In December 2015, my new play, The Silent Whip, premiered on the small stage of the National Theatre in Bratislava. It was written as a warning about what might happen if my country, Slovakia, fails to come to terms with its wartime past, but in light of the recent general election there, which has swept a neo-Nazi party into parliament, it turned out to be a grim prediction.

My country’s history is marked by a recurrent loss of memory, mostly imposed from above. As someone who spent nearly half of my life under state socialism, with history lessons filled with blank pages and distortions, I have found history to be a never-ending fount of fascination and explored it through my writing, much of which is based on real figures from our more distant and recent history.

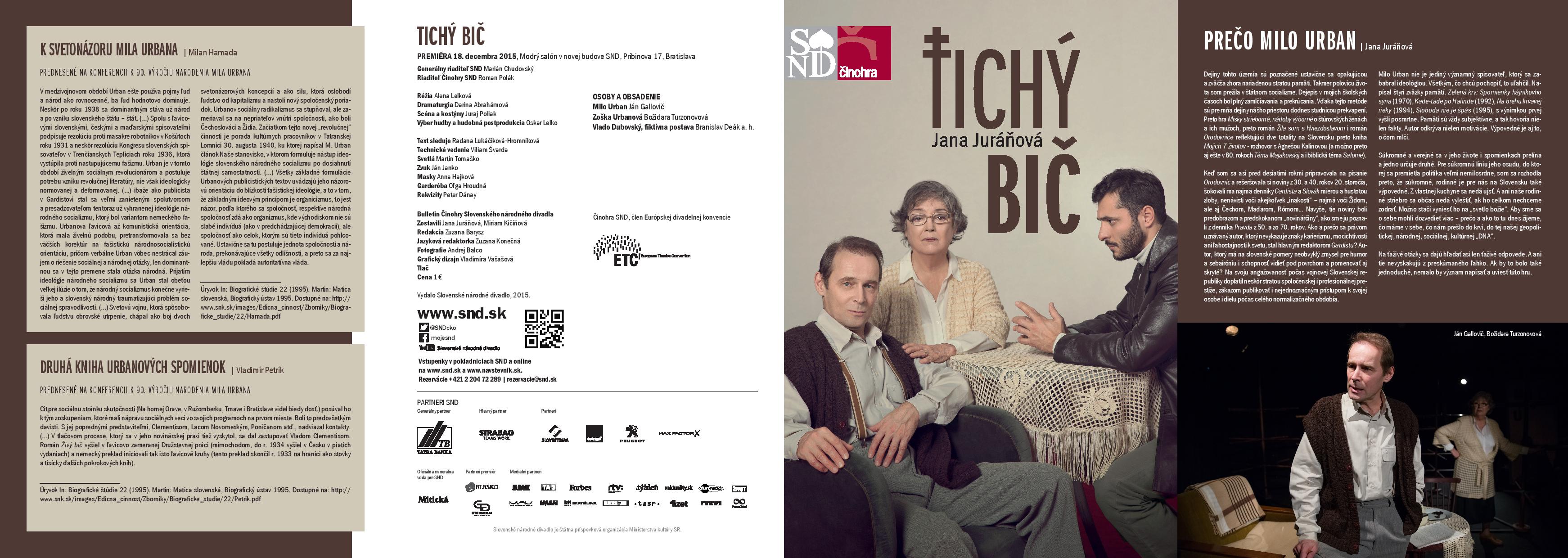

One such figure is the protagonist of The Silent Whip, the acclaimed 20th century Slovak writer Milo Urban. The best of his fiction, written before World War II, particularly the novel The Living Whip, still forms part of our literary canon. Yet he is also one of many Slovak writers who have sullied their reputation by getting entangled with one ideology or another. In the four decades from 1948 until 1989 many authors genuinely believed in the idea of communism, or at least pretended to believe in it in order to be allowed to publish. During the much shorter existence of the wartime Slovak Republic (1939-1945), a satellite of Nazi Germany, quite a few distinguished writers embraced the national socialist ideology. Many of them were condemned after the war and some, for instance Jozef Cíger Hronský, emigrated to South America.

