Aragonese manager, she refused to shave. When the requests were accompanied by grimaces of disgust and insults, Crabby presented her resignation in the form of a punch that sent the brash Aragonese rolling down the stairs. She also beat up two waiters who had the misguided idea of avenging the manager, who lay on the Churrigueresque tile floor howling in pain from some broken ribs. While working in the lavatory, she had made and saved money selling the honorable members cocaine cut with talcum powder. She used her capital to set up a shop for buying and selling gold. She also became the local dentist. After the drunken miners had spent all they’d earned in six months on a weekend orgy, they would line up outside her little shop insisting on selling her the gold crowns that adorned their teeth so that they could go on drinking.

Two years went by, two years of drought. Then, suddenly, the mountains awakened wearing clouds for hats. The sky turned black, thunder roared, lightning flashed, and a deluge commenced with raindrops the size of pigeon eggs. The tempest went on for three days without stopping. No one could go out because the drops were so forceful they punched holes in umbrellas. Locked away in her shop, in the semi-darkness, with no more beer to drink, Crabby suddenly, and for the first time in her life, realized she was alone.

The skeleton of her solitude appeared before her: impersonal, heavy, and cold. And then she saw flesh gather around those bones, forming a body for which she felt not the slightest tenderness. It reacted to her disdain by tightening itself around her from her stomach to her throat to deliver her a dull, constant pain. It was like having her soul pierced by a nail, in the depths of a world transformed into jelly, where she was sentenced to drown for all eternity. “Who am I? Can someone tell me? How could they, since no one has ever seen me? It hurts, it hurts! I am a wound awaiting the gaze of another in order to heal. A frog who will never turn into a princess. A freak, who when she wants to give, only gives the gift of disgust. The world’s indifference is my punishment!” She clung to the wall, sliding left and right, absorbing the darkness of the place through every pore until she felt she was black, a shadow that wanted to cry like a dog in the absence of a body to master it.

The drops exploded noisily on the tin roof. Nevertheless, a scream, so high-pitched that it became a long needle, pierced the rain’s atrocious drumming. Only a completely feminine throat could howl like that. Crabby, not knowing why, felt herself the mother of that female under threat of death and, waving the iron bar she used to frighten off hostile drunks, ran out onto the street.

A mantle of gray mist hid the sky, forming thick folds. In the distance, a pale phantom began to take shape. It came toward her, running, a woman with extremely white skin, as white as flour, salt, marble, a shroud, or milk. It passed through the wall of water and fell into Crabby’s arms, shaking like a wounded albatross. It was as tall as her father, with powerful legs and buttocks and enormous breasts; she was very young, but her mad blinking revealed, beneath white eyelids, the pink irises of an old woman. The howling wind tangled her long white hair, baring a shoulder that had received a deep bite. Sniffing excitedly, foaming at the mouth, growling, three Asiatic monks wearing saffron robes ran toward them. The white woman hid behind Crabby’s back, using her as a shield.

Crabby whirled the iron bar. “Hold it right there, you fucking Chinamen! One more step, and I’ll smash your skulls.” The monks stopped for an instant, never taking their eyes off the marmoreal flesh the skinny body of her defender could not hide. Then they revealed the hands they’d been hiding in their sleeves. Thirty long fingernails, as sharp as knives, whistled menacingly. Crabby, unable to stop the attack, smacked her bar on the street: “May the devil swallow them!” With a colossal roar, the earth obeyed. A crack opened, and the mad creatures fell howling into the abyss. The enormous maw, now satisfied, closed. The rain stopped, the sun came out, ready to reign for another couple of years, and to celebrate the return of light, thousands of small parrots, forming a multicolored cloud, chorusing syllables Crabby interpreted as “Albina, Albina, Albina…”

The enormous woman, expressing her gratitude in infantile sobs, gave no sign of leaving. There seemed to be no other place in the world for her but Crabby’s arms and bosom. Crabby led her into the shop, sat her down in the armchair, and, with a tenderness never before seen in her, began to clean out the bite.

Translated from the Spanish by Alfred MacAdam

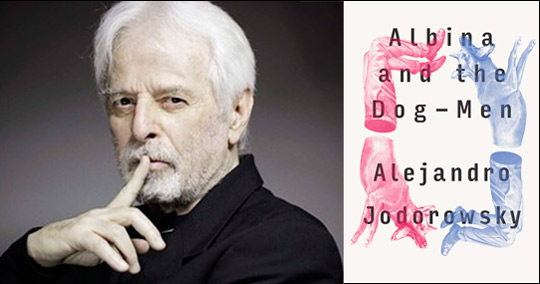

Albina and the Dog-Men hits the bookstores today. Find out more about the book here.

*****

Alejandro Jodorowsky was born to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants in Tocopilla, Chile. From an early age, he became interested in mime and theater; at the age of twenty-three, he left for Paris to pursue the arts, and has lived there ever since. A friend and companion of Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor, he founded the Panic movement and has directed several classic films of this style, including The Holy Mountain, El Topo, and Santa Sangre. A mime artist, specialist in the art of tarot, and prolific author, he has written novels, poetry, short stories, essays, and over thirty successful comic books, working with such highly regarded comic book artists as Moebius and Bess. Restless Books will be publishing three of Jodorowsky’s best-known books for the first time in English: Donde mejor canta un pájaro (Where the Bird Sings Best), El niño del jueves negro (The Son of Black Thursday), and Albina y los hombres perro (Albina and the Dog-Men).

Alfred MacAdam is professor of Latin American literature at Barnard College-Columbia University. He has translated works by Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, Juan Carlos Onetti, José Donoso, and Jorge Volpi among others. He recently published an essay on the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa included in The Cambridge Companion to Autobiography.

Read more from Translation Tuesday: