A story that can be retold and rewritten, but can all the while retain its own thingness—a story that can evolve in the imagination—is a finger in the face of the insipid outpouring of gifs and memes we daily consume, like Technicolor marshmallows shot out of the all powerful maw of the Facebook-Disney machine.

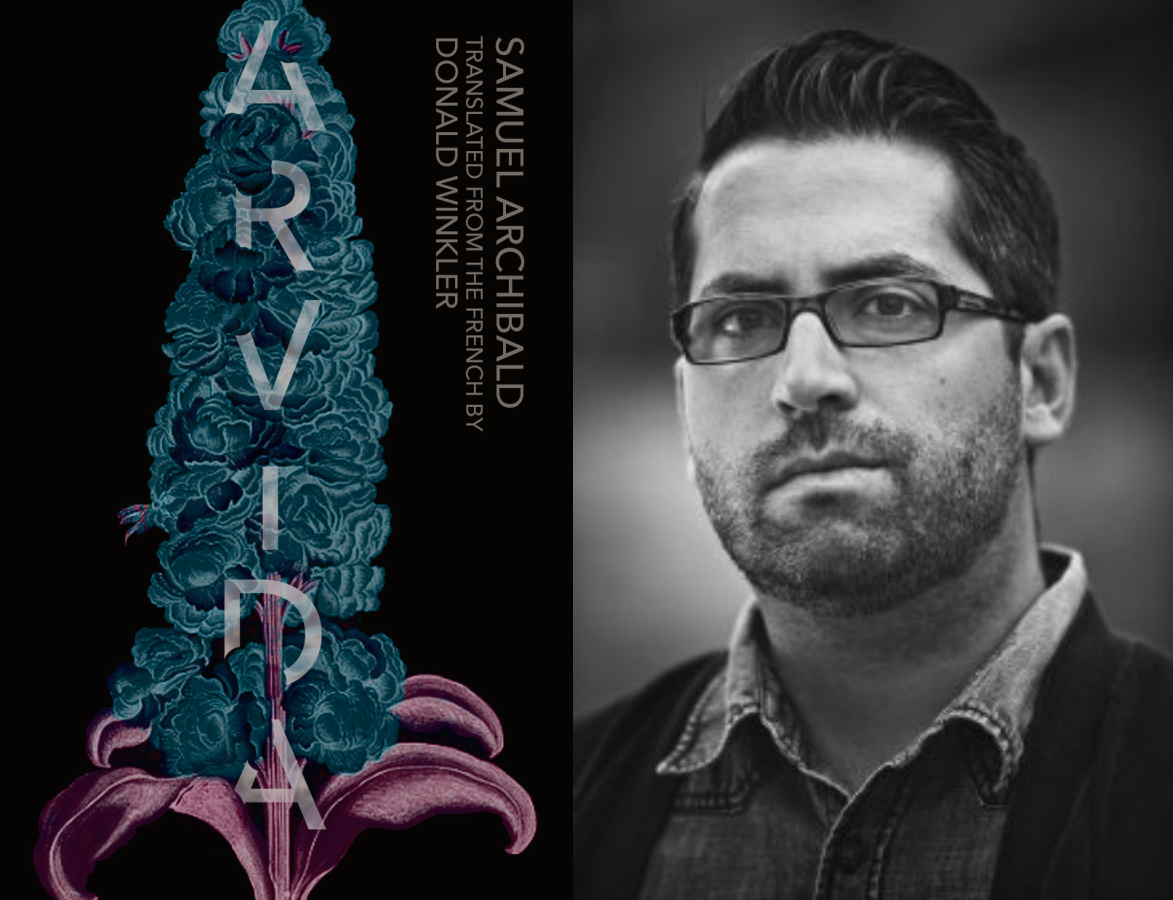

We of the lower forty-eight are fortunate, then, that something like Samuel Archibald’s Arvida, has been recently translated from the French by Donald Winkler. We need stories. And these stories from a land we’ve all been living alongside our whole American lives will do nicely. These are American stories. But another America, a hidden America, maybe even more American than the America we think we know.

