Every year since 2009, writers, critics, and literature lovers have been flocking to the Austrian region of Wachau for the European Days of Literature. Late this October, I was fortunate to spend three glorious autumn days surrounded by vineyards in Spitz and Krems on the Danube, to talk about all things literary and listen to authors read from their works, all liberally sprinkled with local Grüner Veltliner. Literature was center stage throughout—and there was a perfect balance between readings, panel discussions, informal chats and the picturesque setting—no wonder many of the participants have been coming year after year.

The overarching theme of this year’s gathering—The Migrants (Die Ausgewanderten)—was chosen with a view to discuss the ways European literature has been changing through and along with the increasing migration of authors. Little did the organizers know that the symposium would take place at a time when migration dominates the media headlines as thousands of desperate refugees risk their lives to cross the Mediterranean and trek through Europe seeking sanctuary, putting the old continent’s humanitarian values, tolerance and unity to a test and threatening the very foundations of the European Project.

“Some of the best writing in Europe today is migrant writing,” said writer AL Kennedy, who tries not to define herself as having a specific nationality. In her powerful keynote speech (podcast recording here) she tackled the current migration crisis head on: “Between my first draft and my last a photograph of a small boy made it to headlines of many newspapers which had, only hours before, been pouring out hatred at refugees as a moral, cultural, biological and spiritual threat. As David Cameron put it: ‘a swarm of people.’ When people are in a swarm, they aren’t people. They are both of an alien species and a danger. When words put them in a swarm, they don’t receive the real world’s help.”

Practising art alone is not enough at times like these, she argued in her impassioned address, for “true art is not an indulgence but a fundamental defence of humanity.” She challenged writers to take on a more activist stand, using tweets, poetry, and bestselling novels, to create “50 shades of refugee.“

AL Kennedy’s call for writerly activism was echoed by Ilma Rakusa, an author who believes passionately that writers have to act as human beings and citizens and that writers carry a greater responsibility because they have a slightly better chance of formulating their position out loud and reach more people. “I was a child in transit,” says Ilma Rakusa in her memoir Mehr Meer. Errinerungspassagen (“More Sea. Passages of Memory”). Born in Slovakia, raised in Trieste and Ljubljana and now based in Switzerland, she does not regard herself as a specifically Swiss writer but rather as a European one and homeland exists for her “only in the plural, homelands” (a sentiment I can fully relate to, having changed countries and continents several times, not always entirely voluntarily). Unfortunately, hardly any of Rakusa’s prose writing is available in English, which makes the forthcoming translation of More Sea by Tess Lewis—soon to be published in the United States—all the more welcome.

Several other writers reflected on their experiences of writing in between cultures. “I am writing from abroad,” novelist Najem Wali says after 35 years of exile from his native Iraq. His homeland is the language he writes in—Arabic, now influenced by German and Spanish, since Wali commutes between Hamburg and Madrid. All of his books have been translated into German: here is a clip of him reading from his novel Engel des Südens (The Angel of the South). Also a naturalized German citizen, Lena Gorelik was born in St. Petersburg and writes in German. She is ambivalent about the label “migrant writer,” and while her early works reflected her Russian-Jewish background, her latest novel, Null bis Unendlich (Zero to Endless) focuses on the former Yugoslavia. Her dual background allows her to play with different images evoked by the same words in different languages. For example, “Apfel,” the German for apple, conjures up the image of a big red fruit while when she hears the Russian “яблоко” she sees a small yellow apple.

British writer of Sudanese heritage Jamal Mahjoub feels he inhabits a twilight zone, perceived as neither Sudanese nor British. From his current base in Barcelona, he reflects the diversity of his background by adopting different author identities: in addition to novels dealing with the history of Sudan he is currently on the sixth of ten planned crime novels written under the pseudonym Parker Bilai.

“For me in-betweenness is a permanent state of life that will never be transformed into any other state,” says Miriam, a character in Other Lives, a novel by Lebanese novelist Iman Humaydan who is based in France but regularly commutes between Paris and her home city of Beirut, driven by curiosity and inspired by travel. She discovers her native country anew every time she visits, and her forthcoming fourth novel, Fifty Grams of Paradise, deals with Kurdish migrants of Armenian origin living in Beirut.

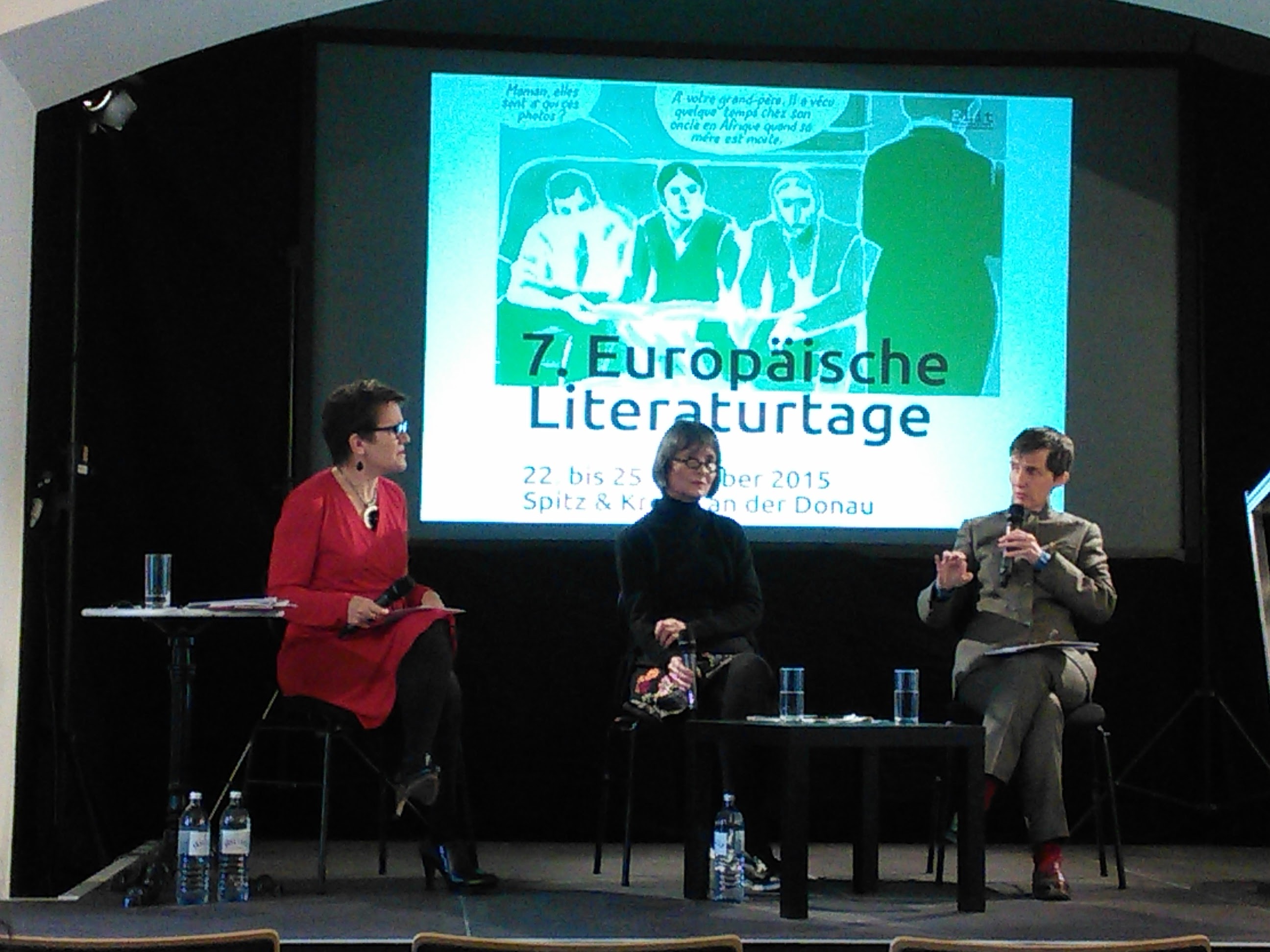

Iman Humaydan also interviewed Paris-based Afghan writer and filmmaker Atiq Rahimi following a presentation of his incredibly moving film The Patience Stone, which he adapted from his Prix Goncourt winning novel of the same title. Comics and graphic novels were represented by Marguerite Abouet, a French author whose phenomenally popular Aya of Yop City series draws on her experience of growing up on the Ivory Coast, and Yvan Alagbé, a writer, painter and publisher of mixed French and Beninese origin whose slide show presentation of his haunting images – in many shades of grey – had a strangely balletic quality.

While graphic novels and comics have long enjoyed great popularity in France, it is a genre that has been slow to gain ground in Germany, Christian Gasser explained on an information-packed panel on contemporary literary trends in Europe. Here are just a few highlights: literature scholar Jürgen Ritte introduced the latest French buzzword “exo-fiction” or novel without fiction, represented by Patrick Deville who (in an earlier session) read extracts from his series of ‘world novels’, a project of staggering ambition, encompassing all the world’s continents and covering everything from the discovery of the treatment for cholera to the building of the Suez Canal.

Critic Rainer Moritz offered a comprehensive list of current trends in Germany from regional crime novels (nearly every German city now has a home-grown inspector of its own), through family novels (e.g. Julia Franck), to fictionalized autobiographies. Several German writers have embarked on major projects, comprising ten or twelve autobiographical novels. Interestingly, this Knausgaard effect seems to have emerged in parallel, rather than in response to, the Norwegian literary sensation.

There has also been a resurgence of the political novel (represented by authors such as Ulrich Pelzer, Ilja Trojanow and Jenny Erpenbeck). This is a trend that literary events organizer and editor Éva Karádi also noted in Hungary (as well as in other Central European countries) where writers had turned away from politics after the end of communism in 1989 but current political developments have brought about a renewed transformation of homo poeticus into homo politicus. Also in the UK, writers, Ali Smith among them, are increasingly speaking up about politics, said Rosie Goldsmith, the indefatigable champion of European literature in the UK and founder of the European Literature Network (a partner organisation of European Literature House). Other UK trends she noted include the rise of fantasy fiction, the resurgence of poetry, the short story revival as well as the growing number of literary festivals and the emergence of small publishers that focus on literature in translation.

Although none of the panels focused specifically on the work of literary translators, given that all the writers present depend on translation to a greater or lesser degree (and some, like Ilma Rakusa, are translators themselves), it was inevitable that the discussions kept returning to translation statistics, particularly the dearth of translations published in Anglophone countries (the latest figures for Europe as a whole can be found in the 2015 CEATL report). And while British and American publishers’ resistance to taking on works in translation has recently weakened, the dreaded 3% certainly applied to the UK market between 1990 and 2012, as confirmed by the latest survey conducted by Literature Across Frontiers (LAF). Its director, Alexandra Büchler, singled out the UK as a ‘peculiar case of insular multilingualism’ (take a look at LAF’s latest project, Literary Europe Live, bringing together literary festivals and venues from around Europe).

Last, but not least, a panel on digital publishing offered fascinating insights into digital copyright and digital book lending, with examples from Slovenia and Switzerland that suggested that small countries are at a distinct advantage when introducing innovative nationwide solutions. This whole area was very new to me—so rather than making a hash of all the technical details, I refer you to the expert summary by László Szabolcs, who blogged about the European Literature Days live together with Peter Zimmermann. (Check out also the Eurolit Network website for more write-ups and visit their photo gallery on Flickr).

*****

Julia Sherwood is Asymptote‘s editor-at-large for Slovakia. She was born and grew up in Bratislava, which was then Czechoslovakia. She studied English and Slavonic languages and literature at universities in Cologne, London, and Munich. She spent more than twenty years working for Amnesty International in London and has since 2008 worked as a freelance translator. She is based in London.

Read More from Austria: