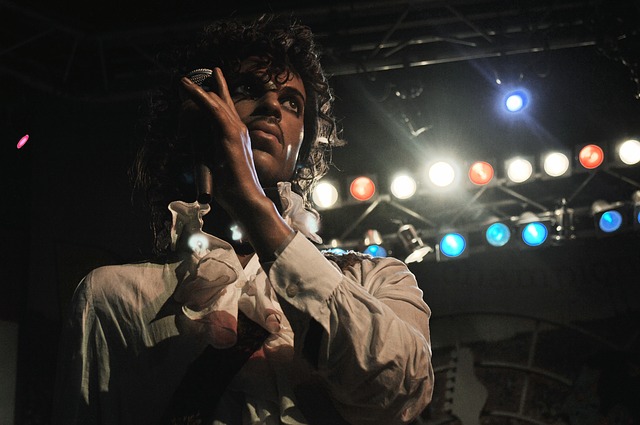

In the same manner that African Americans were forced to create the only original American language, Black English, Prince is a prime example of the creation of a new form, through amalgamation, which evolves from a need to survive. In his article “The Musical Alchemist,” Luis Hidalo states that what sets Prince apart is “his influences, his musical inspirations, the ease with which he assimilates them and then reinvents them with his own personal imprint. Prince has created his own unique style… an incomparable way of making music, a style you can distinguish by the second verse.”

What are Prince’s accomplishments? What did he achieve? First and foremost, his individual freedom. Second, being an encyclopedia of American Music, to paraphrase music critic Nelson George, Prince simultaneously continued the legacy of the African American tradition of Little Richard, Chuck Berry, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye, Sly Stone, Maurice White, and Parliament Funkadelic while adding to its narrative the discourse of the post-Civil Rights (which is something completely different than post-racial) African American grappling with place and space in a world of hopes, new opportunities, and continued racial limitations. While Prince was not interested in denying his blackness, per se, he was definitely interested in pondering ways in which he could discuss blackness on his own terms. Next, Prince takes a page from the punk-rock movement of the late seventies and early eighties and fashions what almost becomes a category of alternative music for African Americans. Without this, there would be no Lenny Kravitz, no Terrence Trent D’Arby, no Toni, Tony, Tone, no Me’Shell NdegeOcello, no D’Angelo, no Fishbone, no Living Color, and no Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, at least not in the manner in which we think of them and the manner in which they create and present music. Thirdly, Prince was one of the lone voices of the eighties who wanted ownership, continuing the legacy of Stevie Wonder and passing it on to Jam and Lewis, L.A. Reid and Babyface and Master P. Paisley Park Records attempted to be a real player in the game, signing new acts as well as working with established acts such as George Clinton, Mavis Staples, Miles Davis and Patti LaBelle. Fourth, his work with drum machines and synthesizers expanded on the work of Wonder and revolutionized the technology used in Hip Hop, paving the way for producers such as Dallas Austin, one of the first super-producers of Hip Hop. Austin affirms Prince’s importance and influence on all who follow him by stating, “He’s my total influence in production and songwriting.”

A company actually gave Prince the prototype for a new drum machine to test, and the result is a lot of what you hear on 1999. It is this work with drum machines that drove early hip-hop grooves. His work in the technological aspect of making the artist completely self-sufficient is so ahead of the curve that Wonder prefers to record at Paisley Park when he is in the mid-west, foregoing the studios in Chicago, Detroit or Philadelphia. Fifth, his use of guitar riffs over and underneath big, heavy handed beats and bass lines pushed the work of Hendrix and Ernie Isley into the nineties so that he is the bridge between Hendrix and Isley to D’Angelo and Wycliffe Jean, especially their use of guitars as haunting landscape. Sixth, Prince, by staying true to his vision, helped to redefine a generation’s notion of reality, truth and success. Selling 100,000 copies is a success if you own the record label and get the “lion’s share” of the profits. One is only emancipated if one defines the terms of his freedom. Prince has been defining himself, his vision and his goals since day one. Finally, his use of the sex metaphor sets him apart from the lyricists of his time.

Prince used all of the interest, concerns and anxieties connected with sex to present a higher message that we are all looking for love and go down many roads trying to find love, with sex and drugs being the major mis-guided roads. This puts Prince in his rightful place of being a poet. Prince kept alive the African American tradition of lyrical poetry throughout the eighties as a storyteller and a man grappling with his place and identity. In this sense, he is a griot, even if not in the strictest African connotation. He is a griot in that he is a soothsayer, a teller of stories and a voice for his times, attempting to plot that voice along the line of culture, change and history.

Prince was perceived by many black fans as coming home too late and commenting too long on metaphysical issues and not on physical issues. For them, Prince moved from identity issues to spiritual issues without keeping his ear to the streets enough to balance his own artistic search with the search of the music patrons. This is where he, as many others, has fallen prey to what Maulana Karenga called “a useless isolation” and “a false independence.” Finally, he has gone the way of the tragic mulatto in African American literature. He is now alienated because of the rise in Black Nationalism brought on by the Reagan/Bush Administrations and the rise of Hip Hop, which is the popular culture’s reaction to Reaganomics and conservatism.

The video age has produced a generation of young folk who want someone who looks like them. Prince does not. It becomes easier for young black artists who look a certain way and lace their work with signature Prince riffs, beats and lyrical imagery but still stay in the norm of the current African American trends. He is also alienated from those white kids of the eighties who grew up to become conservatives or pseudo-liberals. Moreso, he has become the victim of white radio stations and white music critics who have sought to create a category for white rockers who often complain about not being able to sell records because of whatever the latest black revolution in music is. Prince, himself, affirms this in his song “Don’t Play Me” when he states: “Don’t play me. I’m the wrong color, and I play guitar.” Still another obstacle contributing to Prince’s absence from the charts has been his choice of singles from his albums. Every Prince album is a musical dichotomy because they all include signature Prince tunes as well as tunes which have been influenced by the current trends.

With the exception of Hip Hop, Prince has been able to amalgamate new sounds into his own repertoire fairly well and easily. However, the singles he generally releases are songs that are not in the vein of what is happening on the radio. Artistically, that is not an issue of right or wrong, good or bad. Economically, on the other hand, one has to wonder why he goes through so much trouble staying current, evolving and then leaving those tunes buried on the album. He has, himself, admitted that staying current is important to him. He asserts, “It’s always a struggle balancing what worked in the past with what is happening now.” There, then, seems to be some internal struggle within Prince of not being able to balance his need to do and prove that he can do anything and, at the same time, follow his own, unique vision. This, again, is not an issue of good or a bad, but merely points to an artist always struggling with vision, growth, and identity. Finally, Prince’s need to get his own vision across has also alienated him because of his reluctance to work with the industry’s chosen new powers, especially rappers. And when he has worked with young talent, it as seemed as too contrived or as a last ditch effort to save a fading career.

Yet it should also be noted that Prince has a history of periodically replacing older members of his band with new and younger members so that he will continue to grow musically. Even with his perceived alienation, Prince remains one of the most respected figures in the business by those who came before him and by those who follow him. Little Richard proclaims him as “the genius of his generation.” Eric Clapton states that “He is the master of everything. To see Prince on the screen, singing ‘Purple Rain’ was the reaffirmation of why I got into the music industry.” Quincy Jones applauds his determination to constantly grow and achieve. “He’s bold with a lot of guts. That’s the one thing that I like about him. He’s constantly searching and trying to grow and grapple with what his future is about.” Miles Davis also affirms Prince’s wide range, diversity and growth. “He plays piano. Plays the drums, the bass, the guitar, plus he can dance, and he never, never misses. He’s changing, you kno’? What I mean is every time I hear him it’s a little bit different.” L. L. Cool J also understands his importance. “His longevity is a testament to his creativity. I respect him as an artist. I respect his music.” Even the hard-hitting, Hip Hop icon Questlove, who never pulls his punches, sees Prince as both a bridge and major influence on the present generation.

From the release of The Rainbow Children in 2001 to “Baltimore” in 2015, Prince’s art shows that he was able to balance his desire for personal liberation with the tangible/material struggle of the socio-politically oppressed, especially African Americans. That creation and balance may not have always been popular or seamless, but it was always powerful and influential, like the night he set Twitter ablaze when at the 2015 Grammys he stated, “Like books and black lives, albums still matter.” From day one until the end, Prince was committed to using his art and life to push the buttons that forced us to think about who we are and where we stand. None of this is, of course, new. Prince is just another step in the ladder of musical evolution. But he is important because he fought against the pressures of being made a monolith or one dimensional because of his race. More than a flash in the pan, Prince was one of the few who actually helped to mold the pan. To quote his song “Thieves in the Temple” you can still hear his “voice beating in the chest” of American music. He has done too much to be forgotten.

Bibliography:

Cortez, Jayne. “How Long Has Trane Been Gone.” The Norton Anthology of African

American Literature. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1997.

Davis, Miles. Miles: The Autobiography. New York: Simon & Simon, 1990.

Dubois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folks. New York: Gramercy Books, 1994.

Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. It’s New York: Vintage, 1995.

Fudger, David, ed. Prince in His Own Words. New York: Omnibus Press, 1984,

George, Nelson. “Interview.” The Prince of Paisley Park. Omnibus. London. BBC Television. 1991.

Hazzard-Donald, Katrina. Jooki’: The Rise of Social Dance Formations in African-American Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992.

Hill, Dave. Prince: A Pop Life. London: Faber and Faber, 1989. (New York: Harmony, 1989.)

Hughes, Langston. “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1997.

Jackson, Michael. Thriller. Epic/Sony, 1982.

Karenga, Maulana. “Black Art: Mute Matter Given Force and Function.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1997.

Questlove. “Someday Our Prince Will Come?!!?” Rap Pages. April, 1997. (Reprinted in The Prince Family. Vol. 5, Issue 18. August 30, 1997: 106).

Walker, Margaret. Jubilee. New York: Mariner Books, 1999.

Welsing, Francis Cress. The Isis Papers. Chicago: Third World Press, 1991.

Wonder, Stevie. Songs in the Key of Life. Taurus/Motown, 1976.

Woodson, Carter G. The Miseducation of the Negro. Trenton: Africa World Press,1990, 1998,

Wright, Richard. “Blueprint for Negro Writing.” The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1997.

*****

C. Liegh McInnis is the author of seven books, including four collections of poetry, one collection of short stories, and The Lyrics of Prince: A Literary Look at a Creative, Musical Poet, Philosopher, and Storyteller. He is also the former editor/publisher of Black Magnolias Literary Journal and an instructor of English at Jackson State University. For more information, go to www.psychedelicliterature.com.