“So she’s asking the husband what his favorite vegetable is. And she’s cooking it for him,” a male teacher in Banswara District, Rajasthan is telling me in his home. I peer down at my notes. By the end of the session, I’ve realized a peculiarity: the lines he’s given me for the song being translated—grinning all the while—number far fewer than my lines of lyrics. A discrepancy calling for a more concerted effort, more translators, more women to tell their own tales.

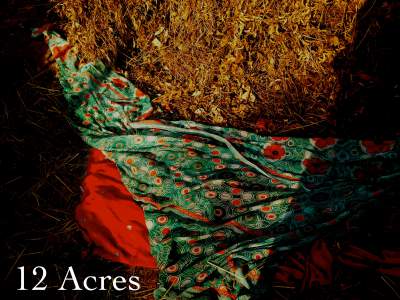

Around this time last year, I was recording and just beginning to be enraptured by Bori Village women’s song-stories in Vagdi, an oral language under threat. As part of the EQUILIBRIUM artist’s residency at Sandarbh, working with women’s self-help economic groups as equals to create new artistic contexts, six songs were recorded by my friends from Bori in a studio—what became “The 12 Acres EP”—transcribed into Vagdi, then translated into English and Hindi, with the help of colleagues. The end goal, however, was to make these songs come to life in a wordless world, a picture book melange of visual imagery.

To interpret song-stories into picture books came out of an observation, as a disabled woman artist myself, of differences in how women’s local cultures were transmitted to women with varied ways of living in our bodies. My friend Santia Patidar is a deaf woman with a hearing son and husband, within a hearing community of women in Bori Village. When I was being completely taken by the songs the women were singing for us visiting artists with force and pride in Rameela Auntie’s house, Santia was making sure I had enough water, and playing the hospitable older sister role with the same authority. And I wondered about whether or not, despite being much-beloved and esteemed by everyone in her community, there existed a gap in storytelling for her, in how she interpreted the songs. I asked Santia and her friends about this, and it had not occurred to them to convey the stories within them to her, or how they might do so—not out of lack of love and respect—and her family and friends began to be excited about the practice of translating between deaf and hearing worlds.

These songs in Vagdi are about women’s relationships to in-laws, love, dreams, everyday life, wants and needs and legends and each other. When they sing in chorus, these women are strengthening bonds with each other, and with a feminist culture that is one of innumerable ones under threat today, if not under extinction. Most men I spoke to in Banswara had no idea what the tales were, let alone their children, fewer and fewer of whom speak and understand Vagdi as time goes on. In this near-exclusivity to women, sung as they gathered together working in the fields or at home, the songs create a safe space. However, as an oral language, Vagdi songs excluded Santia and other members of the deaf community in the district, many of whom in Santia’s generation did not often use reading and writing to communicate, throwing into relief the limits to what texts and alphabets provide them.

The picture books created for three of the songs—in English and visuals, with versions forthcoming in Hindi—are not simplifications, but interpretations. Picture books are stigmatized as children’s literature, because children’s literature itself is stigmatized. Yet the women of Bori Village understood what a boon it was to have books that their non-Vagdi-proficient children could use in schools and among themselves, to understand what their mothers and grandmothers were singing. By providing books that can be used to share women’s song-stories with deaf and disabled women, we are providing accessibility in manifold ways: access to the stories for them, but also for their children and husbands and daughters who do not speak Vagdi or have access to the contexts in which the songs are sung, and to all who do not read or write or do so very little. Accessibility is often like this—access has its way of multiplying, of providing unexpected understandings and connections.

Here I should add that as a disabled, brown woman, I loathe the use of “them” to indicate a community of which I’m not a part of as potentially silencing of that community, assuming that “they” are people to be helped. I am a hearing person, not of the deaf community, and I use “they” here not because Santia and the women I met are silent, passive “target beneficiaries”, but simply because they are women who communicate best not through reading and writing, and I am acting as interpreter, limited and flawed, of our experiences together.

“Twelve Acres” is not about the woman’s husband. In fact, the teacher neglected to mention an extremely important fact about the song: the husband in the tale is a lantern. The lyrics are below, with a sample of two of the illustrated pages of the book, and the song itself in audio form. In my lay interpretation, as a woman who’s worked with and listened to this song innumerable times now, it is the story of how a woman is nudged into an unfulfilling marriage, and the simple, rapacious craving so many women the world over feel—for more. Satiety and hunger of the appetite are also that of emotional fulfillment, of feeling enormous in a world that tries to keep us small.

After my work in Rajasthan, I asked my mother about her local village’s language, Bahasa Lintau from West Sumatra, and about its words and songs that only women use. It filled me with anxiety that I knew so few words from this matrilineal culture of which I am a part, living so far from the contexts of village life where women’s songs are sung for strength. It made me miss what wisdom my cousins and I could have gotten from them in our times of need, in carefree moments, in friendship.

When we lose individual local languages, we are losing gendered understandings of each word and story. We are losing contexts in which women support each other with stories that to men may be about a husband, but to us may be about power in ourselves, loneliness, endurance, strength, joys and troubles that are specific to our experiences. When we relegate individual deaf and disabled feminist communities and women to the marginal, we are missing out on a plethora of diversity and opportunity to strengthen people and cultures.

The opening up of translation into different accessible formats, stories in formats accessible to an infinite variety of bodies and minds, is not “charity work” that casts us disabled women as pitable souls to “be empowered”. It is opening doors into possibilities for feminists to explore, together, the communities and stories we have to protect. As communication in new media proliferates with ways to gain access to other ways of being, but also to amplify the voices of only those with power, how can we investigate accessible translation as a way of being that dignifies individual cultures, including deaf and disabled cultures?

It’s an exciting journey. Like the Patel woman in “12 Acres”, we could drink the water of seven oceans, and it still might not quench our thirst to make language exclusion—and extinction—a thing of the past.

“12 Acres”

From Vagdi, with thanks to Bori Village women and Sandarbh.

The peacock is singing, and a woman dressed in finery walks down the path.

Seven female friends come together and go to fetch some water.

On their way they meet a lantern, grazing cows.

He asks the Patel woman, “Which village do you belong to, and are you married or single?”

The Patel woman answers, “I am single and not married.”

“Go and tell your father that a lantern is coming to marry you.”

The archway of the [marriage] door is made of swords and sheaths.

Somehow their hands are tied in a marriage knot, but the lantern looks small.

Somehow they do circumambulation, but the Patel woman looks bigger than her groom.

250-200 elephants are gifted to bid farewell to the couple.

The 25 kg sickle has a 15 kg handle.

She cuts the grass of 12 acres of farmland, and makes of it one big heap.

Five to 25 people are called to lift the crop, but they fail.

The Patel woman then sits on one knee, and lifts the heavy crop by herself.

On her way home, she thinks of which vegetable to cook.

On her way home, she sees some bitter gourd. She plucks it and makes her saree full with it.

On reaching home, the mother-in-law thinks to help her by lifting the grass.

At the same moment that the mother-in-law attempts to lift the grass, she falls.

“Son, the daughter-in-law has today used up all my energy from all these years,” says the mother-in-law.

The Patel woman goes in the courtyard and puts the grass down, and there are 12 heaps of grass.

The Patel woman puts the bitter gourd down in the courtyard, and they are so many that they pour from the house.

She makes rabdi in 12 pots, the vegetables in 13 pots.

She eats half of what she makes, but it only satisfies half her hunger.

She drinks the water of seven oceans, but it only quenches half her thirst.

***

Khairani Barokka (b. Jakarta, 1985) is a writer, poet, artist, and disability and arts (self-)advocate. Among her honors, she was an NYU Tisch Departmental Fellow for her Masters, an Emerging Writers Festival’s Inaugural International Writer-In-Residence, and Indonesia’s first Writer-In-Residence at Vermont Studio Center. Okka is the writer/performer/producer of deaf-accessible solo show “Eve and Mary Are Having Coffee”, which premiered at Edinburgh Fringe 2014 as Indonesia’s only representative, with a grant from HIVOS. She was recognized in 2014 by UNFPA as one of Indonesia’s “Inspirational Young Leaders Driving Social Change” for “raising awareness of disability through inclusive arts”, and has been awarded six residencies, with a seventh upcoming. Published in anthologies and literary journals in print and online, Okka has presented work in nine countries, is co-editor of forthcoming HEAT, an anthology of Southeast Asian urban writing (Buku Fixi Publishing, 2016), the author of a forthcoming poetry-art book (Tilted Axis Press, 2016), and a PhD candidate at Goldsmiths. www.khairanibarokka.com / @mailbykite.