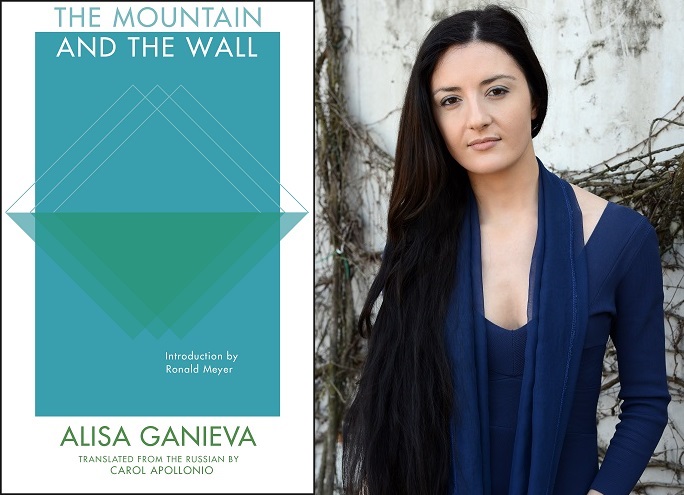

Last month, Alisa Ganieva was in Iowa City to teach global literature in English and the Russian-language workshop of the Russia-Arabic session of Between the Lines, a summer program for writers between the ages of 16 and 19 who spend two weeks in shared cultural and artistic dialogue about the literary traditions of their home countries. I sat down with Alisa to discuss her rise to literary fame and the new translation of her novel, The Mountain and the Wall, out this month with Deep Vellum Publishing.

At 24, you won the prestigious Russian literary Debut Prize of 2009 for your novella, Salaam, Dalgat!, which you wrote under a male nom-de-plume. How did you choose “Gulla Khirachev” for your pseudonym?

My goal was to hint those from Dagestan that I’m not a real author. That’s why I took a real name, “Gulla,” which means “bullet” in my mother tongue—in Avar language—but has not been used for many years. I found out there is actually an old man called Gulla, but he might be the only man with this name. So when my Gulla Khirachev appeared, many of those in Dagestan—journalists and writers—guessed that it must be a pseudonym, and they began trying to find out who it was. They guessed there must be a person, a young man, who lives in Makhachkala, since he knows it so well. They argued with each other and named different candidates, but always missed.

So you meant for the name “Gulla Khirachev” to be transparent as a pseudonym?

Yes, so the name means “bullet,” and the lexical root of this surname means “darling” in my native language. So it’s something piercing, but at the same time, it’s something . . . nonaggressive.

So even the Russian critics knew it was a pseudonym?

No, they didn’t. It is all the same for Russians—Magomedov, Khirachev—they don’t know the difference at all between all these strange surnames.

You studied criticism, rather than fiction, at the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow. Did you always intend to write fiction, or did you suddenly reorient toward it?

I always intended to write fiction, but I realized that I wasn’t ready at 18 or 19. I didn’t have enough experience; I had lots of desire, but there wasn’t a particular topic; I hadn’t read as much; I didn’t have the confidence to begin my own fiction. I thought it would be better to know about other peoples’ texts, about theory of literature, to analyze and learn to analyze texts, developing a censorship within myself. Sometimes it’s difficult for a beginning writer to destroy her written pages: when you put so much energy and assiduity and hard work in your pages, it’s hard to say no, it didn’t work; I have to cross it out. So yes, that was a strange entrance into literature from the side door, not the main entrance.

Do you now feel yourself more a critic or a fiction writer—or both?

Many people still call me a critic, but I don’t think of myself as one, because a critic has to read everything that comes out: the main books, you must know all the tendencies in Russian and world literature. I don’t have enough time and sometimes I don’t have enough discipline or desire to read as many books as I used to as a student. So I’m not a critic. I’m interested in contemporary literature, I read my colleagues, and sometimes I write reviews, even articles, but that doesn’t make me a critic.

Since you’ve studied criticism and you’re aware of the need to be critical of your own work, do editing and writing play into each other for you? Are they complementary?