Canada. In Archibald’s Arvida, there is an echo of some of the wavering visions we have of our northern neighbor (evergreen, flannel), but they are woven into the fabric of a working-class town, both factual and fabulous, immediately calling up comparisons to Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin’s evocations of Winnipeg. Both Maddin and Archibald tell their tales utilizing a personal history of a family and a discreet location, while at the same time breathing into them a dream logic and fairy tale or fable-like tropes.

But while Maddin’s film dialect can range from the truly bizarre (I’m thinking of his wax museum of live hockey players in “My Winnipeg”), to the hypnotic fever of his latest film “The Forbidden Room”, Maddin’s work is a hallucinatory triumph, chock full of erotic and comedic depth, Archibald’s stories work in a more two dimensional plane.

The mediums of writing and movie-making aside, Arvida is successful as a collection because the two types of stories in it work together in conjunction. In one corner are the Arvida stories. These are stories of the town of Arvida and its inhabitants, most told in the first person. The author seemingly entangles his own family history into that of the town. In this town there are collective memories—a father fetishizing pastries seductively named “may wests,” because of a childhood of not enough to eat, the last born grown-up children of a dying town, imbeciles and innocents, vaguely criminal, and a lineage of hockey, glorious hockey. These are all of a piece.

The second type of stories in the collection are the real beating heart of this Canadian town, and are the stories that make it a very worth while read. Beginning with “Cryptozoology,” we are introduced to Jim. An Arvida boy, through and through: handsome, tragic, equally handy with gun or ax. We are in the woods now. Sometimes there is snow on the ground. In this story, reality begins to get a little confused. The boy is feverish, begins to take on the characteristics of the big cats and wolves he hunts. Later, “In The Fields of The Lord,” Jim is cousin to a little girl, her grandmother has an identical twin and is a sorceress like you play bingo on Thursday nights, matter of fact. In a blueberry field, the little girl dreams of dances with her cousin and he kills himself there, hints of incest in the fields of the lord. Then there is “The Animal.” A little girl full of fear is violated nightly by a nocturnal intruder that looks a little like her father. On the foggy bank of trauma there seems to be some kind of connection between the boy Jim merging with the animal and the girl in “The Animal.”

It is not clear where one story begins and the other ends, or where the animal begins and the man ends. A captured black bear called Billy is also emblematic of that confusion, calling to mind the cursed prince in the fairy tale “Snow White and Rose Red,” when the prince in the bear’s body cries out to the two lovely sisters teasing him, “Snow White, Rose Red, don’t beat your lover dead.” The fairy tale archetypes are rampant in these central stories—grandmothers, woodsmen, young maids in the woods, and the sexual predators who hunt them. Contemporary takes on the Perrault tale of “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge.” I’m thinking of this frightening Neil Jordan romp from 1984, “The Company of Wolves,” and Polish filmmaker, Walerian Borowczyk’s,1975, “La Bête.”

Donald Winkler’s translations of the terms of endearment used here, which probably don’t sound out of place in the French, are wonderful and only add to the odd atmosphere of fear (“my babies,” “my lovely girl,” “my beauty”). In “Paris In The Rain,” the girl is grown up into a different kind of sexuality, a fierce animal independence, a survivor with a history of violence. In the midst of these “Blood Sister” stories is “Jigai,” a foreign girl transported to Japan. Faraway, yet mirroring the Canadian landscape, a context is created for this surgical geisha fantasy. The women taking control of their own pain and their own pleasure.

In Arvida, Canada is “a creature that hides for the pleasure of being tracked, and shows itself from time to time to revive its own legend.” A lake is not named because no one goes there. These are stories that can only evolve in the imagination, and stories that can do that are a kind of true sustenance. Years ago, on some airplane somewhere over the middle of the country, I sat next to a boy covered in intriguing tattoos. To pass the time he began to tell me the story of each one. On his chest were inked two large wolves facing each other. A Cherokee legend has it, he said, that an old brave once told his grandson about a fight between two wolves, that goes on inside of everyone. One wolf is evil, and is all manner of jealousy, anger, and false pride, the other is good and joy and peace. The boy asked his grandfather which wolf wins the fight. The grandfather said—the one you feed.

*****

Gnaomi Siemens has a Bachelor of Arts from Columbia University and is an MFA candidate in poetry and literary translation at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming at thethepoetry.com and Slice Magazine. She lives in New York City with her son.

Read more from Reviews: