Happy Sunday! Today, we continue with our spotlight on our Close Approximations contest by showcasing the first edition’s winners. If you’re interested or know someone who might be interested, bear in mind that we’ll be awarding $4,500 total in prize money to six emerging translators, and our deadline closes in just sixteen days. Visit our contest page for full details.

The second of our two runners-up in the fiction category, Rhonda Dahl Buchanan, gives us this prize-winning translation of an excerpt from Mexican author Alberto Ruy-Sánchez’s Poetics of Wonder: Passage to Mogador.

What a thrill it was to see a sample of my translation from Poetics of Wonder: Passage to Mogador by the Mexican writer Alberto Ruy Sánchez, published in the January 2014 edition of Asymptote—complete with the beautiful Arabic calligraphy created by Caterina Camastra for the English translation of Nueve veces el asombro and an excerpt of the author reading a passage from the novel in the original Spanish.

I believe this recognition helped Dennis Maloney, editor of White Pine Press, secure a PROTRAD grant from the Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (FONCA). With funds from FONCA’s Program of Support for Translation, Poetics of Wonder was published in July 2014 in the “Companions for the Journey” series of White Pine Press. In September 2014, Alberto Ruy Sánchez and I were invited to Washington, D.C. by the Mexican Cultural Institute to present a bilingual reading of the novel, and we’ve been invited back to D.C. by the Mexican Embassy for an encore book presentation this March.

Shortly before Christmas 2014, Texas Tech University Press published my translation of the Argentine writer Perla Suez’s novel La pasajera in their Americas Series, titled Dreaming of the Delta. I hope that being selected as a winner of the Close Approximations Competition will help me secure grants and publishers for future translation projects. I am truly grateful to Howard Goldblatt, Lee Yew Leong, and the Asymptote editors for this honor that truly has been the gift that keeps on giving!

—Rhonda Dahl Buchanan, Runner-up in the fiction category, Close Approximations

The City of Desire

Preliminary Offering

Burning Words for Lovers

That moment had arrived when the lips of lovers ache from devouring each other, and even the touch of the wind reignites their senses.

At that hour, more than any other, words may be volatile sparks that, out of nowhere, perhaps from the air filling each vowel, rekindle the fire in their blood time and time again.

For lovers are as fragile as paper to the ardent caress of certain words.

Lovers gaze at each other with their fingers, but trace and touch one another with their mouths.

Lovers listen to each other even in their silence.

Lovers describe and reinvent one another, coining phrases that shine like new as they cross their lips.

The words of lovers are things, ethereal objects that suddenly flare and beat to the temperature and pulse of the body.

Words

And then, from the table where they lingered before their first kiss and whetted their appetite for conversation, delighting tongues and palates, where hours before two mouths closed around a single fruit, from that table, the lovers took the word saffron and transformed it into yet another instrument for caressing each other.

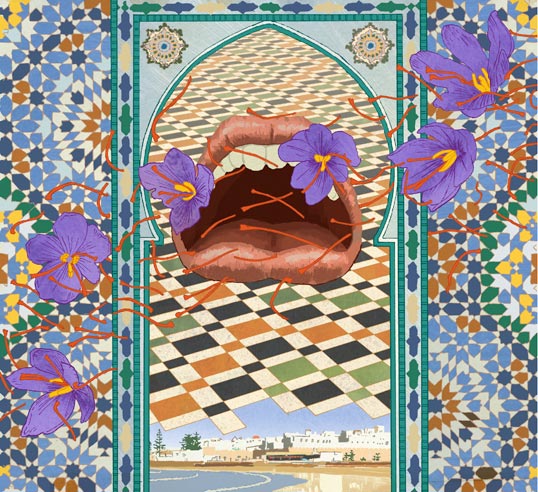

Saffron: bound to the delicate pleasures of the palate and the enduring beauty of the Alhambra. Two dimensions of a culture devoted to the senses, that of ancient Al-Andalus, where the word was pronounced Zaffaraán. Saffron, with its curved filaments, is an arabesque whose spiral comes from a flower and unravels in the mouth.

Their lips and fingers became stained with those blushing amber notes as they rode a wave of tiny kisses, pinching each other ever so slightly, just as they had seen the majestic purple flower gleaned in the fields, its three stigmas plucked by nimble fingers gathering the true red gold: saffron. Only three strands to each flower. And as it takes thousands to produce a few ounces, the lovers pinched each other in equal measure.

Saffron was and is the name of a treasure. But it is also known to be poisonous if consumed in excess. The most expensive and painful poison, although some would say the most delectable as well. Saffron overwhelms the senses, illuminating lovers as if they carried a sun within. Then it rises to the head, soon taking over the entire body, provoking neither hallucinations nor torment, but rather an excess of pleasure.

Even their gazes assumed a more radiant splendor from the word saffron. And wherever eyes, fingers, and lips lingered over the naked, beloved body, an ephemeral tattoo remained, a yellow or orange trail, visible only to the lovers for one meticulously prolonged instant.

They became tinged with burning desire for each other, and finally one of them made a colorful confession: “Your voice makes me feel saffronized.”

With the chosen word, they were tracing a new map of love, an amazing geography of desire to tantalize their senses. And they continued their journey, unfolding and exploring “the saffron route” over their bodies.

Saffron

From the same table, moments later they served themselves the word aceite, oil. One of the lovers, the smiling Hassiba, proposed it, evoking its Arabic origin as it slipped past her lips: azzayt. And the sound she uttered conjured the image of a small pitcher tipping its spout ever so slowly. The word spread, dense and fluid, smooth and mellow, and from its syllables there arose a fragrance that filled the air and attacked the tongue: pervasive but not sweet or salty. Oil.

Then they wished to intensify that rare sensation, and suddenly a special oil came to mind, one extracted from the fruit of the argan, a tree that grows at the edge of the Sahara. It is rather small, like a bush, but with very deep roots. Its bright green foliage stands out among the ochre hues of the desert, lending an air of mystery to the arid lands of northern Africa. It is a distant cousin of the huizache and mezquite trees whose semblance graces the deserts of northern Mexico. They are very ancient trees classified by scientists as “voracious” because their roots grow faster than their leaves and may become twenty times larger than their trunks and branches. Lovers dream of growing inside each other that way, with an excessive voraciousness to the twentieth degree, with a surging thirst in their most intimate veins, rendering them oil by the end of the day.

Argan oil is slightly darker and more golden than olive oil. It smells and tastes like its seed, known as “the nut of paradise,” and leaves a fragrant sensation that scurries through the mouth and nestles unmistakably in the back of the palate. Some nomadic tribes consider this oil an aphrodisiac that arouses in those who taste it an immediate and persistent urge to make love. Oasis oil, oil of paradise.

By then the lovers felt the word oil was more than a taste upon their lips; a second skin, nearly transparent and liquid, coating the mouth ever so lightly and leaving a trace wherever kisses were planted.

Oil, with all its vowels, slithered down the skin of the neck. It mounted the muscles of the chest and circled the granular nipples, softening and stiffening at the same time all those obstinate and unbridled parts that tingle at the slightest touch.

Oil makes the hands sail as if blown by the wind and the skin feel caressed by what has yet to draw near: a breath, a shower, a presence.

Oil lulls and plummets, arousing lovers deep inside and inciting the darkest hunger of their flesh.

Oil

From that slippery lethargy, with lips ever more sensitive, Hassiba half-opened her eyes and slowly cast her gaze beyond the table, past the strands of saffron on the small blue ceramic plate, over the little pitcher of oil with the drop on its spout, above the bread crumbs and the glasses tinged with wine. She fixed her gaze on the fountain that trickled ever so softly against the wall, listening intently with her eyes.

From that fluid vision there sprang from her lips, clear and fresh as water, the word zelije, or azulejo, names for the finely glazed ceramic tiles covering the walls. The lovers found themselves surrounded by hundreds of tiles, a geometric universe that dressed their skin with prismatic forms, casting naked reflections at the same time, like distorted images in an Impressionistic mirror. The room, patio, fountain, and columns formed one sensitive body of which they were now a part. A body made of light and colors: ceramic skin. A harmonious arrangement of modulating forms alternating between them and the world.

In the intense heat, the discovery of that cool skin awakened them to the contemplation of their new essence. They fell in love again with the marvelous composition that was transforming their loved one before their very eyes. Their hands were zelijes stirring the air with each movement. Their eyes azulejos reflecting their smiles. Their fingernails, fierce tiles digging into backs with a clamor.

Each part of their bodies changed into distinct geometric forms, pieces that fit together like the tiles on the fountain wall, creating a perfect abstract painting, an invitation for deep mutual exploration. And their gazes could now embark on an inner voyage, fervently touching the fragile essence of the invisible. The word azulejo transformed them into an enraptured geometry.

Tile

They savored each word that rose to their mouths, surveying its depth with all their senses, prolonging each one in the body, until suddenly one of the chosen words appeared to be more tattooed than the others, filled with more meaning and mystery. And that word grew so much in their hands that it slipped between their fingers. It was made of water, smoke, light, and time. It was the word Mogador.

Another idea, I do not know which, made them think of Mogador and pronounce her name by chance, almost simultaneously. They came upon her by different paths, as if she were a part of the desired body that lovers can never resist.

It was the name of the port where Hassiba was born. And she thought, among other things, that Mogador was the culmination of the words that she and her lover had been relishing: oil, saffron, clay. Somnambulant words if ever there were any.

Like ghosts, there rose before her eyes the walls of Mogador, tinged the color of saffron, where they faced the ocean. Like other sleepwalking phantoms, scattered groves of argan trees came into view, beyond the ramparts, forming a sylvan necklace, a verdant wall uniting and separating Mogador from that other sea that is the desert. Finally, there crossed Hassiba’s mind other slumbering spirits rising behind a veil of steam: the blue-tiled walls of the public bath, the hammam, the ritual center in Mogador of nearly all that concerns the body.

The word Mogador struck Hassiba’s lover as an enormous mystery. Having never been there, it was not easy for him to understand his lover’s fascination for her labyrinthine city, and yet, during restless nights, he had told Hassiba that whenever they made love, it felt as if he were visiting Mogador.

Naked amidst visions of saffron, oil, and tiles, he thought only of Mogador, his head filled with questions and vague images. But does Mogador really exist or, as some claim, is it the name of a woman described as a port? Why do they say she always seduces but can never be possessed completely? Why do they speak of her with wonder? Why do they call her the city of desire? Is it true they count by nines there because the number ten does not appeal to them?

And so, that afternoon at the edge of the sea, while the sky slowly turned a brilliant purple hue, Hassiba, grand gardener of Mogador, began to tell her lover, with captivating words, the things she knew about her city.

Mogador

Although she did not mention it at that moment, the sunset hues reminded her of the remote origin of the city, when the neighboring islands were once called the Purpuraires. Indeed, they have been writing about Mogador since ancient times, many centuries before our era, when the Phoenicians invented an alphabet and writing, and settled on the Atlantic isle of Mogador. That is why some poets say Mogador is as old as the written word and the walled city is actually a letter of the alphabet that remained adrift, floating on the horizon.

The Phoenician alphabet, a unifying and practical force, reached the far corners of what was then their world, and later left its mark on the Greek alphabet, and on the Latin and Hebrew as well. Based on recent excavations, which unearthed some very beautiful ceramic pieces engraved with Punic or Phoenician characters, archeologists have been able to prove that Mogador is the farthest Phoenician port to the west of Carthage. Amazingly, their inscriptions reveal some stories about the city still told in the main square of Mogador, also known as the Square of the Snail.

It was because of a snail that thrives on its shores, that the fortune of this city began to be written and known around the world. The Purple Snail secretes a liquid that, before the invention of artificial dyes, was used to tint the most expensive fabrics in the world. And so, besides the beauty of the place, the Phoenicians found on this and other neighboring islands they also called the Purpuraires a natural dye that at the time was more valuable than gold. For many centuries, only emperors had the privilege of wearing purple tunics. They say an immense flag of that color waved over the most ancient wall of the port and was an extravagant and excessive luxury.

Many centuries later, the Romans circulated throughout their empire a book whose very scarce copies were so widely read and passed on by so many hands that unfortunately not one remains. They called it De Re Mogadoriana, which literally means Things Concerning Mogador. Supposedly, that book, also known at one time as Poetics of Wonder, was a primary influence on the work of Plinio Apuleyo, that Roman from northern Africa who traveled incessantly and made Carthage his home. He is the author of two essential Mogadorian books: Discourse on Magic, and more importantly, Metamorphosis or The Golden Ass, a tale considered to have had a profound influence, more than a thousand years later, on Cervantes, as well as Boccaccio. We can say that the imagination of both authors was sprinkled with a light dusting of Mogador.

Mogador

Hassiba, who bore within her enough of that dust to form a large dune, knew better than anyone the purple trajectory of her city, for as a child she had extracted ink from the snails along its shoreline. With her hands stained purple once again, this time by the evening light, she began to thread for her lover the beads of her tale. A necklace of Mogadorian things emanating from her skin.They are things of air, she told him: ideas, sudden revelations, repeated out loud for days on end, and later in dreams, night after night.

Things that take shape more freely in those transitional moments when one is neither asleep nor awake.

Things such as light lingering over dark skin, music in the folds of the body.

Things that sooner or later become songs, myths, tenacious fallacies, legends, poems of wonder, stories that contradict or complement each other. Or an occasional attempt at scientific hypothesis, equally debatable, of course.

Things that at one time comprised a book.

But no matter how much or how little is attributed to these things, we must remember they are merely what we make of them: stones in a river polished by the water of our hands.

9 tis’atun

These things, regarding what lies within and beyond the city walls, touch on nine themes that have captivated Mogadorians. They never cease to comment on the appearance of Mogador, making observations that are unique and contradictory, often probable or proven, but highly questionable or questioned.

Things like those told about the enigmatic and indescribable anatomic form, seemingly invisible but omnipresent, which the sex assumes in that capricious city fortified nine times over.

Slow or impetuous ways of relishing each moment of time within time; of writing history with clouds; of turning wind into light; of hearing with eyes and hands and seeing with ears the urgent yearnings of the flesh.

Things that run wild and free in the books of a library as if in a meadow. Things passed from one mouth to another, forming a perpetual spiral that retraces the streets of the port.

9 tis’atun

Together, these nine times nine uncertain things they say about Mogador (and a few others) show us perhaps a certain truth: they explain how and how much that phantasmagoric reality, known as the “city of desire,” has grown in dreams and in the waking hours of those who know or envision her, becoming deeply rooted in more than one body.

As you read them, or listen to them (for it seems many have been told or sung in the main square of the port), let some of them grow and beat in your body. May these things multiply in you as they do in the body of Mogador. Because they are like restless seeds:

Unknown fruits that enchant the palate,

stubborn roots,

rebellious rhizomes,

thirsty stones in a dry river,

fish sleeping against the current,

still moving upstream,

birds nesting and flying near the waves,

trailing luster of vanishing stars,

deep echoes of piercing sounds,

endless moans of sighing lovers,

ancient and pristine avalanches,

fading footprints in the sand

trampled by the zealous wind,

images depicted by witnesses,

passionate yet wisely skeptical,

they are the whispers of those things

whose sex blossoms into murmurs

as they continue resonating

and growing into rumors:

they are words, these words.

Words

* * * *

I.

On the Appearance of Mogador

1 ahadun

They say the city of Mogador does not exist, that she lives within us.

But others insist she does exist precisely because she lives within us.

Others, who appear to know much more, which always raises suspicion, claim that Mogador also exists on the Atlantic coast of North Africa, disguised, in more recent times, by an Arabic name to which some attribute magical powers: Essaouira. A name that should be pronounced quickly, as if the vowels barely exist in this word that always sounds surprising: “SsueiRA.” A swift whistling name that has been given three meanings: the well-designed, the one of small walls, the city of desire.

About the first meaning of Mogador-Essaouira, “the well-designed,” they say the calligraphic labyrinth formed by her streets is another magical word, perfect in its geometric design, but unpronounceable by the human mouth. A divine word that can only be read and understood from the heavens. From Earth, it is merely obeyed, like destiny, like the attraction of the planets or the yearnings of the flesh.

About the second meaning of the word Essaouira, “the one of small walls,” I feel compelled to disagree and point out emphatically that her walls are not so small. From the desert or from the sea, they appear like giants defying the waves. But they embrace and harbor their city with such strength and protective sweetness that they diminish and ease the exaggerated concerns and anxieties of her inhabitants so that they may rejoice in the streets and in their houses. And this explains something often heard in Mogador: when they say her walls are small, they are not referring to their size but to the affection they feel for them. They are using a diminutive term of endearment to name them.

For many reasonable and unreasonable arguments, she is also called “the city of desire,” an idea supposedly invented by sailors longing for a welcoming port of call. Or perhaps it was created by those who navigate the other sea of Mogador, that of sand: by the caravans who cross the Sahara, also yearning for shelter and respite. And so, in both cases, she was present in the mind and body of those navigators of salt and sand long before she existed where we presently see her. Even now, when someone approaches her on their long journey, over waves or dunes, they always reinvent her.

They say that even before glimpsing her from the sea, with her dazzling walls speckled by crystalline salt, we recognize her initially on the skin because she is a city that touches us. At times, she does so abruptly, quite often imprinting the senses with a firm but delicate presence that leaves us struck by wonder, first in the eyes, then in the rest of the body, no more and no less powerfully inside than out.

They say upon seeing her, one cannot help feeling passionate about her, and as a consequence, falling madly in love with whomever is close at hand. They say lovers united this way never quarrel or separate, or suffer unrequited love. Discovering Mogador is a binding ritual.

But others say the only ones who can really see her, and only from afar, are those already hopelessly in love, or who at least feel the urgency of a desire that overwhelms them, burns them. They say that in an ancient language of the desert, the word Mogador means “the place where destiny appears”: where the meaning of life suddenly becomes visible because it embodies an ardent desire for the other. They say that a rather indecipherable calligraphy, which the women of Mogador tattoo above the pubis, attests to this small fire that has consumed or transformed some love lives. This is how Mogador appears, behind the flame.

* * * *

[. . .]

IX.

On the Capricious Nature of Sexual Anatomy in Mogador

Seventy-three

They say that in Mogador bodies appear to be, at first glance, the same as in any other place in the world, but when viewed more closely, it is obvious they are quite different, even more so when the gaze is accompanied by feelings, that is to say, when one begins to fall under a spell, in which case distance is not a factor. Something happens that is far more remarkable than penetration or possession: the sexual organs in Mogador create an indescribable field of attraction around them that is beyond words, so much so that speaking of absolute magnetism or primal instinct does not even begin to describe it.

* * * *

Seventy-four

In Mogador, when conversations about the body turn to the sexual organs, the mind skips erratically, affecting language as well, suddenly leading people to describe the invisible realm of the body and its intimate acts. The study of Mogadorian anatomy includes not only what cannot be touched or seen, but also what can be sensed, something that comes naturally there to the involuntary members of that caste known as “the somnambulants,” a special group whose lives revolve around desire.

* * * *

Seventy-five

That is why Mogadorians are perceived as very imaginative and even delirious whenever they speak of their sexual organs. But this is not because they wish to brag or flirt, or express false modesty. They do not boast about any exceptional attributes. Men and women simply think that the most important aspect of their genitals lies within the body, and what rises to the surface is a bit of capricious flesh that dangles or stands up straight, that blossoms voluptuously or withdraws into the shriveled folds of the skin. That is not the sexual organ, but merely its scab, its scar, a glimpse of the true sex that at times may occupy the entire body from within and subjugate all the other organs.

* * * *

Seventy-six

They say the immense pleasure those minuscule parts may provide, compared with the boundless inner delirium that nourishes them, is like a mirage, a sign of something else, an indication that what is important lies much deeper and one must search for it with zeal in the body of the beloved. Those who understand that relationship the sex creates between the invisible and the visible have taken an important step toward happiness and becoming true somnambulants.

* * * *

Seventy-seven

“They think only with their sex” is a saying in Mogador reserved for very few people and used to describe men or women with exceptionally brilliant minds and subtle intelligence who are open, perceptive, adventurous, lucid, and never selfish with their lovers.

* * * *

Seventy-eight

In Mogador, no one speaks of the size of a man or woman’s sex because even though that does matter, it is a question of something malleable that never ceases to change, always capable of surprising or disappointing. The size of the exterior sex is not a quality or designation, but rather a kind of impossible “anatomical verb” conjugated in very different ways by each lover.

* * * *

Seventy-nine

Describing the sex of Mogadorians has always been a difficult undertaking, even for those who attempted to do so in anatomical treatises. Everything becomes confusing in the minds of those who claim to be experts on the subject. In their words, vaginas become flowers opening for the sun, dark images of hot and sultry nights, deep waters that disorient even the most experienced swimmers. Penises are confused with unbearable absences or tender words charged with meaning, with legs, arms, fingers or large noses, with strange puffs of air or trumpet notes in the body, or a cry bursting into a thousand pomegranate seeds, each a taste of infinite pleasure. Often the descriptions of the female sex are also used to speak of the masculine sex and vice versa. Although certainly these descriptions, which may seem somewhat imprecise to some, may actually portray in the most accurate and profound way the true anatomy of the Mogadorian.

* * * *

Eighty

They say that in Mogador there are sexual organs that provide fulfillment to lovers even without penetration. And others that envelop and arouse with astonishing and unsettling perfection, without even the slightest touch. In this port, they refer to the sexual organs as a “somnambulant presence” or “phantoms of the flesh.” This is how Mogadorians describe the undeniable reality of the invisible in matters of the heart, and it explains why they say desire, that mysterious and always surprising and charismatic master of transformations, is the real anatomy of the sex.

* * * *

Eighty-one

In Mogador, the sexual organ considered the most obscene, powerful, and fundamental is the mouth. It unleashes passions, touches, moistens, bites, speaks. No other part of the body rivals its abilities to give and take, to discharge the most intimate of fears and the most spontaneous of pleasures. The mouth reigns over bodies making love, converting all else into metaphors, imitations, and images of itself. The most important things of this primordial port are born in the mouth and die there. This is why in Mogador words are considered the nucleus of the amorous act. They are treated with care, devoured with delight, treasured, and spoken with tenderness. Mogadorians know that sooner or later all the words in the mouth adopt or evoke the essence of the sex. And that is why it is through the mouth that one knows, conjugates, and enjoys, nine times nine, the things of Mogador.

Click here to read the Close Approximations judges’ full citations.

***

Alberto Ruy-Sánchez is the author of books of fiction and essays, which have been translated into many languages, although only two of his novels have been translated to English. He is best known for a quintet of novels, which take place in the Moroccan city of Mogador, and explore the nature of desire: Los nombres del aire(1987), En los labios del agua (1996), Los jardines secretos de Mogador (2001), Nueve veces el asombro: Nueve veces nueve cosas que dicen de Mogador (2005) and La mano del fuego (2007). Since 1988, Alberto Ruy-Sánchez has been the Editor-in-Chief of Latin America’s premier editorial house, Artes de México, which has received more than 100 international awards. In 2000, he was decorated by the French Government as Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, in addition to many other prestigious honors. For more information, visit the author’s website here.

Rhonda Dahl Buchanan is a Professor of Spanish and Director of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Louisville. She has published many critical studies on Latin American fiction and is the editor of a book of critical essays on the Argentine author Ana María Shua. Her translations have appeared in journals and anthologies, and include the following books: Limulus: Visions of the Living Fossil by Brian Nissen and Alberto Ruy-Sánchez (translation of the short story “The Secret Seduction of the Horse Shoe Crab” (Artes de México, 2004); The Entre Ríos Trilogy by the Argentine author Perla Suez (University of New Mexico Press, 2006), Quick Fix: Sudden Fiction by Ana María Shua (White Pine Press, 2008), and The Secret Gardens of Mogador: Voices of the Earth by Alberto Ruy-Sánchez (White Pine Press, 2009), which was supported by a 2006 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship.