“Clarice inspires big feelings. As with the ‘rare thing herself’ from ‘The Smallest Woman in the World,’ those who love her want her for their very own. But no one can claim the key to her entirely, not even in Portuguese. She haunts us each in different ways. I have presented you the Clarice that I hear best.”

By spending the last two years translating nearly four decades of Clarice Lispector’s work in what she calls “a one-woman vaudeville act,” Katrina Dodson has joined a club of translators (trumpeted by Lispector’s biographer and de facto proselytizer, Benjamin Moser), whose interpretations of the Brazilian writer have now generated a skyscraping tidal wave. Though recognized by Brazilians as their greatest modern writer, Lispector was little-known among English-speaking readers until the beginning of this decade. Today, she is the first Brazilian writer to appear on the cover of the New York Times’ Sunday Book Review (July 2015). For the first time in English, Complete Stories brings together all the short stories that established her legacy in Portuguese.

Lispector gives the impression of a woman looking from the outside in, always taking notes. Like Borges, she expects you to follow her fantastic trains of thought, but she is unconcerned as to whether you enjoy the ride or not. In Complete Stories, eggs become infinite metaphoric permutations (interestingly, Lispector would die of ovarian cancer, on the eve of her 57th birthday), a lonely, red-headed girl and a red-headed basset hound discover they are soulmates, but destined never to be together, and a woman has a face.

Because in Lispector’s world—and Dodson’s translation—it must be asserted that a woman has a face, as if such a characteristic is not naturally of this world. These familiar details, made new —especially during fevered sequences when geography reflects a character’s unraveling—are what end up grinding our faces into the pavement as Lispector gazes on, coolly, but not unkindly, with great curiosity from above.

***

MB: When did you first encounter Clarice Lispector, and did you have a form of epiphany moment when you discovered her?

KD: I first started reading her in 2003. I was living in Rio de Janeiro and teaching English at a private English school called Britannia, and I had moved to Brazil that year speaking some Portuguese but, but it was—I spoke French, and then I was listening to these cassette tapes. That’s how long ago it was [laughs]. I would listen to cassette tapes that they would use to teach the Foreign Service how to learn a foreign language. I would listen to these Portuguese tapes before going.

So I was learning Portuguese, but I wanted to read something serious. I was reading comic books and children’s books, and then I thought, okay, I want to know who the Brazilian female authors are, and everyone mentioned Clarice Lispector. I had been in Brazil for almost a year, and it was right before the winter break, where you get the end of December through January off. I went into this bookstore and I found her, and I just chose The Passion According to G.H. because I liked the title [laughs]. It just sounds like, oh, the passion. What’s the G.H.? Sounds good.

I picked it off the bookshelf. I took it with me to the Amazon. I did this crazy trip to the Amazon where it was like six days on a kayak, down this tributary of the Rio Negro, and then after that, I read The Passion According to G.H. on the ferryboat you take from Manaus to Belém. It’s deep in the forest, in the jungle, basically out to the coast. Three days on this boat where you string up your hammock and it’s just all these local people. You’re making all these stops in villages, and people are coming on and off, and I’m reading what I think is her most difficult and intense book. It’s this woman wandering around her apartment having this deep, spiritual, mystical experience. She takes a bite out of a cockroach and kind of goes back to primordial times, and I’m here in this land of enormous insects, totally disoriented. I just didn’t understand a thing. I was reading the words, like “What is this? This is so crazy. Am I just losing my mind or is it just that I don’t really speak Portuguese well enough?” It was a very intense experience. I didn’t know what to think of it.

It was only after I came back to Rio, and then I started classes at PUC (Pontifícia Universidade Católica), the Catholic university there. I started taking literature classes there and I re-encountered her through the literature classes. It made it easier to read, but I realized this is just a really, really crazy writer. I really liked it, but it just took me so long just to feel like I could understand what she was doing. I still think I [don’t] entirely understand it, and that’s what makes her so compelling. I don’t think she wants to be completely understood, and she wouldn’t have understood herself. I think it’s in “The Egg and the Chicken,” one of her most difficult stories—I think it’s there she says “Understanding is the proof of error.”

I think people have a strong emotional and spiritual response to her. She does offer a lot intellectually. You can analyze her stories to the end of time, but I think the way to into her is to let go of that need to understand her in a rational way. Over time, my relationship to her has changed. But I’m very glad I read her for the first time just on my own, and not in a class. I felt like I could just kind of dive into her. I didn’t know a lot about her and I was on vacation so I was just inside the world, but I didn’t feel all this pressure to have to explain her in a class or in a paper to other people. That came later, because then I went to grad school and then I was writing about her, so it was a very different experience.

MB: That brings me to my next question actually. I’ve read an interview with the French feminist writer Hélène Cixous. She was greatly influenced by Clarice in terms of the voice in her fictional writing. She says in an interview [at Trinity College, Cambridge University]:

“I began to read her in 1977, and I only really began to know her text, to be able to respond to it, two years later. Let us say that I worked for two years to really understand her thought. That is the person who encountered Clarice Lispector, which is to say, someone who had a long literary, poetic and political experience, and I had the good fortune to recognize in Clarice Lispector a companion and a contemporary woman.”

Like Hélène Cixous, did you have to put some space between yourself and Clarice at any point, perhaps by conducting some preliminary desk research, like she did, before she began to embark on her as a subject? Or did you have to put space between yourself and Clarice before professionally pursuing her work, or during the process of it?

KD: Well, I think the translation really changed my relationship to her and gave me a much closer relationship, and I’m so grateful for it, because I think, in graduate school, writing about her as an academic, I always felt like it was a failure.

My last chapter of my dissertation was supposed to be about her and I have a draft of it I just ended up dropping. I dropped her entirely from my dissertation. My dissertation’s just about Elizabeth Bishop in Brazil. And part of that’s just because this book completely derailed my dissertation for two years.

When I finished translating, I felt such urgency to finish the dissertation. I just did it in a hurry. But I think having to explain her in a more logic-oriented context, which is academic writing, really distanced me from her work. I always struggled to try to break down her complexity. And I always felt like I fell short in writing about her, in trying to create logical interpretations of her stories or her writing, I always felt like I was falling short, a little bit.

When I got to translate her, it was a relief, because I didn’t have to explain her. It was a much more oblique approach to interpreting her, instead of trying to explain her, I could use my sense of understanding what she was doing or the mood she was creating, and simply try to reproduce that in English.

I think translating is still very interpretive. Words can fall in a number of different ways and you have to choose how you hear it or how it’s going to fall in English. I think I was using a lot of the same techniques of trying to understand her, but because I didn’t have to put it in the form of an argument, but could just do it, it let me rely on a mix of intellect and intuition.

MB: In your translator’s notes, at the end of Complete Stories—bringing up the short story “Love,” which is from the collection Family Ties—you cite it as an example of the translation process particular to Clarice’s language. Could you elaborate on that for our readers?

KD: You mean, the part where I talk about the woman with the face?

MB: Exactly.

KD: The lady with the face. I gave that example because it’s a moment where the story’s just going along and up until that moment, there’s nothing that is extremely strange. That’s the hard part about translating Clarice. She’s not being radically experimental, or she’s not being experimental in a really flamboyant way. It’s always very subtle. She’ll make these subtle distortions, like she’ll change a word ending, or she’ll put a comma where it doesn’t seem like there should be one.

This is one of those moments where there are these suddenly very small deviations that you might not notice as a reader but you definitely notice as a translator, because you’re combing through, word-for-word. It’s very odd, this sentence, “Next to her was a lady in blue, comma, with a face.” Why is that comma there? “And she averted her gaze, comma, quickly.” Normally, it just says, “She averted her gaze quickly.” And the “with a face,” there’s the question of why? What does it mean to point out that someone has a face? As if that were a remarkable fact.

It’s actually a very startling and disturbing moment, and the previous translator completely erases that. It doesn’t make sense, so he took out all the commas. I mean, I put a little bit of it. I don’t think it’s always fair to just nitpick on another person’s translation or just pick out one sentence, because sometimes you don’t have the whole context, but in this sense, I did want to show how the previous translations have really smoothed over her language. There are these moments where you might want to try to explain away the strangeness with an explanation like “Oh, there’s nothing shocking here. This woman is making maybe an expression of disapproval.” It took me a long time to see this. I think there are always these effects of her choices, and you might not see them until the thirtieth time you read the story.

But I realized this is precisely a moment in the story when Ana is having a breakdown. This happens over and over and over again in Clarice, where a character is having a crisis, an internal crisis, and it affects the physical world around them—their perception of the physical world. So, all of a sudden, things that should be banal, like a person’s face—the fact that a person has a face—becomes extremely disorienting. In these moments, I think it’s important to keep those strange commas.

At the end of “The Smallest Woman in the World,” there’s a colon, a very strange and (I think) important colon the previous translator removed and turned to a period. But this colon connects the explorer Marcel Pretre to an old woman at the end who just closes the newspaper where she sees a picture of Little Flower, this picture of a tiny African woman that’s disturbing everyone. She shuts the newspaper and says, “Well, God knows what he’s doing.’ You can go back and read the story after, but it’s this moment where Marcel Pretre’s taking notes and Little Flower’s just been laughing with her pregnant belly. He’s completely thrown off, and he doesn’t know what to do with himself, so he takes notes, and it says something like, “those who didn’t know what to do with themselves took notes.” Actually, I want to find it for you…

[reading] “Marcel Pretre had several difficult moments with himself, but at least he kept busy by taking lots of notes. Those who didn’t take notes had to deal with themselves as best they could.” Colon. And it’s this weird colon because you almost wouldn’t notice it if you were just reading quickly. But that colon sets up an analogy. What do you mean, “those who didn’t take notes had to deal with themselves”? Then you cut to this old woman, shutting the newspaper decisively. Because, look, all I’ll say is this—another colon—“God knows what he’s doing.” You lose that in the first story.

I had a friend who also speaks Portuguese read this story and she also said, why is the colon there? She read the Pontiero version and she knew that he changed it to a period. She said, ‘I don’t know why there’s a colon there. It doesn’t make any sense. If the old woman is one of those who had to deal with themselves, it makes sense, but I would just put a period. And I thought, oh my god. You just explained the end of the story to me. It feels like a non-sequitur, but if you think of it with that colon, all of a sudden, it becomes a story about how different people deal with the unfamiliar or the strange. In the beginning of the story, it’s all about nature, like, what is nature doing? Creating this great variety of people. And the whole story is about just how people don’t know how to deal with this woman they’ve never encountered before. The explorer’s way of dealing with her is to explain her; he gives her a name.

So you have science, you have journalism, and then you have religion at the end, as different ways of explaining or dealing with the unknown. I think I’d gotten that before but having that colon is just this incredible moment where she pulls it all together in a single choice of punctuation. It’s these little moments like that where sometimes you don’t really know what the effect of what she’s doing is going to be.

But you have to trust that there’s a reason she chose something, even if she chose it by intuition. Her work is so coherent to her in that way, that for me and for Ben and all the translators in this new series, I think that is a real goal, to restore these idiosyncrasies in her writing, and it makes her writing so much more powerful than it was previously in English. I do think that’s why people are responding to her. That’s part of the reason people are having such a strong response to her now, with this most recent series of translations.

MB: On the note of “The Smallest Woman in the World,” and female bodies and bodies in Lispector, as a translator, how important is it to have gender-based concerns when translating her descriptions of bodies and particularly female bodies?

KD: I think there’s probably a man out there who could’ve translated these, but I will say I was very happy to have a woman translate, to be the woman to translate. But also I did feel like a woman could bring out a lot of the gender dynamics in these stories, because I do think there’s so much more about women’s experience in the world of men, of female roles, but also, like you said, there’s so much in these stories that connects to what it’s like to experience the world in a woman’s body in a way that I think is much more overt in the stories than in the novels. I’m glad you picked up on that, because each translator is going to come with a different set of affinities. I think that a major way to enter into Clarice Lispector is through women’s experience.

I’m not a mother and I’m not a wife. But there was so much of this that I felt like I was drawing on the experience of watching my mother. My mother had four children. Watching her as a wife and a mother, and just as a woman, you are more attuned to these roles and these other women around you, so I felt like I was channeling a lot of women’s experience that came from my own experience but also just from what I’ve absorbed growing up as a woman. I think that’s the same in Clarice because when she is young, in her first stories she is already writing about older women. She is writing about married women and troubled marriages even before she got married.

In Family Ties and The Foreign Legion, I think that’s where you feel the strongest, when she’s a wife and a mother. Those were during the years when she was married to Maury Gurgel, a Brazilian diplomat and then they divorced. But throughout, she’s got all different kinds of women in different periods of their lives. Throughout the stories. It felt very… I’m not sure what to say about that. I felt like I had a lot of intuition about how to do these women’s voices, or even to describe certain dynamics.

MB: Clarice died on December 9th, 1977. And she was at the age of fifty-six, but on the eve of her fifty-seventh birthday. I feel like she couldn’t have written it herself.

KD: I was just going to say, the other eerie thing about her death is that she died of ovarian cancer. And throughout all her work, eggs have…

MB: “The Chicken.”

KD: Chickens and eggs, right? And eggs take on a lot of symbolic and mystical weight. There are all these strange facts surrounding her. You might have to check with Ben on this, or check in his biography, but I want to say when she gave that television interview to Júlio Lerner—have you watched that?

MB: I haven’t, no.

KD: You should watch it. It’s really brutal to watch. Just to get a sense of her also. She gave that interview with him just a few months before her death and at the end of it she talks about being ready for death, but at the time she didn’t know she had cancer. She wasn’t diagnosed yet. She must have been in pain. But you get this sense in her later work in the 1970s, in Where Were You at Night and The Via Crucis of the Body, of fatigue in her, that she’s just kind of exhausted by writing, by life. But she still has to do it. It’s a very different style of writing than her earlier stories, which I think have more of this feeling of excitement about language, about writing and making stories.

MB: It’s almost infused with… the word I come up with first is “girlishness.” Girlhood, being a young woman…

KD: It’s definitely, yeah. And some of the later ones, too. There are a lot of stories about young girls with almost too much energy. They don’t know what to do with themselves because they feel like they’re special or they have a very romantic relationship to the world around them.

MB: Circling back to eggs and chickens, but on a different level: to my mind, one of Clarice Lispector’s greatest talents is her telescopic philosophications, particularly her focus on animals. She expresses a kind of uncanny kinship with them. I learned from Benjamin Moser’s biography that she had been christened as “Chaya,” which is the Hebrew word for life and also for animal. And in Via Crucis, she wrote, “Any cat, any dog is worth more than literature.”

I would actually say my favorite excerpt from this collection is “Excerpt.” It’s almost like a fever dream sequence, and she focuses in on a fly:

[reading] “Back when Nenê was about to be born and she was in the hospital, lying down, white and scared to death, she doggedly accompanied the buzzing of a fly around a teacup and came to think, in a general, about the tumultuous life of flies. In fact, she concluded there were great studies to be done on these tiny beings. For instance, why is it that, with their beautiful wings, don’t fly higher. Could it be that those wings are powerless, or did flies lack ideals? Another question: what is the mental attitude of flies toward us and toward the teacup, that big lake, sweetened and warm? Indeed, those problems were not worthy of attention. We’re not the ones worthy of them.”

My question is: How do you believe this obsession leads to her larger ruminations? On the relationship between animals and humans, and the relationship between animals and herself as an individual in the world?

KD: I think there’s so much in her writing that is trying to get to the heart of things that are beyond language. I think that writing about animals is one way that she does that, because she captures the physical characteristics of animals so accurately, the way a monkey moves or the way an animal moves or a buffalo. What is that little adorable creature? The coati! The way that a coati tilts its head quizzically.

In “The Buffalo,” and with all those animals, it’s incredible how lifelike she makes them feel. There’s an incredible physical accuracy to how she captures animals. But she also uses them in a way that thinks about communication between human and non-human animals. Just the different ways of being in the world and understanding the world. I think she uses animals in her work to enter into this understanding of existence that is beyond human explanation, but at the same time she has these animals that are just animals. But a lot of time, also, she does play with how much personality animals can have, and how much human see ourselves in animals and relate to each other through animals. We’re relating to our own lives through animals, so I think all of that’s there.

Even in this passage you’ve read, I think there’s a sense in her—and I think you get this in other writers, too—that animals are superior to humans. They have a more unmediated connection to the world. I think that’s the fantasy, or the ideal, of a lot of philosophers and writer. Rilke was one of them too. But there’s this idea that animals have this pure, deeper connection to the heart of the world or the universe because they’re not distracted by language and self-consciousness. I think that current runs through Clarice Lispector. She was so intelligent, so good with words, but I think, especially toward the end of her life, she was struggling with how to write in a way that was a little bit distracted, to write in words without being really limited by words and by thoughts, and to try to have a more intuitive relationship to writing.

MB: If it’s okay, I wanted to dive into the proliferation of Clarice Lispector’s erotic capital. She was certainly a beautiful woman in real life, but as she’s been gaining popularity among English-speaking audiences, at least, it seems her beauty is almost simultaneously attached to her work. For example, my copy of Clarice Lispector, the front and the back, feature two pictures of a very beautiful woman. Elsewhere, I’ve seen images reproduced of her similarly. The one exception I’ve come across is that illustration for the Sunday Book Review, by Jean-Phillipe Delhomme…How do you negotiate the success of her reception with this trend among publishers?

