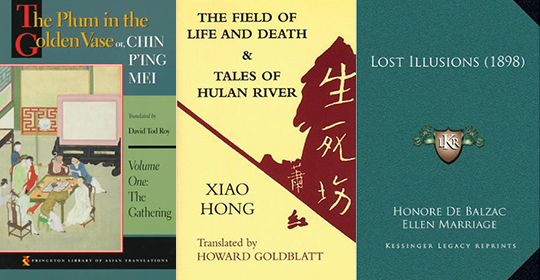

When I think about the best books I read this year, I inevitably think about when and where I read them. Starting in late December of last year, I spent many nights hunched over my desk, reading The Plum in the Golden Vase, the late 16th century Chinese masterpiece about the lecherous, murderous, thoroughly corrupt local magnate Ximen Qing and his six equally infamous wives, alongside David Tod Roy’s now complete five-volume translation (Princeton University Press, 1993-2013). When I finished reading both, it had become a warm Boston spring. The giant Chinese novels of the late Ming and early Qing periods (from the 16th to the late 18th century) are long for a reason: when you spend months in the world of the novel, that world becomes a significant part of your own life, heightening the sensation of microcosm. In the case of The Plum in the Golden Vase, this immersion imperils the soul. The novel reads like a thousands-page long sneer—it depicts a world in which everyone and everything, great and small, is morally compromised, and it seems to delight in its own bleak view of the world. Consequently, it’s a novel that is easy to admire and hard to love. The translation, too, wears on the reader by the end. It is complete and readable, but the occasional awkward, overly literal interpretations that are tolerable in the first volume become irritating by the fifth. “Short-life,” for example, Roy’s literal translation of the late Ming curse duanming, loses its amusing novelty by the thousandth repetition. Yet Roy’s translation is a masterwork for other reasons. Each volume comes with about a hundred-odd pages of footnotes tracing the origin of each and every oblique reference and piece of quoted poetry and prose in the novel. Roy’s scholarly tenacity borders on obsession: in order to get the jargon of Ming-era dominoes just right, Roy consults no less than four extant domino manuals from the Ming and Qing. Working through a massive scholarly apparatus that took over twenty years to construct puts the scant four or five months it takes to read the translation in perspective. There’s careful reading, and then there’s careful reading.

I read the lively Ellen Marriage translation of Balzac’s Lost Illusions this year on a bullet train racing across Japan, perhaps the only setting that could match the breakneck pace of Balzac’s tale of the tragic friendship between a social-climbing poet and an increasingly impoverished printer. I find the legend about Balzac composing his novels by downing an entire pot of coffee and writing all through the night exceptionally easy to believe. One doesn’t read a Balzac novel so much as one mainlines it. Consider, for example, this description of the cynical social operator M. du Châtelet:

Supple, envious, never at a loss, there was nothing that he did not know—nothing that he really knew. He knew nothing, for instance, of music, but he could sit down to the piano and accompany, after a fashion, a woman who consented after much pressing to sing a ballad learned by heart in a month of hard practice. Incapable though he was of any feeling for poetry, he would boldly ask permission to retire for ten minutes to compose an impromptu, and return with a quatrain, flat as a pancake, wherein rhyme did duty for reason.

The book averages about one devastating witticism per line for the several hundred pages of its length. It is hard to imagine anyone else having the brazen confidence in their own pen to narrate so much without worrying about irritating the reader; Balzac, to use Cheryl Strayed’s maxim, truly does write like a motherfucker. And, despite being virulently right-wing, Balzac used his pen to puncture not only radical chic, but also insipid aristocratic pretension. Such fairness and balance, in this era of Trump, seems a downright utopian vision: the hope that, though we will not all agree on politics, we will at least agree not to let politics turn us into fools.

I stayed in all of Halloween weekend to read Xiao Hong’s short novel Field of Life and Death (I read it in the original, but there is a translation by Howard Goldblatt available), and it turned out to be a suitably grim experience. In this look at the lives of peasants in 1930s Manchuria, Xiao Hong insists on a brutal documentary realism: warm entrails hang on the fence of a horse slaughterhouse; a man enraged by his poverty dashes his own child’s brains out; the spectacle of women screaming from the pain of childbirth is framed by the image of bitches and sows giving birth. Though the novel was quickly appropriated to serve a nationalist narrative of resistance against the Japanese, Xiao Hong herself is quite clear that the misery she describes, rooted in a society that treats people and especially women scarcely better than livestock, preexists the Japanese occupation, which only serves to make that misery unbearable. As one character succinctly puts it, “I used to hate men, and now I also hate the Japanese.” Sadly, Xiao Hong never had the chance to further develop her unique feminist vision of Chinese society. She died at the age of thirty in 1942 in Hong Kong, having traveled thousands of miles from her home in Heilongjiang, leaving behind two husbands and a deathbed lover. Let her short but full life be an example to us readers: make hay (and read books) while the sun shines!

Dylan Suher is a contributing editor at Asymptote. He was born and raised in Brooklyn. He has published reviews, criticism, and essays in The Millions, the Review of Contemporary Fiction, and The New York Times. He is currently a graduate student in modern Chinese literature at Harvard University.