Last year, a hashtag became wildly popular in the American literary scene for an author no one has seen and who writes in a foreign language.

This year, a different author—one whom everyone knows because she’s won a Pulitzer Prize, among other honors—is taking the nearly unprecedented step of publishing a memoir called In Other Words in dual language format. And—wait for it—the part of the book that contains her original manuscript isn’t in English.

The two authors have something in common: they both write in Italian. That, and they could be presiding over a renaissance in Italian literature (Well, they may be, if publishers, cultural organizations and/or the Italian government exploit this convergence. More on this later).

The first writer is the mysterious Italian novelist Elena Ferrante, celebrated on Twitter by the slogan #ferrantefever, and the second is Jhumpa Lahiri, a British-born, American citizen who decamped to Rome in 2012, with the unusual project of ceasing to read and write in English. (The two have something else in common: Ann Goldstein is their Italian-English translator).

One author shooting to prominence, and shining a spotlight on Italian literature from the inside, the other already enjoying almost unparalleled prominence in American letters, choosing to embark on a courageous path—one which will almost certain provoke curiosity about Italian among non-Italian readers.

Is Italian literature, both in translation and in original form, having its moment? Oh gosh I hope so.

But, of course, within the world of publishing, it’s not a simple question, and hence no simple answer will suffice. Michael Reynolds, editor-in-chief of Europa Editions, Ferrante’s publisher, hesitates to say Italian literature is having a moment.

“It may once the Ferrante effect has shaken its way through the book industry, which is historically a fairly conservative (small c) industry inasmuch as it favors repetition and emulation over innovation,” he said in an email.

While he said “Italy and Italian literature…still have a strong hold on the imaginations of foreigners,” Reynolds cautioned that large publishers in Italy are “in turmoil.”

That’s good context for the question I’ve raised. Chad Post with Open Letter Books brings good perspective, too, in the form of some chilling stats (they should be chilling to publishers in Italy, a country that collectively has what amounts to a crush on America and the English-speaking world). In a report Post prepared for the Italian government, he found that of the 2,394 works in translation published in the U.S. between 2012 and 2014, only 174 were originally written in Italian. By comparison, there were 539 French books translated, and 385 German works.

“It’s a huge gap,” Post said in an interview.

But as someone who’s fluent in Italian and constantly plowing through one Italian novel or another, I’m thrilled Lahiri is giving voice to the strange, obsessive pull of the Italian language that I, too, have felt ever since I stepped foot in Italy long ago. She’s written a book that outs the spell Italian has cast over me and millions of others, one that’s part and parcel of the mystery one sees in Italy around every turn. Italy is eternally beguiling—and especially so when you speak the language.

In an excerpt of her diary published last year by the Italian literary magazine Nuovi Argomenti, she writes at one point, “Non ho mai provato una felicità più pura di questa.” I’ve never experienced a purer state of happiness than this. I surmise she, too, like me, has discovered there’s something about reading, speaking or hearing Italian that resembles the moment in an aria when the singer is no longer saying words but rather voicing untranslatable emotion. It’s like leaving earth for a few seconds.

In many ways, one could argue a surge of interest in Italian literature—if that’s what occurs—is a long time coming, and for more reasons than one. America has nothing short of a love affair with all things Italian. Italian food, Italian coffee, Italian design. What’s missing is an equally obsessive interest in Italian literature. It is no longer unusual, after all, to find Illy coffee in American supermarkets (and I don’t mean just Dean and Deluca). Add to that the exuberance with which America met the return of Fiat to its car market in 2011, and I think my case is clear that Americans love all things ‘Made in Italy.’ So why not literature?

Ferrante’s success is notable for many reasons. The Italian novelist conquered the English-speaking literary world with a series of four long, dense books set in Naples. Each begins with a thick, forest-like chart of characters with bios and descriptions. The books take place over the course of two women’s lifetimes, taking in Italian political movements and social struggles that may not have been familiar to English-language readers.

Much has been written about the intensity of Ferrante’s following—second only to the intensity Ferrante brings to her descriptions of female longing and the choke-hold responsibility of parenting. But it’s worth noting that Ferrante’s translator, Goldstein, a writer for the New Yorker, has become a household name among literary types from New York to Oxford. To indulge a clichéd question, when was the last time a translator was a household name (even just among households that subscribe to the New Yorker)? Constance Garnett? William Weaver?

And yet, as the Economist noted dryly last year, “Italy produces few international bestsellers.” Ferrante has built on the more modest successes of other Italian writers who have a following in America and the rest of the English-speaking world in recent years, including Paolo Giordano and Alessandro Baricco.

Looking forward, as Post notes, “People may go looking for the next Ferrante but not necessarily in Italian.”

Enter Jhumpa Lahiri.

Intensity is a word you may recall when you begin to read Lahiri’s reflections on her adopted language and homeland. At one point in the excerpt from Nuovi Argomenti she writes, “Carissima Roma, quanto ti voglio bene.” My dearest Rome, I love you so much. (Literally, she’s asking, how much do I love you? The answer might be infinite). Lahiri’s step is so unusual it’s hard to find similar recent examples. You might say, well, look at Nabokov, who made a conscious decision to write exclusively in English after publishing in his native Russian. But in many ways, the example pales. Who goes from writing in one the world’s most dominant languages to writing in Italian, exclusively?

Moreover, her new memoir is published in dual language format. When was the last time a Pulitzer Prize winner published a book in two languages?

Oh I know, I know, literature in translation is never an easy sell in America. And the idea that thousands or millions of Americans would follow Lahiri’s example and learn a foreign language—well, it’s not even an idea.

And yet it is tempting to leap to all kinds of conclusions!

Lahiri is not operating in obscurity. When you consider that her debut short-story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, has sold 15 million copies worldwide, is it so strange to think that a few people will find her choice so compelling that they, too, will take the leap?

People are watching what she does. And what has she done? Like millions of other Americans throughout history, she’s proclaimed that she’s in love with Italy. But she does so with Italian words, Italian words she’s published, no less—and that is different.

The question is, will this love affair with Italian help galvanize Italian publishers, cultural organizations and the Italian government to invest more in bringing literature ‘Made in Italy’ to the English-speaking world? Will Italy begin selling Italian language and cultural supremacy on these shores in the same way France promotes the Alliance Francaise?

Oh gosh, I hope so.

In the wake of Ferrante’s success, one finds many southern Italian female writers penning bold, provocative works (just to pick one strain of Italian fiction). Among them Viola Di Grado whose unusual book Hollow Heart, published by Europa, is narrated by a dead woman. The book, translated by Antony Shugaar, was just selected for the short list for PEN’s annual Translation Prize for book-length translations of prose into English.

Moreover, the year ahead promises to bring us a few more Italian literature. Andrea Molesini’s Not All Bastards Are from Vienna (Grove) is already out and garnering pretty good reviews from, among other outlets, The New York Times, which called it “wonderfully alive.” According to the translation database compiled by Three Percent, which is based at the University of Rochester and overseen by Chad Post, a number of interesting Italian titles will be making it to American shores, including Eva Sleeps by Francesca Melandri (Europa) and Fine Line by Gianrico Carofiglio (Bitter Lemon). I say cin-cin to the momentum continuing. Forza Italia!

*

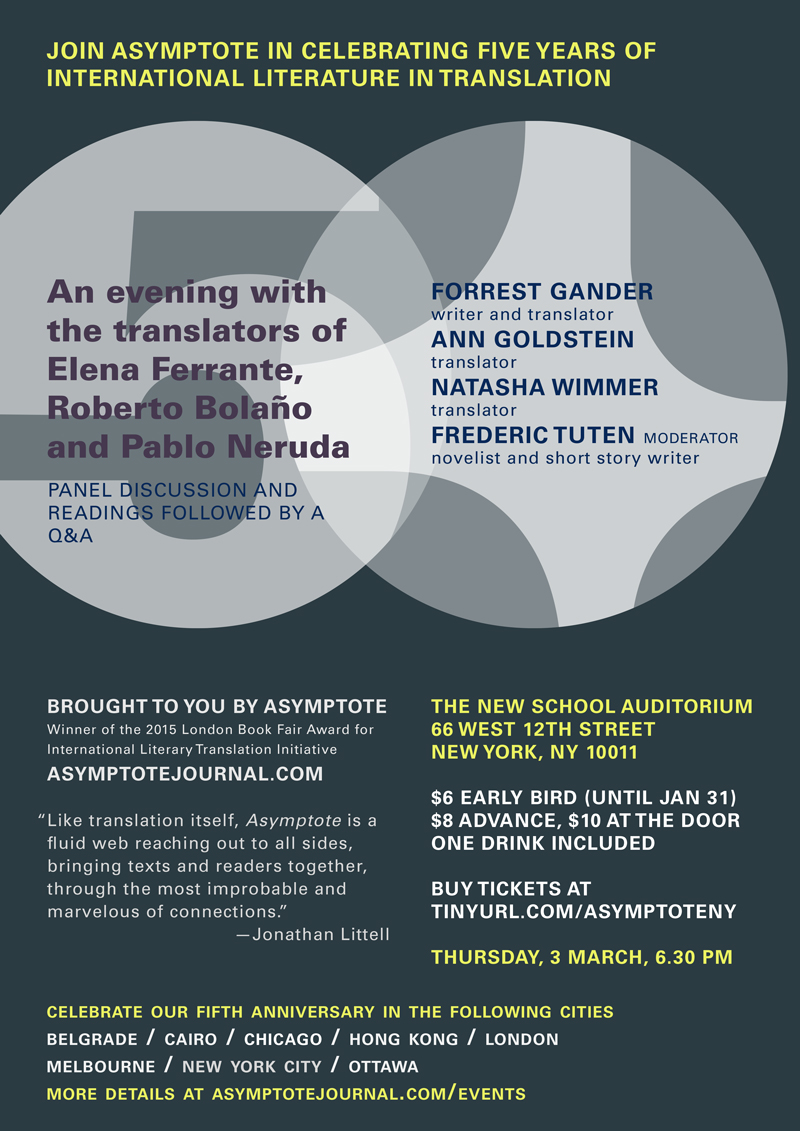

New Yorkers: Please join us for our anniversary event coming up on Mar 3 (Thursday), featuring Ann Goldstein, Natasha Wimmer and Forrest Gander, who will give readings and then join a discussion about world literature moderated by Frederic Tuten. Tickets can already be bought here, and you can RSVP to our event or invite your friends to it via our Facebook Event page here. (If you use the discount code CELEBRATEWORLDLIT, you can still get $6 tickets, one drink included, while stocks last. So, don’t wait; hurry!)