I think yes, they are complementary, because every author has to recognize her weaknesses. I know my weaknesses, so I try to strengthen those parts of my work. For example, I’m not good at long descriptions, and that’s why many people say that my works read like screenplays: there’s lots of dramatic action and dialogue, and you can easily see and imagine what’s going on, you can hear the characters talking.

So I tried to turn this—my disability of building long, descriptive parts—into my ability, into a thing that is usually praised by critics. But in The Mountain and the Wall, the descriptive parts are not my own: they’re my characters’. So these literary hoaxes continue when I’m giving my characters an opportunity to express themselves with too much pathos. Perhaps in a sense, I’m ashamed to express myself that way without my characters. So it allows me some psychological breadth.

I feel a Dostoevskian influence in your crowd scenes, in the way the political rabble-rousers yell over each other and gesticulate, each voicing a conflicting opinion. Is Dostoevsky an influence of yours?

Yes, because I particularly like these places in Dostoevsky’s novels where everybody is jammed in one room, shouting or discussing something. Maybe sometimes it looks too hysterical and unrealistic, but nevertheless, this way of shutting several characters in a closed space really provides lots of opportunities to you as a writer to develop the plot, the consequences of events, and to show the collisions.

In The Mountain and the Wall, you excerpt other fictional texts into your text. Did you strive to give each of these interpolated texts its own literary style?

I felt greedy writing this novel because I wanted to realize the multitude of voices in Dagestan and express them all—but you can’t do it by yourself. Your characters must speak for themselves. That’s why some parts of my text sound like magical fairytales where I’m telling about different mythological realities of ancient Dagestan, like pagan and agricultural and carnival Dagestan. In other places, for example, there is an excerpt from a socialistic novel, and there is a poem and clips from a sharia newspaper, so there were different styles. That’s one way of including many voices besides dialogue.

It’s said a writer in English can have only one dream sequence in her entire career, but dream sequences are a staple of Russian literature, and several vivid dreams occur in The Mountain and the Wall. What is the function of the dream sequence for you in your writing?

So the mountain that appears in the shared dream of two characters in my novel symbolizes past agriculture in the Caucasus. This past is largely unknown in the Caucasus of today, because they substitute new history and traditions with something superficial and perfunctory and alien, like Arabic culture or global consumerism. But they still don’t want to know anything real about Dagestan itself. Many young people don’t speak their native languages, for instance, and they’re too lazy to learn them. They’re not interested in maintaining them.

At the same time, they think of themselves as big patriots in Dagestan. They’re wearing T-shirts like this . . . [indicates her Iowa sweatshirt with a laugh]. But it doesn’t coincide with real actions, this perfunctory patriotism. Still, it’s quite sincere. If I say something un-lofty, maybe not speaking in superlatives about my motherland, they become really angry.

They write letters saying that I’m damaging their image. And this patriotism is typical not only of the Caucasus, but of Russia in general, because Russia is like an animal that wants to frighten another animal and shows his tail. So we made the Olympic Games in Sochi very showy. All the holidays in Russia are held with greater patriotic zeal than they used to be even four or five years ago. Some symbols of Soviet culture are on their way back, like the “friendship of the nations” ideal that was the slogan of Soviet times. At holidays, young people dress in the national costumes of different Soviet republics. So everything is returning now.

On the other hand, it affects the situation in Dagestan quite positively because the TV news blocks about Dagestan are not as negative as they used to be, those which led to a negative conception of persons from the Caucasus especially in the early 2000s. There was a lot of bad news about the Caucasus because it was profitable for Putin to indicate a problem: claiming an enemy to fight, insisting that he’s making real progress.

Now the ideology has changed. Now we all are brothers fighting against the West, so we must all combine our efforts, we must make friends with each other. That’s why there are lots of positive reportages on TV. So when the annexation of Crimea was announced in Russia, they showed meetings from Dagestan, for example, where people supported the issue. To some extent it plays a positive role, so Russians are not as aggressive towards people from the Caucasus in Moscow. When I first moved to Moscow, I was frequently stopped by police in the streets because of the way I look. When they saw that my permanent address was not in Moscow but Dagestan, they led me to their police offices, though it was illegal because I had all the documents: I was in my country’s capital, I was studying there.

Would you say a few words about your relationship to your translators?

I’m very happy with my German translator Christiane Körner, who is very diligent and asks about every detail, every word. I have lots of work to do when she’s translating, but it’s worthwhile, believe me. We have Skype talks and she sends me sheets of paper with lots of questions and underlined words and expressions. Many times I have to send her photos because I can’t explain some things which are particular to the Caucasus.

When translating dialogue, she said that she used the slang of Turks living in Berlin to dispatch these shades of meanings, of sounds in colloquialisms. So the narrator’s language is quite neutral; and in dialogues, there’s this slang of Berlin Turks.

Carol Apollonio made the wonderful translation for the American audience. Of course, she had lots of problems to solve. For example, she asked me: “How could it be that the spring—the source of water in the village—is embellished? How can it be embellished if it’s just water coming out of the earth? And she translated it as “a well.” I wrote her that there are no wells in mountain villages; there are springs. They are built like—it was hard to explain it—constructions: beautiful, with stones and everything. I sent her photos, and she translated accordingly—“an ornate structure built over a spring”.

Last year, Carol came to Moscow to participate in an international conference of translators from Russian. There she met Christiane and my French translator Veronique Patte, who was also in the process of working on The Mountain and the Wall. We had a couple of very productive rendezvous.

The funniest thing occurred with one Chinese professor, who’s now training in Moscow. I met up with him a few times on different occasions and mentioned that my first novella, Salaam, Dalgat!, had been translated into Chinese. He was very enthusiastic to learn this, inquired after the name of the translator, and discovered that it was he himself. Imagine, he didn’t even remember having done it! And he never got in touch with me during the translation process because he thought I was male, so there was no reason!

Would you say a few sentences about your newest novel, The Bride and The Bridegroom?

Compared to The Mountain and the Wall, there are fewer plotlines, and they are less intricate. But it is written from two points of view. I’m writing in the first person for the first time. So the narrator is this girl, a potential bride, and from an omniscient perspective we also follow the boy who is the groom. The beginning of the plot—it sounds quite absurd for both Western and Russian readers—the boy’s parents want him to marry. So they give him the list of brides to choose from. They have already leased the banquet hall for the wedding. It costs a lot, because Dagestanis usually invite 2,000 guests, most of them relatives. All of them bring money, so in some way it is compensated, but not all the way.

And you have to do it in advance, because a wedding is a crucial point in everybody’s life, and all the businesses there revolve around weddings: lots of beauty salons, wedding clothes salons with Muslim and secular clothes; banquet halls, magazines dedicated to wedding planning. So that’s the beginning of the plot: he has to find a wife, and the date of his wedding has already been assigned, but there’s no bride yet. That’s the melodramatic side of the plot, but it’s not a melodramatic novel as such. My novels are not only about love. There are always social, religious, and even mystical problems arising.

***

Alisa Ganieva is a Moscow-based fiction and essay writer from Dagestan. A graduate of the Maxim Gorky Institute of Literature and Creative Writing, she won the 2009 national Debut Prize for her first novel, Salaam, Dalgat! Two more novels have appeared since then: The Mountain and the Wall in 2012 and The Bride and Bridegroom in 2015. Her stories, articles, and reviews are widely published and anthologized. Recently listed by The Guardian as one of the most talented young Muscovites, she’s distinguished by major Russian literary prizes.

Genevieve Arlie is a writer, editor, translator, and perpetual student from California. She previously served as Editor-in-Chief of Exchanges, the literary translation journal of the University of Iowa, where she was an Iowa Arts Fellow. Her awards include a Pushkin Poetry Prize, a Stanley Research Grant, and a Kathryn Davis Peace Fellowship. This fall she will be the 12-week Writer-in-Residence at the Iowa Lakeside Laboratory.