Ugly Duckling Presse is a nonprofit publisher for poetry, translation, experimental nonfiction, performance texts, and books by artists. Matvei Yankelevich is the co-founder and co-executive director of the press, and Rebekah Smith is an associate editor who spent the summer in Buenos Aires. We chatted over Skype about the press’s origins, as well as two of its translation series: EEPS (the Eastern European Poets Series) and Señal, which Rebekah and Matvei both curate.

Alexis Almeida (AA): I want to first ask about Ugly Duckling’s origins. I read recently that you started as a zine and over time evolved into a small press. Can you highlight a few major transformations that the press went through during in this time? What were you goals for the press initially, and how have they changed over the years, especially as you expand to include more collective members and publish new kinds of books?

Matvei Yankelevich (MY): Well, it’s important to say first that the press has very little to do with what the zine was, although the name stuck. When I moved to New York, I kept using the name for new collaborative projects with people I met. When we decided to actually do something more substantial, in the late 90s, we were just a group of writers, artists, and theater people. It wasn’t necessarily going to be a publishing house, but we decided to keep the name, Ugly Duckling Presse. What united us, or gave us the idea of working together, was that we were making books with each other, or for each other, so books were a common language. And the original idea was that we would publish things, maybe have a space, have performances and shows, but that was very difficult in late 90s New York.

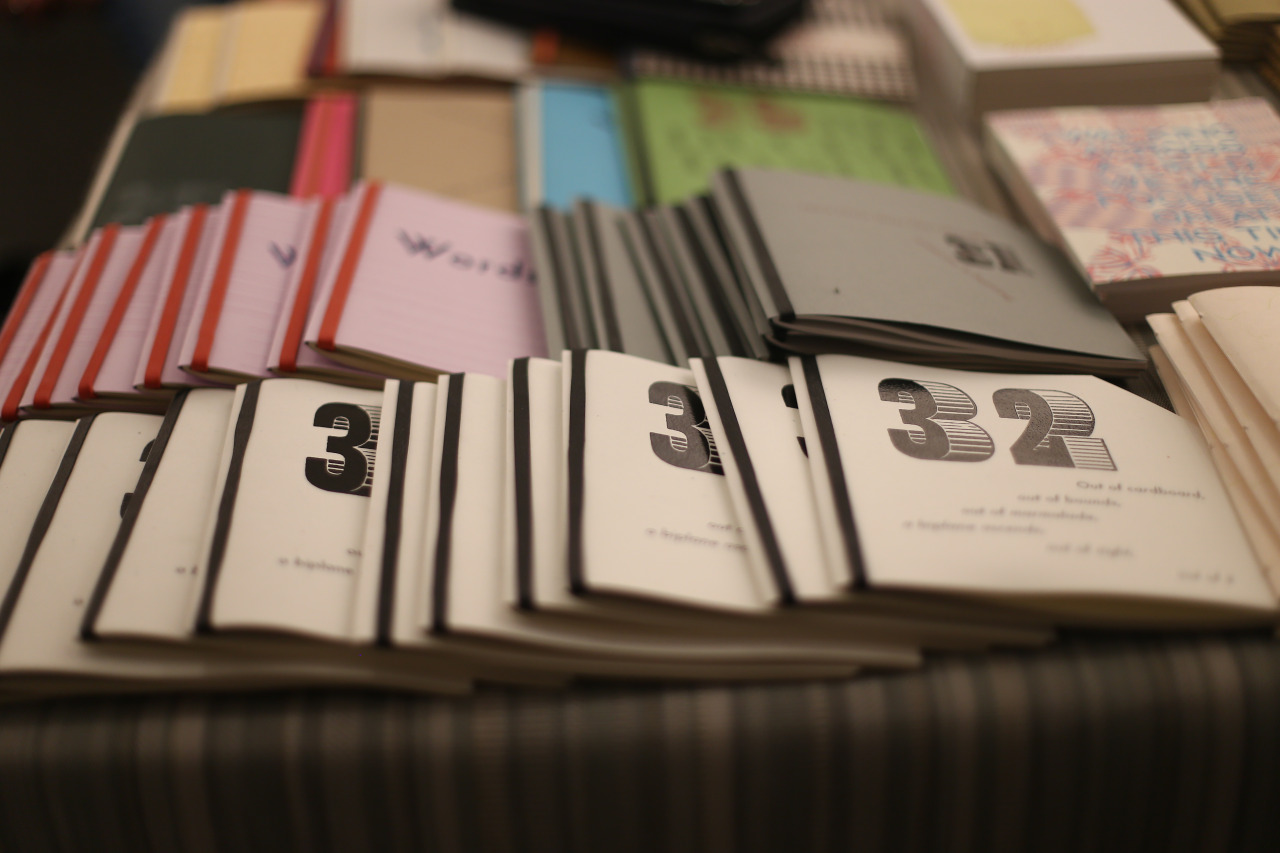

But the publishing side of it really became the focus. In the late 90s we did a couple of smaller projects, and in 2000 we started doing larger circulation things: 6X6 (a tri-annual publication that features six poets who each contribute six pages) started at about a thousand copies of each bi-weekly issue. We distributed it for free. That was a new magnitude for us. We also did an Emergency Gazette about theater—we did about a thousand copies. And we were also doing some chapbooks.

But things changed in 2002 because we got a space. We weren’t in anybody’s living room anymore, and that allowed us to have more events, and equipment to produce more. It was a place where people could meet and talk and come up with new projects. That was also around the time we were turning into a non-profit and starting to write grants, so that allowed us to do some of our first books, or our first large-scale projects, like the Eastern European Poets Series books, the first few poetry books. Then we couldn’t move back into anyone’s living room, and that really precipitated the change. That was 2002/2003.

And the collective also started to change. Some people wanted to just make chapbooks they didn’t have to account for, they didn’t want to get an ISBN number and such. So around 2005 some people stopped working with the press. When we did 0-9 James Hoff was involved, but then he went off to start Primary Information, because what he wanted to do specifically was reprint books from the conceptual context that had gone out of print. So the press branched off, and some people went off to do other projects. And then a core of us, maybe five or six people, stayed. And other editors started joining. It still keeps changing in terms of focus. And in terms of who the staff is, and how we imagine the connection between the staff, or people who work on administrative tasks and the editorial collective, and there is a continual conversation around how to make that work.

The second major change was when we sold the collection to Yale’s Beinecke collection, and we were able to start our first paid managing position, and that was in 2009. So we hired one of our interns as the manager for a while and that really changed the way things were functioning here, for the better.

AA: Something I admire about UDP is the diversity of the books you publish—of course in terms of aesthetic, genre, country of origin—but also the quality of the books themselves. Your emphasis on the hand-made seems to not only draw attention to the labor and history of bookmaking, but also the labor and history of the small press in general. Are there any presses you consider to be predecessors or inspirations for UDP? Has there been a kind of model for the work you do, and has it changed over time?

MY: Early on we started trading books with Burning Deck, and Burning Deck was a big influence, at least for some of us. But over the years there have been many influences. The Emergency Index kind of comes out of this magazine High Performance from the 70s (we basically took that idea from a section of that magazine), and 6X6 was designed as an homage to a Russian Futurist magazine, so there have been a lot of little influences.

For me, artist books, especially democratic multiples, are a big influence. And also there are certain European presses that we steal ideas from, certain classic series. I remember early on we got this whole package in the mail from some Mexican neo-futurists—they found out about us in 2001—and they were printing all these newsprint-type things, and this shoddy letterpress, and the aesthetic was really beautiful and punky. So a lot of influences came to bear. Especially alternative weeklies from the 60s, like the East Village Other. Some of us are influenced by special edition kind of stuff. And small presses like Coracle that do a lot of letterpress, and can be playful with book structure design. And we’re also very influenced by constructivist design. Rebekah might be able to say a bit about this, because she joined the press by just coming in on presse days [book binding days open to volunteers] and doing a lot of chapbook binding and stuff like that.

But I do think that in the moment of the late 90s, peripheral things were starting to professionalize—there were glossy, bound magazines instead of stapled magazines, etc. There was a New York Public Library show around that time that was really influential. Jerome Rothenberg and Steve Clay edited a book about that exhibition, Secret Location on the Lower East Side. There was a lot of mimeo stuff, a lot of fast publication, and that was a big influence on a bunch of us who went to that show. We were all interested, but maybe we didn’t know as much. There was something about the informality of the fast publication in the poetry world, especially the mimeo revolution, fast turn-around, simple design, this was really important to us—and still is—because the arts are so professionalized. With desktop publishing everything started to become more alike. As a friend of mine said, you can go to Barnes & Noble and see a thousand miles of the same book. There was something happening with digital publishing, a kind of leveling was going on. So I think something interesting about being a small press and having to do things expediently was that we had to do a lot of things ourselves, and use really simple technology to do it.

Rebekah Smith (RS): Yes, like Matvei said I started with UDP by coming in on presse days and just binding books, and on my first day—I think I was sorting type—I said, this is the best place I’ve ever been. You get to make things—I like working with my hands—and there’s great literature and translation, so many languages floating around, the people are nice, and there’s coffee! All these things added up for me. I worked in bookstores during the rise of Amazon, and you get the same question almost twelve times a day: what are you guys going to do? One of the things that small presses do during the age of Amazon and e-books is give you these beautiful objects that you want to hold and touch. I think the fact that our books are beautiful but not too precious is fantastic. I just showed someone here [in Buenos Aires] some of our books today, and he was really impressed. Small presses here are not necessarily making their books the way we do. I think our design is really beautiful and really important—they stand out.

AA: Okay, I’ve already mentioned UDP’s emphasis on a diversity of genre, but there are a few specific translation series I’d love to talk about, particularly Señal and EEPS, or the Eastern European Poets Series. Señal, co-run by Antena and BOMB Magazine, is a fairly new series, meant to highlight Latin American poets. What can you tell me about it? I’m really interested in hearing about Stalina Emmanuelle Villarreal’s translation of Sor Juana’s Enigmas, and John Plueker’s translation of Luis Felipe Fabre’s Sor Juana and Other Monsters, which reimagines Sor Juana as a literary figure in various historical contexts.

RS: Yes, well, we’re sort of going a new direction this year, but in general we’re reimagining what contemporary means, and there’s this brand new translation of Sor Juana. Fabre is contemporary, young, and also dialoguing not only with her but also her reception, the way she’s talked about, etc. So it’s both a reimagining of her and her work, but also the status she has as a poet within Mexican and Latin American culture. And I think it’s very funny—it’s a great book. And I think J.P. did a really great job with the translation.

It’s funny, whenever I try to explain Señal—I was trying to do it in Spanish today—I say it’s a series dedicated to contemporary Latin American poetry, and people ask who we’re publishing first, and it’s Sor Juana. So this is very interesting to me, that part of the “contemporary” is re-defined by a seventeenth century poet being re-translated by a Mexican poet and translator, living in Texas.

MY: I think Rebekah’s right. We found Stalina Emmanuelle Villarreal through Jen Hofer and John Pluecker, and they thought she would be great for this project. So there’s definitely the thing that Rebekah is talking about—the contemporary re-imagining—but we also wanted to think about what it means that Fabre is engaging with Sor Juana in a way that involves contemporary social issues, rather than the study of a classic. So then there’s the question of what we could publish alongside that. The idea that publishing work of Sor Juana’s that is enigmatic or difficult shows why she is still interesting today, and I think it creates a really great tension.

The series started because Brenda Lozano, a Mexican novelist who I met through the writer and translator Gabrielle Jauregui (whom in turn I met through Mónica de la Torre and Jen Hofer), started brainstorming with me about a project we could do together for UDP. There were a lot of possibilities for Señal—should this be a series focusing on contemporary Mexican writers? Should it be wider than that? What are the parameters? Because I don’t speak Spanish, and I don’t know the scene, I suggested that we get other people on board, and getting the support of BOMB (and Mónica de la Torre), and Antena (with John Pluecker and Jen Hofer) would create a fruitful conversation. Now that we’ve widened the series to take on the idea of the “contemporary” in Latin America, we’re asking if we should be thinking thematically, or taking on social issues, or in the case of the second year looking at things like small presses in specific cities, in this case Buenos Aires. And we’re thinking about the connective tissues we’re drawing out with these selections, instead of only looking at the most important writers from particular countries, or simply moving around the globe. And we’re also looking for groups of writers from the early 20th century that might take on some resonance now, might further allow us to question the idea of the contemporary. And even in the future, thinking about Latin American languages other than Spanish. And questioning the way Latin America is construed as a singularity—we’ll see what we can do about playing with those expectations.

RS: Yeah, I really look forward to branching out from beyond just one country next year, and finding other connections. Speaking across borders. Like Matvei said, making it a bit confusing to figure out what the connections are. For next year, two books from one country—Argentina—worked out, and I’m really excited about focusing on small presses. And in addition to having a push toward finding people who aren’t being published in English, we also are working with people that haven’t translated a lot before.

MY: I think there’s an interest among the editors in finding new translators, allowing the work of new translators to shine, as well as more obscure work. There’s really just not a lot of dialogue between North America and South America in terms of publications, and there are so many vibrant scenes. We’ve talked a lot with people in South America who are interested in UDP books, and it would be nice to reciprocate and bring some of that work here.

The whole series falls in line with UDP’s goal to privilege translations as we become more established. Translations are harder to sell, but as we are able to have more publicity for the books, I think it’s a better time to do translation than it was in the past, when it was harder to get people to pay attention. Because more people know about UDP now, it’s easier to present them with authors they’ve never heard of. Pairing up with these organizations [BOMB and Antena] allows us to make these books available in Latin America for distribution, and eventually we’ll pair up with some organizations to bring some of the writers here for a launch or reading tour.

So on to EEPS, the Eastern European Poetry Series. EEPS has been around for much longer, since 2003. Browsing the catalogue I’m finding bilingual editions of contemporary Eastern European poetry, work from avant-garde poets whose work is not widely available in English translation, and I’m seeing a recurring theme of re-publishing, re-discovery, reclamation, finding work that has been obscured for various reasons, has been out of print for a while, or has not found wide distribution or availability. This also seems to be a theme in the forthcoming anthology “Written in the Dark: Five Siege Poets.” Can you talk a bit about this issue as it pertains to this series? What were your initial aims for this series and how has it evolved?

MY: Well the series began pretty organically, and it was pretty happenstance that I got certain manuscripts. But they happened to be the manuscripts I was really hoping for. We had happened to publish some Moscow conceptualist work in the magazine, and I had been interested in sharing it with friends here. I got a manuscript of Dmitri Prigov and a manuscript of Lev Rubinstein in the first year or two. And those were really important for me and for the series. I was also interested in what peers were writing in English, who came out of a Russian émigré experience, and how different it was, how different they were from each other. I’m also interested in poets writing in English, where the poet’s first language is not English.

I feel like now the series is moving more towards reclamation projects. We have a 19th century poet that’s never really been published in English that’s coming out now—who was a really important poet at the time of Pushkin. And we also focus a lot on minor poets, with different kinds of histories, or poets who were for one reason or another not heard, even in their own language. I’m also interested in the parallels between the small press in the U.S. and samizdat in Eastern Europe, and other underground art traditions. And we’ve done a lot related to that. Also contemporary writers that don’t fit the mold of the prize-winning writers in post-Soviet countries, where prizes seem suspect. We don’t usually choose writers who are in all the anthologies. I’m really interested in single-author collections, but recently we’re doing collections of small groups—not really in the vein of “best-of,” but more in the old sense of the anthology, of somehow belonging to an album or a group.

So yeah, I try to stay away from the obvious things. And if it’s a name that’s known, to do something unusual. Doing Tomaž Šalamun’s early books was very important for me, because those had been excerpted in English translations, but they’re really interesting in terms of what he did in the 60s and 70s, and how it went against the grain of what was being written, and how it opened up so much space for other Yugoslavian writers. And it doesn’t make sense unless you look at the original sequence of the book. When work is taken out of its social context it really doesn’t make as much sense. Anthologies tend to be de-historicized—people just think “these are really good poems!”—and I’m really interested in bringing back the situation from which the poet is coming, what they are reacting to, and networks of connections that made things that way.

We did a big Vsevolod Nekrasov book, and we’re doing someone who was a friend of his, a strange writer, Igor Kholin, who was part of the same underground group, and there are echoes there. And also Lev Rubinstein’s work—there’s an echo there—he’s circling around that grouping. And similarly with Slovenian, we’re going to do a book by a writer who was kind of a cult-leader, a kind of strange mystic that Tomaž Šalamun really recommended. He doesn’t seem to fit into any categories, and again, he’s not someone that would appear in a best-of anthology.

And we’re really excited about Written in the Dark: Five Siege Poets, because those poets never showed those poems to anyone when they were alive. Polina Barskova [editor of the collection] is an incredible researcher of that time period—particularly the blockade of Leningrad, from 1941-44—and an incredible editor. And that’s really exciting to me, because these were people who wrote in a way that was sui generis to that space, and never wrote like that again. It can become a bizarre record of the time. And we’ve been able to draw connections between the work in this collection and later poets we’ve published in the EEPS series, continuing our interest in late avant-garde experimental work.

RS: Yes, I think Matvei said it all. But also I was thinking about how EEPS is such a diverse pooling. Baratynsky, the 19th century poet that Matvei mentioned before, isn’t known as well as Pushkin, but he was—is—great. I’m excited that we’re publishing the first representative English-language collection of his work. And then there’s a collection from a group called Orbita, in Latvia, that are writing in Russian. They’re contemporary, and they’re a collective doing performance, video-art, visual poetry, and all sorts of things in Riga. They’ve been around for about 20 years, and while they’re pushing limits with poetry and video and art, they’re also drawing on European Russian, Latvian traditions. And the poetry is great. We’re also publishing Vladimir Aristov, who is contemporary and working in the meta-realist tradition, and the Siege book. To me, it seems like a very diverse group of books that we’re working on. And for someone who wasn’t around UDP from the beginning, I think it’s a terrific series. I like that it’s work that wouldn’t necessarily be published by other people, that is somehow unexpected, or written by people you may have assumed you knew everything about but didn’t.

*****

Alexis Almeida received her MFA from the University of Colorado. Her recent poems, essays, and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in TYPO, Vinyl Poetry, Tupelo Quarterly, Heavy Feather Review, Oversound, and elsewhere. She is an assistant editor at Asymptote and a contributing poetics editor at The Volta. A finalist for the Fine Arts Work Center fellowship, she was recently awarded a Fulbright grant to Argentina. She lives in Denver. ![]()