January 11, 2016. To some, David Bowie’s death may not seem more than the news of the moment.

Its presence everywhere in the media as I write this today proves nothing. Anyone can go viral on our networks if they manage to go beyond the threshold of public perception: if they become attractive or loathsome enough. Nothing else is needed to get the attention of millions of bored people in a country (or more than one). This happens when a celebrity dies, too. Almost every day one does, somewhere, and the death needs to compete against any other infotainment that comes our way.

A few days before Bowie, it was Pierre Boulez—the great composer and conductor whose influence on classical music could be comparable to that of Bowie on its own milieu—and no one cared, aside from a few connoisseurs of classical music. Here in Mexico, the release of Blackstar, Bowie’s last album, was forced to compete for the local audience’s attention with the news surrounding the capture of drug kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán and the secret interview that actor Sean Penn did with him. (That piece was published last weekend on the Rolling Stone website.)

Nor is there proof in either the tone or the abundance of the obituaries published online, whether they range from mere admiration to an almost religious fervor. Our time suggests greatness can be found—or created—literally anywhere, because it depends on the subjective perception of the observer, which can be influenced beyond their control in many ways. If this is true, it could also be said that anything can become an object of adoration: anything can soothe the feelings of frustration and insignificance that move us to look beyond ourselves for a justification of our own existence. Perhaps, then, Bowie is not all that important: maybe his gifts and his accomplishments are exaggerated by those of us who look at them with affection and have made them “a part of our own lives”; others have done the same with One Direction, after all, or with Justin Bieber…

Novelist Martin Amis thought so in 1973: in a piece for New Statesman magazine, Amis denied Bowie’s endurance as an artist and wrote, “Mr Bowie was just a mild fad hystericised by ‘the media,’ an entrepreneur of camp who knew how little, as well as how much, he could get away with.” Those words could have been written today by a Facebook cynic, complaining about posts with Bowie memes or YouTube videos of his songs and performances.

Amis was wrong when he thought Bowie would not survive the early seventies, but someone who did not love his oeuvre (or have any knowledge of it) could look at today’s expressions of grief, compare them to the relative silence that no doubt will replace them tomorrow and conclude that Bowie will be forgotten just a few decades later than predicted.

Of course, I don’t believe so. But Bowie’s death not only has happened in an age of the banal and the momentary. His life—or the life he invited us to imagine through his works—leaves a trace that will be difficult to appreciate because it’s invisible by now. So many have assimilated him, so many have tried to imitate him that we mostly have stopped perceiving him. His transgressions are our mores. And his influence is not limited to a musical genre, rock, among whose greatest figures only Bowie himself remained as an artist who, well past youth, was still looking for ways to be at least innovative: to pursue something other than the memory of past glories.

* * *

January 12. Also, that which happens to other artists of enormous influence also happened to Bowie: he has been copied, above all, superficially. Those accomplishments so rare as to be impossible to repeat have been made to seem easy. Here’s just one example.

For decades, I’ve been coming across the same cliché: David Bowie’s “chameleon-like abilities” (look for the words “capacidad camaleónica,” in Spanish). Reporters and reviewers wrote these words every time a new album came out or whenever there was anything in the news about him. Of course, the term refers to his changing image, to the many characters he invented as protagonists or spokespeople for his different musical projects.

Each character had his own songs and was usually (though not always) represented by Bowie himself, who changed his clothing, hairdo, and makeup for live performances. The most famous ones are those of his early years of stardom: Major Tom, the Thin White Duke and, most of all, Ziggy Stardust. But Bowie kept creating characters until the very end. Some, like Nathan Adler or Screamin’ Lord Byron, are clearly his creations and can be seen at the center of projects made after the seventies; others, like Jareth the Goblin King (from Jim Henson’s 1986 movie, Labyrinth), were invented by other artists but inhabited by Bowie with an ease made possible precisely by his great imagination and performing talents; and the most recent ones are only a few days old.

(Bowie’s last singles, “Blackstar” and “Lazarus,” were released along with music videos directed by video artist Johan Renck, who has confirmed that Bowie performed three different roles in them, the most iconic of which has to be the one they called Button Eyes: the old man, dying on a bed, blindfolded with two fake eyes on the blindfold, and who is emblematic of the thoughts about death that listeners and commentators all over the world have begun to find in Blackstar.)

Today it is common to see a media uproar about any famous artist who changes their clothes or hairdo, but virtually none of those “changes” are truly as profound as Bowie’s transformations actually were: changing his music along with his appearance, jettisoning previously used styles, and using the new stage persona to create a representation of a mood or a human character, with a context and a capacity to suggest influences, intertextual references, a particular relationship with its surroundings. Bowie did this many times, and with success more than once, especially during the first decades of his career. Among the many changes in popular culture he championed are glam rock, several techniques of musical experimentation, the contemporary notion of the rockstar—and, perhaps most important of all, the militant and ironic critique of numerous gender stereotypes, manifested most visibly in some of his early characters’ androgyny.

A stray observation: in the recent present, Bowie’s insights about show business in the Internet age were no less than prophetic: in 2002, he stated that “Music itself [was] going to become like running water or electricity,” suggesting the future dominance of digital services for the dissemination of recorded music. Now, as I write, I’m listening to Hunky Dory on Spotify (and I observe that the most popular song by Paul McCartney is actually a 2015 single in which he is featured alongside Rihanna and Kanye West).

And today, yes, comments about Bowie are less frequent than yesterday, though the posts haven’t faded away as fast as those about other celebrities.

Probably the artist who followed closest in Bowie’s footsteps is a relatively obscure one: the German-born singer Klaus Nomi, who in 1979 did backup vocals for Bowie on Saturday Night Live. Nomi was inspired by a plastic suit worn by Bowie—created by him and designer Mark Ravitz, based on early 20th century avant-garde designs— to create a suit of his own, which he wore for the rest his career, cut short by his death in 1983 but during which he fused influences from opera, cabaret and the nascent New York gay scene. Few went as far as Nomi in approaching Bowie’s iconic character when the notion of creating an iconic image still made sense: Michael Jackson as a zombie in the music video “Thriller,” Marilyn Manson in his more literal Bowie imitation for his Mechanical Animals album…

* * *

January 13. I was born in 1970, so I didn’t have the chance to really know David Bowie’s early work as it was being created: those albums and performances that in the last few days have been described as the most influential, the ones in which Bowie best perceived —or most potently affected— the trends of English-speaking culture and beyond. His 1980s pop phase, which coincided with my early teens, meant nothing to me because it seemed just more of the same garish, soothing MTV filler that was on TV everywhere. The “Blue Jean” music video was broadcast after Billy Idol’s “Eyes Without a Face” and before Cyndi Lauper’s “She Bop”. I had seen Bowie’s face at the movies, both in Labyrinth and on Tony Scott’s The Hunger (1983), but as good as those performances may have been (and they were), they could not have elevated what Bowie’s music seemed to be at the time.

My own discovery came later, through one of the least successful and beloved Bowie projects (at least to diehard fans): the first album by the band Tin Machine (1989), a group in which Bowie was “just the singer” and was made up of the brothers Hunt and Tony Sales on drums and bass and Reeves Gabrels on guitar. The change—according to the the critics of the day—had to be a reaction against the pop weakening of Bowie as a soloist during the previous years and an attempt to be relevant again. Later on, there was heavy criticism (at least in English-speaking countries) against the perceived superficiality of the lyrics, and—typical of the showbiz press—against the fact that the band was not as commercially successful as expected, as if this were a cause and not an effect. The truth is that Bowie’s stature, even as a frontman, was much too big for a band of peers, and the Tin Machine II album (1989) was noticeably inferior to its predecessor, despite some pure and explosive rock moments.

But the first Tin Machine’s music was a tremendous and welcome blow for me and some close friends at the time: Bowie’s lyrics, though oblique, were clearly addressing the anguish of those years when the Cold War had not yet ended and the Berlin Wall was yet to fall, and as we were just beginning to glimpse the menaces of the 21st century (“Money goes to money heaven / Bodies go to body hell”, sings Bowie on “I Can’t Read”, the album’s best song, managing also to turn John Lennon’s “Working Class Hero” into a cry of pure rage). Anchored by Gabrels’ savage and inventive guitars, the album was also an obscene gesture to the insipidness of pop music to which we felt condemned. It was a rough, difficult album to listen to, and we loved it for that. (Bowie kept Gabrels close after Tin Machine disbanded, and much of his best 90s output, from Outside to “… hours” features Gabrels’ contributions.)

After that experience came all the others: until today, on and off (though not that much) I’ve been exploring all of David Bowie’s music. I’m listening to it right now. A Facebook cynic wrote today that “nothing has changed” after Bowie’s death, and I’m reminded that that’s the title of an anthology of David Bowie hits.

I know Bowie’s oeuvre is forever closed by its creator’s death (the posthumous discoveries, as numerous as they will no doubt be, don’t count). But I also know that, even when I have listened to all of it, I will be returning to many songs and albums with affection but, most of all, with admiration. If there’s any justice, the works of David Bowie will never cease to amaze us as they do now: they will not cease to make us aware of their extraordinary breadth and brilliance.

***

Translated from the Spanish by the author and George Henson.

***

Alberto Chimal (1970) is the author of the novels La torre y el jardín(2012) and Los esclavos (2009), as well as numerous short-story collections, which include Los atacantes (2015), Gente del mundo(2014), Manda Fuego (2013), El último explorador (2012), La ciudad imaginada (2009), and Éstos son los días (2004), in addition to books of essays and a handbook of creative writing. Alberto holds a Master’s degree in Comparative Literature from the National Autonomous University in Mexico City, where he teaches workshops in creative writing and is a member of the faculty of the Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana. A leading practitioner and researcher on the “fantastic” and online writing, he has presented numerous virtual projects, including Día Común, #MuchosPasados and #CiudadX, at international festivals such as #TwitterFiction (USA) and Ciudad Mínima (Ecuador). His website can be found here.

George Henson is a translator of contemporary Latin American and Spanish prose. He has translated works by many notable writers, including Elena Poniatowska, Andrés Neuman, Claudia Salazar, Raquel Castro, Leonardo Padura, and Luis Jorge Boone. His translations have appeared variously in Words Without Borders,Buenos Aires Review, BOMB, Literal, and The Literary Review. His translations of Alberto Chimal have appeared in The Kenyon Review,Flash Fiction International, and World Literature Today. His book-length translations include Sergio Pitol’s The Art of Flight and The Journey, both with Deep Vellum Publishing. George is a member of the Spanish faculty at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where he is affiliated with the Center for Translation Studies. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Dallas.

***

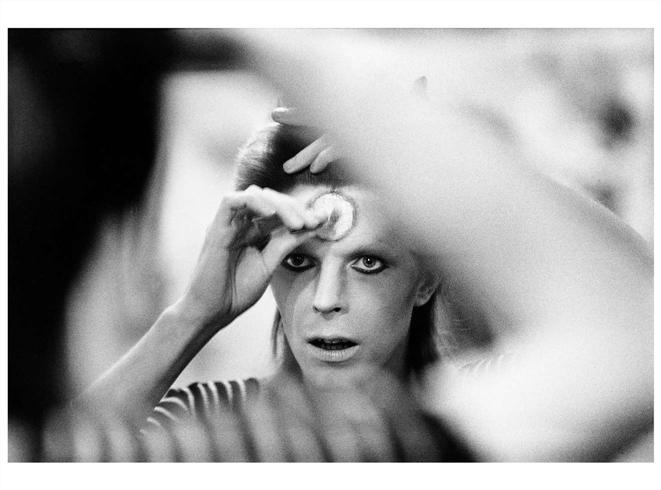

Image: Mick Rock, from Morrison Hotel Photography.