However, Milo Urban’s entanglement with ideology, in his case Nazi ideology, is quite extreme even by Slovak standards: from 1941 to 1945 he served as editor-in-chief of the daily Gardista, the official paper of the Hlinka Guard, a paramilitary organisation controlled by the ruling Hlinka Slovak National Party. In my play I wanted to explore the question of how a writer—by all accounts neither a careerist nor an active Nazi, a distinguished author with keen social awareness and literary talent—could turn into a mouthpiece for fascist ideology.

Some ten years ago, as I studied 1930s and 1940s newspapers while researching one of my novels, I was particularly shocked by the dailies Gardista and Slovák (The Slovak) and the rabid malice and hatred they showed towards any kind of “otherness”—especially Jews but also Czechs, Hungarians, Roma… Furthermore, these papers were the forerunners of the kind of “journalism” practised by the 1950s and 1970s communist daily Pravda.

In my novel Ilona. My Life with the Bard, trans. Julia and Peter Sherwood, 2014) I re-imagined the life of a woman who was made invisible and who despite, or precisely because of, being an invisible, overlooked shadow of her husband embodies the ideal of a wife, and not only in the 19th century. However, in focusing on Ilona, the wife of Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav, Slovakia’s seminal and most acclaimed poet, my intention was not to diminish his significance but rather to take a critical look at the Slovaks’ tendency to glorify their literary bards.

Similarly, in writing The Silent Whip (2015) rather than to detract from Urban’s significance as a writer anchored in the interwar period, I set out to explore how it is possible that, even 70 years after World War II and more than a quarter century since the end of communism, none of the Slovakia’s numerous literary institutions has engaged in a critical examination of this eminent fiction writer and his collaboration with the fascist regime, especially as his is such a clear-cut and well-documented case. I was quite astonished to discover that, apart from the literary critic and historian Milan Hamada, nobody had critically examined Milo Urban’s fiction, journalism and political views. Nor has anyone bothered to put under the spotlight his post-war literary output (four novels), his memoirs (four volumes, three published posthumously after 1989), or his editorial and journalistic work under the wartime Slovak republic.

Yet this was an author who had displayed an unusually highly developed sense of humour and self-irony and demonstrated an ability to see under the surface and articulate what was hidden underneath. His wartime activities cost him his social and professional prestige after the war, his books were banned, and his reception was very ambivalent. The novels he wrote later in life are unreadable, schematic, insincere and of a poor literary quality; his memoirs, written in the same period, include occasional flashes of his erstwhile literary talent, while at the same time sadly proving that if an author uses his memory selectively, refusing to interrogate his own views and writing only to exculpate himself, his work will be reduced to a source of information on his moral failure. For me his memoirs, alongside his articles for the papers Gardista and Slovák, certainly served as the main source of information on his fate and particularly on his moral failure.

The action of my play The Silent Whip takes place in the kitchen of an apartment in a village near the capital Bratislava where an aging Milo Urban is living out his final years with his wife Žoška. The kitchen stands for the pettiness, the false sense of security and their seclusion. The Urbans receive several visits from a young journalist, an admirer of Milo Urban’s writing. However, his own Jewish background compels him to ask awkward questions about Urban’s wartime activities. Milo Urban won’t admit his guilt and points out that he had personally rescued several Jews, although his journalism helped fan the flames of hatred against every minority and prepare the ideological ground for their extermination. It gradually transpires that his greatest supporter at the time and the person who had insisted that he should stick to the well-paid job of editor-in-chief of a Nazi daily was his wife Žoška, a kindly lady who welcomes the young journalist and showers him with motherly attention. This is what she has to say about the war: “Those were the most wonderful and happiest days of our lives. Our third daughter was born in the difficult days at the end of World War II. After the war we had to endure many trials and tribulations. We’ve experienced great hardship.”

As Milo Urban tries to exculpate himself from what had happened to the Jews and other persecuted minorities during the war, I’ve cited authentic passages from his journalism. However, his conflict with the young journalist does not bring about catharsis. Urban remains silent as the journalist recalls what his father had told him: “You see, every Hlinka Guard member had his own Jew but I didn’t want to be the Jew of the editor of Gardista” to explain why his father had not testified on Urban’s behalf, even though the writer had rescued him from a transport at the last minute. (In 1946 and 1948 Urban escaped imprisonment because he indeed helped to save some people.)

My play about Milo Urban was meant to show that Slovakia hasn’t gone through a process of de-Nazification, in the same way that some decades later it didn’t go through de-Communisation. This had terrible ramifications: in 2013 year Marián Kotleba, leader of the ultranationalist People’s Party-Our Slovakia, a fervent admirer of the wartime Slovak government who had, until recently, paraded in a black uniform modelled on the Hlinka Guard, was elected governor of the Banská Bystrica region in Central Slovakia. The play ends with a recording of his party members’ chanting.

The problem with Slovak culture is not just that some of its representatives succumbed to one ideology or another, whether for opportunist reasons or out of naiveté. We have a much graver problem: our society is unwilling and unable to fully and profoundly come to terms with the legacy of either totalitarian regime, for example by critically examining their individual representatives. Honest attempts to do so in literature or the theatre have gone largely unnoticed, ignored by the media that like to present themselves as the shining light of democracy in Slovakia.

Some years ago, when I was translating Virginia Woolf’s book The Three Guineas, I was fascinated to discover that this brilliant writer had also shown incredible political clear-sightedness. She had seen through Nazism and through Hitler’s character, regarding him as the pinnacle of dehumanized patriarchy. This aspect of Virginia Woolf’s work has been unjustly, and I suspect consciously and intentionally, neglected. Translating Judith L. Herman’s Trauma and Recovery the message that stuck in my mind is that if nations and states fail to come to terms with the traumas of their past, the traumas will catch up with them.

In Slovakia they have been catching up with us ever since the first free election after 1989, when the electorate ushered in a dark period under Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar. Earlier this month, following four years of one-party rule that was rather reminiscent of the totalitarian communist period, enlivened only by boundless corruption and the growing power of our oligarchs, we have ushered into our parliament Marián Kotleba and his right- wing extremists, who use fascist symbols in their periodicals, greet each other by shouting Na stráž, the Slovak equivalent of Sieg Heil, and make no bones about their hatred of minorities.

The recording played at the end of The Silent Whip was made at Kotleba’s party meeting after he won the election for governor. Now that his party, which openly indulges its nostalgia for the wartime Slovak Republic, has entered parliament with 14 seats, it may come to be regarded as a legitimate political force.

I don’t think is enough to shout from the rooftops that Kotleba is a Nazi. I believe that we also must take a good look at the Nazis in our past, examine their motivations, their cowardice and their failures. We have to be aware of the skeletons in our cupboard instead of adding to them. We should use them to teach anatomy lessons in our nation’s memory instead of dressing them up in uniforms and turning them into cultural icons.

*****

Jana Juráňová is an acclaimed Slovak writer, playwright, essayist, translator and publisher, co-founder and editor of the feminist educational and publishing project ASPEKT. She lives in Bratislava. She has written several plays for theatre and radio, children’s stories and short stories. Her most recent collection of short stories is Heavenly Loves (2010) and her longer fiction includes the feminist thriller The Suffering of the Old Tomcat, Beadswomen (2006) and Ilona. My Life with the Bard (2008). The latter two novels were shortlisted for Slovakia’s most prestigious literary prize, the Anasoft Litera Award, and a number of Juráňová’s short stories have appeared in German, English, Hungarian, Polish, Czech, and Norwegian translation. In 2012 she published the memoir of the prominent journalist and translator, Agneša Kalinová, My Seven Lives, in the form of a book-length interview. Her latest work of fiction, the novella Unfinished Business appeared in 2013, followed by the play The Silent Whip in 2015. Jana Juráňová’s translations from English include Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas and Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble as well as books by Margaret Atwood and Jeanette Winterson.