KD: I have mixed feelings about it. Did you see the review that Miranda France wrote in the TLS? And did you see I wrote a letter to the editor about it that came out?

The funny thing about that review was that she was one of a few reviewers that did object to the emphasis placed on Clarice Lispector’s looks and her glamour. Like I said, I have mixed feelings because I do think it’s something that happens much more often to female writers, or only to female writers. I mean, there are certain glamorous men. People talk about Camus or Sartre— no, no, Sartre was not good-looking.

MB: Yeah, definitely just Camus. [laughs]

KD: Or Karl Ove Knausgård. The man looks like a rockstar. He’s such a heartthrob, and people flock. I went to see him at City Arts and Lectures in San Francisco and it was sold out, you know, balcony seats. People were going nuts. And they put his face on the books, too. On one hand I feel like it’s a shame that a writer’s mystique overshadows the actual work. In Brazil, I didn’t know what she looked like when I first read her and fell in love with her. Those books don’t have her face on them.

The thing that was funny about the TLS review was that the review made a big deal about her looks and how they’re inseparable from her writing, and yet the photo that they ran was not Clarice Lispector. It’s this photo—there are two ersatz Clarice Lispectors floating around—an actress named Rita Elmôr. I explained this in the letter, but basically she did this monologue where she played Clarice Lispector, but it is super exaggerated. It’s this exaggerated image of a woman with a cigarette looking really sultry and deep.

The difference to me between a fake Clarice and a real one is that there really is something hypnotic and self-possessed in the real Clarice’s gaze. I think that beyond her beauty – it’s something that I find more compelling than her beauty—she does have a way of looking at the camera that is very commanding. And I don’t get that same sense from these fake Clarices. The other fake one is this woman named Alice Denham and I think she wrote a memoir. She’s something of a writer, an actress, but also a Playboy bunny. So the picture that’s floating around of her is her being super sexualized, with a huge cone bra, sticking her breasts out, standing over a typewriter and smoking a cigarette. Lapham’s Quarterly used that. They ran that not in print, but the online site used that as Clarice Lispector, and it made me really upset. I’m the only one! I’m sitting here writing to these publications to just not grab things off the Internet without checking.

MB: What’s your initial reaction, too, when you see them? Do you just sigh and then write the letter and get on with it or is it always a bit frustrated?

KD: I cringe! I know it’s an uphill battle and I kind of laugh at myself because a lot of people just don’t care, but I care about the truth. I cringe because I think it’s become kind of this caricature of her. It makes her into this caricature of a beautiful woman with deep thoughts, smoking a cigarette. And she is so much more than that. It’s so startling.

Also, her writing is so seductive and so voluptuous and sensual itself. So I see why people would get obsessed with the person of Clarice Lispector. Even if her writing is not overtly autobiographical, it’s very personal. You really get a sense of this person on an intimate level and she had such a distinct point of view on the world. But I also think some of her stories are outright erotic. They’re sexy.

In The Via Crucis of the Body, there’s so much stuff about the body, there’s so much sex and so much sexual desire, body parts, bodily fluids. But even before that I think that there’s something very physical and sensual about her writing. She’s been compared to Nabokov, and that to me is one thing in her writing that makes me think of Nabokov—this kind of sensual beauty, or even brutality in the words. That might connect to her glamor as a person, but it might also exist separately from it.

I’ll just add one thing though. The reason why I have a mixed view is that there’s a possible feminist standpoint you can take, saying her looks don’t matter, who she was doesn’t matter. Elena Ferrante is anonymous, and everyone’s obsessed with her. We have no idea what she looks like. Her writing is so sensual, so embodied and seductive, and we have no idea. We can just kind of imagine. It’s almost better to imagine what she might be like than to actually know. You know more details about the actual person, but on the other hand, I will say I understand, because we have all these photos, and we know a lot about the life of Clarice Lispector, in one sense, it’s great to have literary heroes and worship them, in a way. Sometimes that worship involves having a poster up of them in your room.

MB: Do you have a poster of her in your room?

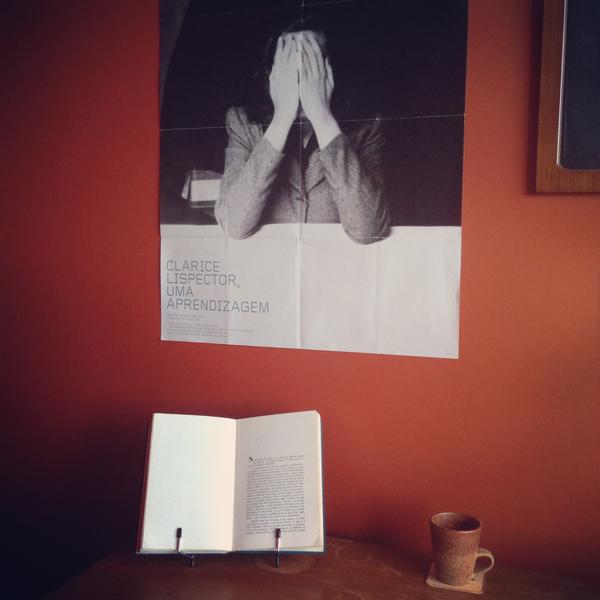

KD: Here’s what I’ll tell you. It’s interesting. The whole time, the two years I’ve been translating, I moved three times, and every time I always had a poster of her up above my desk. It’s a poster of her covering her face with her hands. Her presence is there, but I love that she’s covering her face with her very elegant hands. The person is there, the body is there, but I think of her going inside herself when she’s writing. But it’s also this gesture of anguish. In some ways, I think she was there in solidarity with me as I was translating.

MB: What a beautiful talisman.

KD: Yes! I was asked recently if I had any rituals while I was translating. I said, “not really.” I had some crystals, I would light some candles sometimes just to get me through. I’d say the one constant was having her presence in the room with me in that way.

Do you know the translator Margaret Jull Costa? She’s one of the major translators from Portuguese into English. She does all of José Saramago and Eça de Queiroz. She does more writers from Portugal, but I was reading an interview with her and she talked about her translation schedule. It was insane to me, I was so jealous. It says she wakes up really early, then translates for four or five hours. Then, she takes a swim in the middle of the day, she always has a swim. Then, she has lunch. Then, she sits at her desk again and translates another five or six hours. I’m probably exaggerating. But good work habits.

MB: One last question. It’s a little bit more general and relates to your experience in translating. I wanted to end with one of her best-known quotes from Hour of the Star. Clarice says, “So long as I have questions to which there are no answers, I shall go on writing.” I wanted to flip that statement into a question and pose it to you.

Do you have questions about Clarice’s language and writing to which there are still no answers, and do they inspire you to go on translating more of her work?

KD: I have an infinite amount of questions that have no answers about her work. It’s what I love about her. I had to come to a moment in the translation process where I had to tell myself to let go of the fear of error. That comes very much from Clarice Lispector. I think in her writing there’s kind of an ethics of error, where she doesn’t want to be perfect. Perfection the ideal is all an illusion.

I quoted this already, but in “The Egg and the Chicken,” it says, “Understanding is the proof of error.” It was very difficult to translate her because she’s so important. I knew this was a really high-stakes project and I didn’t want to make a stupid mistake. I’m sure there are some basic mistakes in the translation, and I’m sure there are things that I didn’t quite understand, I might have misinterpreted. But I think that’s just how we’re all human. That’s how it has to be.

I actually went to an astrologer psychic. As you know, Clarice Lispector was very interested in the occult. She writes about a psychic at the end of The Hour of the Star. I went to see the psychic, for other—I won’t say much about it, but Clarice Lispector came to the reading. We invoked her. And you can say it’s the Clarice Lispector in me, there’s no explanation for it, but I will say the way the psychic was talking about her were shocking to me because she was saying things about her that I haven’t read anyone really say about her.

[The psychic said] If you got it perfect, that would mean you would be her, and she doesn’t want you to be her. It would mean that she wasn’t a complex person. In my own head, and also coming out of this experience, I felt that I had to let go of her a little bit, to let the work breathe. This is kind of coming full circle because you had asked about distance. In one sense, I got closer to her than I’d ever been before in translating her, but I had to give the translation a necessary distance in that I had to let go of the idea that I could understand it perfectly and I could translate it perfectly in order to just let it breathe on its own a bit more intuitively.

At the end of the translator’s note, “I’ve given you the Clarice I hear best.” I did want it to be clear that, even though this is the Complete Stories, of course, you’re never going to find the definitive voice of Clarice Lispector in English. They’re all approximations. I think that’s why it’s so great that we have more than one translator working on the series. Also, now we have the luxury of having more than one translation of a lot of these stories.

*****

Katrina Dodson is the translator of The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector. Her work has appeared in Granta, McSweeney’s, and Two Lines. She holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Berkeley.

M. René Bradshaw is Editor-at-large, UK at Asymptote. She was born in California and lives in London.

Read More Interviews: