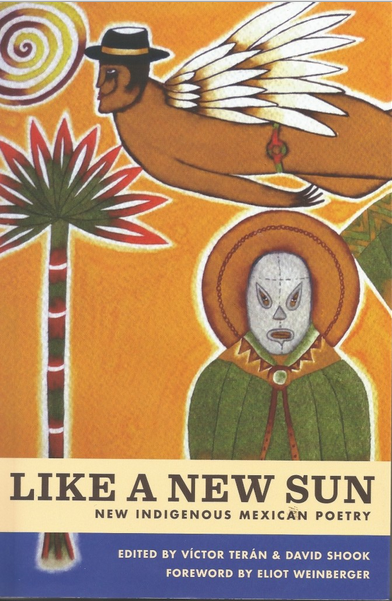

David Shook is a poet, translator, and filmmaker in Los Angeles, where he serves as Editorial Director of Phoneme Media, a non-profit publishing house that exclusively publishes literature in translation. Their newest book is Like a New Sun, a collection of contemporary indigenous Mexican poetry, which Shook co-edited along with Víctor Terán.

Seven translators in total—Shook, Adam W. Coon, Jonathan Harrington, Jerome Rothenberg, Clare Sullivan, Jacob Surpin, and Eliot Weinberger—translated poets from six different languages: Juan Gregorio Regino (from the Mazatec), Mikeas Sánchez (Zoque), Juan Hernández Ramírez (Huasteca Nahuatl), Enriqueta Lunez (Tsotsil), Víctor Terán (Isthmus Zapotec), and Briceida Cuevas Cob (Yucatec Maya). I corresponded with Shook over gchat to speak with him about the project.

***

Today is Columbus Day, a controversial holiday in the United States. Several cities have recently adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day over Columbus Day, clearly a victory for recognizing indigenous cultures in the United States. Which leaves me wondering: how are the indigenous Mexican writers recognized today in the Mexican literary landscape?

As someone who regularly visits Mexican literary festivals and also translates from the Spanish, I’ve observed the under-appreciation of indigenous writers firsthand. Mexico’s indigenous communities make up 10 to 14% of its total population, and you certainly don’t find anywhere near that percentage of literature being published in Mexico today.

There are a variety of complex reasons for that disparity. In 2010, Víctor Terán and I were interviewed by the BBC alongside prominent Mexican poet David Huerta. We had been touring the United Kingdom with him, and he had spoken admiringly of Víctor’s poetry. But when discussing the state of contemporary Mexican poetry—and specifically its influences and lineages—Huerta quite frankly admitted that he believed the contemporary indigenous traditions were separate from the mainstream Spanish-language tradition.

I’ve spoken quite a bit with Víctor about this, and he, as a very political personality, believes there is active discrimination against indigenous voices, an observation I agree with. Although I recognize (without excusing) this discrimination is often more the result of ignorance than any ill intention.

Víctor—and here I quote him directly—intends to write for his people, the Isthmus Zapotec community of Juchitán. He believes that most of the contemporary poetry being written in Spanish today is too disconnected from everyday life to be relatable. All of this is to say that basically the relationship between indigenous-language poetry and Spanish-language poetry is very much one-sided. Víctor, and other poets and writers like him, whether they’re writing in Tseltal, Tarahumara, or Spanish, are actively reading Spanish-language writers, and their work responds to currents in Spanish-language writing. But Spanish-language writers are very seldom reading work by indigenous writers.

There are some recent signs of increasing appreciation, however. Festivals like PoeTiSa in Tijuana have been inviting more indigenous-language writers, and prizes like the Premio de Literaturas Indígenas de las Américas, which in addition to the honor awards $25,000 USD, are helping indigenous writing gain visibility in mainstream Mexican media.

Having read through Like a New Sun, I agree with what you say in the introduction: the poetry is very contemporary. It came to my surprise to see a collection of indigenous Mexican poetry in English, of course, but these poets clearly deserve wider recognition. Is this the first collection of its kind in English? When did we last see an English-language anthology of indigenous Mexican poetry?

There was an anthology edited by Donald Frischmann and Carlos Montemayor in 2005. It’s a great anthology and I recommend it. While it covers a broader spectrum of poets and languages, part of what Víctor and I wanted to do with this anthology was showcase fewer poets by offering a more significant selection of their work, enough so that the reader can get a good feel for their work. A couple of our younger poets—I’m thinking of Enriqueta Lunez and Mikeas Sánchez in particular—hadn’t begun to publish back in 2005. So our anthology is very current.

Víctor has been a mentor to and model for many younger indigenous writers, so it was important to include those up-and-coming voices. And it was nice to showcase the real variety of poetry being written in indigenous languages today.

The cover of Like a New Sun, edited by David Shook and Víctor Terán.

You can hear Mikeas Sánchez read some of her poems on the Phoneme Media Soundcloud page. They’re wonderful—she reads with musical accompaniment. Juan Gregorio Regino’s poems also have a chant- or ritual-like quality to them, like an invocation or prayer. What are these poets’ relationship to the oral tradition, music, and performance?

I think that you see the influence of the oral tradition on the work of most indigenous-language poets, but in different ways and to varying degrees depending on the poet. Juan Gregorio Regino’s work definitely takes explicit cues from the Mazatec oral tradition. He’s also an expert on María Sabina, the Mazatec healer.

What’s really interesting to me is the work being written by younger poets, like Mikeas, who incorporate the influence of the oral tradition alongside very contemporary images and situations, like a plane’s black box, or Senegalese immigrants in Barcelona.

Or the window at a Macy’s store, from her poem “Nereyda Dreamed in New York.”

Exactly! It’s worth noting that Mikeas works as a radio presenter, and that she broadcasts in a couple indigenous languages. So she intimately understands the power of that medium as well.

Her poem “Jesus Never Understood My Grandmother’s Prayers” stands out to me as one of the most emblematic poems in the collection. In the poem, none of the grandmother’s prayers to Jesus work. It’s not until she curses in her native Zoque—jukis’tyt and patsoke—that anything happens.

It’s a heartbreaking poem, on the surface, but ultimately I think it’s also a poem of strength.

My grandmother never learned Spanish

was afraid of forgetting her gods

was afraid of waking up in the morning

without the prodigals of her offspring in her memory

My grandmother believed that you could only

talk to the wind in Zoque

but she kneeled before the saints

and prayed with more fervor than anyone

Jesus never heard her

my grandmother’s tongue

smelled like rose apples

and her eyes lit up when she sang

with the brightness of a star

Saint Michael Archangel never heard her

my grandmother’s prayers were sometimes blasphemies

jukis’tyt she said and the pain stopped

patsoke she yelled and time paused beneath her bed

In that same bed she birthed her seven sons

*Jukis’tyt and patsoke are Zoque swear words.

Mikeas Sánchez, “Jesus Never Understood My Grandmother’s Prayers,” translated by David Shook.

There is a saint that I learned about when I was living in a Nahuatl village in Guerrero. Black James. Have you heard of him?

No!

This will take us back to the reclaiming of Columbus Day. When conquistadors arrived in Mexico, they brought with them the saint Santiago Matamoros. Matamoros, in Spanish, means “moor killer,” and came into being during that time in Spanish history. When they brought him to the Americas, he eventually became Santiago Mataindios, or “Saint James the Indian Killer,” if you will. Mexico’s indigenous population, rather than rejecting this saint, subverted him by making him their own. They darkened his skin to match theirs, and he became a sort of protective saint, Santiago Negro. “Black James.”

It’s worth noting I’m not a historian. This is actually a story I heard in the village, where the local church had a statue of Black James riding a white horse. So now we’re back to the oral tradition, as well.

Well it leads me to another question. Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and God coexist with pre-Columbian gods in the book. Is it safe to say that the indigenous religions are suffering the same lack of recognition as the languages themselves?

The syncretism is incredibly complex. I think it’s fair to say that the Catholic Church never wholly eliminated the different indigenous faiths of Mexico, which often coexist with Catholicism, or appropriate Catholic imagery. It really depends on the region and community, too, and their geographical accessibility. So while they don’t have official recognition, I don’t know that they’re seeking it either, for the most part. And, like anyone else, there are plenty of writers—and people—who identify as agnostic, atheist, and non-practicing.

Like a New Sun is bilingual, which allows the untrained eye to make connections between languages. What is particularly noticeable in this book is the different sizes and shapes some of the English translations take from the originals. Of course, there are six languages represented in the book, all unique. But what were some of the difficulties in the poems you translated?

For Víctor’s work, replicating the sonic texture of a tonal language like Isthmus Zapotec (which employs the frequent alliteration of glottal stops) is impossible. I benefited from a reading tour we did for the Poetry Translation Centre, an early champion of his work in English. We spent three weeks on the road in the United Kingdom, and I listened to him read his poems every night.

Depending on the pairing, many of our translators used Spanish intermediaries, proceeding in collaboration with the poets themselves, who translate their own work into Spanish by necessity. So as an editor I’m on the lookout for poems that cling too tightly to their intermediaries, especially in regards, for example, to the nesting of prepositions, which doesn’t happen in an agglutinative language.

In my own experience as a translator, Juan Herández Ramírez’ poems were a challenge. He writes in Nahuatl, but a different dialect from the one I studied. Still, he writes his poems in Spanish, almost concurrently. He says that the two languages work like mirrors of each other. I collaborated with Adam W. Coon, an incredibly talented Nahuatl translator, to do those translations. They’re all based on traditional Nahuatl corn myths.

One of the things Juan told Adam, in an almost lamenting tone, was that he doubted that English had enough corn-specific language to do the poems justice. So that was our challenge.

I did have to look up what copal was.

You can’t know copal until you smell it!

With my background in linguistics, I’m pretty skeptical of the “billion words for snow” cliché. I think we can all say just about anything in any language. The challenge and the fun of it is to do so as poetically as possible.

Speaking of linguistics: the book clearly serves as both a book of poetry on its own right, but also as a learning tool. Each introduction features a brief introduction to the language, including its linguistic qualities; there is even an online study guide for the book. Phoneme Media itself, of course, borrows a linguistic term for its title.

Though most readers won’t be able to engage much with the original languages, we wanted to pay them their due as a symbol of respect and admiration. Víctor has done a lot to promote the book’s publication in Juchitán. For him, it’s a part of his language activism.

He has campaigned to revitalize the Isthmus Zapotec language by encouraging and inspiring the youth to use it in everyday life as well as in the arts. To him, it’s an important sign of prestige for the community, to show that their language is appreciated outside of their own region. And that the everyday linguistic oppression they might feel from the Spanish language can be circumvented and challenged.

I suspect many casual bookstore readers might not know how many languages are still spoken in Mexico. The sheer diversity is astounding. And to realize the quality of work being written in these languages is even more astounding. There’s so much great work that we couldn’t fit!

Moon. Sweet white moon

like the gleam in the eye of an unlucky hunter

who chases a rabbit across the mountain.

Emptied and moldy cachimbo shell moon.

Pregnant belly moon.

Delirious moon

like a colander that dreams of overflowing with water.

Deformed egg moon.

Rupe rubber-fruit moon:

give me a slice of your joy

to refresh life in my town.

Ceremonial huipil moon

that adorns the Zapotec’s head:

give me the fireflies that live in your heart

to light my people’s paths.

Intact moon, full moon.

Moon happy to die laughing

slapping its ass.

*A huipil is a traditional blouse commonly worn by indigenous Mexican women.

Víctor Terán, “Moon,” translated by David Shook.

It’s no surprise Víctor’s book sold out on the United Kingdom tour you mention in the introduction. His poems are breathtaking! It seems you two have worked closely together now. As a translator of what are some deeply personal poems, what is it like to work with him? Are you able to work closely together on the translations?

It’s always been an honor to work with Víctor. He’s a poet I admire greatly, and his work has definitely influenced my own poetry as well. In fact, there is a poem in my collection Our Obsidian Tongues that is after his poem “I Know Your Body.”

I’d say that I work fairly independently on the translations, although he’s readily available to answer questions, and I believe as a translator—and as a life philosophy as well—that the more questions you can ask the better. Facebook has made our communication much easier, almost seamless.

Translating someone’s poems is, I think, the best writing workshop there is. You see how a poet does what they do, down to the level of syntax and sounds. So I’ve learned a lot from Víctor—although I’d say that the best thing about our relationship is our friendship. We have fun together, and fun is important to me.

You said there was so much great work you couldn’t fit in the book. Should we expect more indigenous Mexican poetry projects from Phoneme in the future?

Definitely! We actually have one book coming out this month, by the first woman poet to write in Isthmus Zapotec: Natalia Toledo’s The Black Flower and Other Zapotec Poems, translated beautifully by Clare Sullivan. It won the Premio Nezhualcóyotl when it originally appeared in Mexico, basically the Pulitzer for indigenous languages, if you will. And our edition is trilingual, with English-Zapotec and Spanish-Zapotec facing pages.

*****

David Shook is a poet, translator, and filmmaker in Los Angeles, who serves as Founding Editor of Phoneme Media. Find out more about his work here.

Ryan Mihaly is a musician, writer and artist living in Western Massachusetts. He is the Interview Features Editor for Asymptote. Read more about his work here.