“What is the Burmese word for cockroach (kar-chwa)?”

Auntie Moe Moe interrogated in a mixture of Mandarin and Hokkien dialect. My brother glanced at me haplessly as I rummaged through the repository of my memory, biting my lips as my live-in domestic helper, nanny, and aunt tapped her feet impatiently.

There it was. “Po heart.”

The romanization under my childish scrawl appeared in my head, and I triumphantly recited the two syllables hiding beneath my tongue.

*

The new millennium’s early years were tentative; there was too much that my ten-year-old self had yet to encounter. Life remained confined to the safe spaces of my suburban neighborhood in Singapore, and I barely ventured beyond the boundaries of my island city-state, except for occasional weekend trips to neighboring Malaysia.

But those days of growing up with Auntie Moe Moe—who hailed from Myanmar and whom I looked up to as a second mother—had also imbued me with an unconscious awareness of alternative languages, cultures, and histories alongside my own.

*

I watched her from the corner of my study room as dusk fell at the end of a school day. There she was: hunched over a table, etching out words in Burmese script in long letters she would send home. Sometimes, for dinner, we tucked into a spicy salad of beans and rice tinged with lemongrass and vinegar while Auntie bit into a baby chili as if it were a ripe, juicy mango (that did not make your lips swell for hours on end).

She did her daily chores to the thrum of a Burmese cover of Madonna’s “Take A Bow.” At night, while my brother and I slept, she moved her fingers along her rosary bracelet and uttered a prayer for us before the poster of Buddha plastered on the bedroom wall.

*

Singapore and Myanmar blur at the hazy edges of my memory. Auntie knew neither English nor Mandarin when she first arrived on our shores, but learned enough phrases from dinners before the 7 p.m. soap opera on the Chinese channels to be mistaken as our mother when we went grocery shopping together in the neighborhood stores. Some evenings, we closed the doors in my room and thrashed our arms around to a litany of techno dance tracks from our “Best of 1999” album.

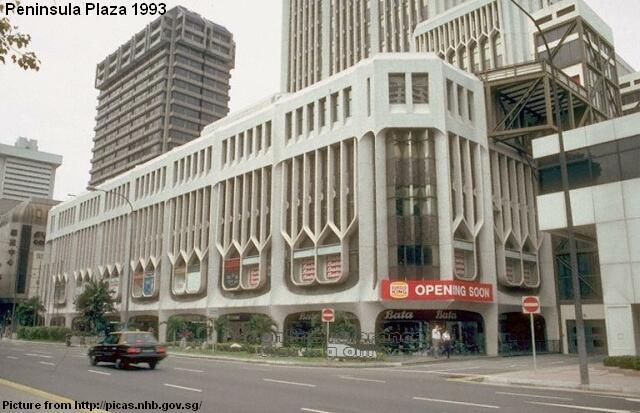

Sundays are days off. Occasionally, she brought us along with her to the Burmese Buddhist Temple, or to the Peninsula Plaza—the shopping mall near the financial district where the Burmese expatriate and migrant community liked to gather, roving past racks of longyis and jars of thanaka face cream.

*

We said goodbye to her for the final time when I was eleven years old. I continued to bury my head in books about the Second World War, or coming-of-age tales set in distant locales—China, India, Europe, the United States. As I ventured further and further away from Singapore after my A-level exams, taking university classes in literary and film studies—first in England, and then California—the Burmese words Auntie taught me continued to flit away at the recesses of my mind. As a pivotal experience in childhood, these memories of her, in the words of the artist Teresita Fernández, continue to exert a subtle, subterranean hold over me.

*

I wandered through neighborhoods of Paris, Rouen, Venice, and Florence on trips during term breaks. There, lilting accents and unfamiliar words breezed past on the streets, destinations and train announcements booming over the din of tourists and locals returning home for the holidays.

Of course there were the Louvre and the Bridge of Sighs to locate. But there were also mini-markets fronted by Bangladeshi migrants in Florence, North Africans and Vietnamese populating the Parisian districts of Barbès and Ivry-sur-Seine. I was older now, and understood that polemics of power, exploitation, and appropriation remained embedded within these spaces of heterogeneity. Yet they also offered opportunity for encounters and an unplaceable, unspoken sense of understanding.

My mind snapped to times when I clutched the hands of Auntie, wandering through the maze of Burmese shops in Peninsula Plaza, taking in places and scents without a tinge of judgment.

Now, there was something else too—a curl of longing, a sense of having lost and found again.

*

What does it mean now: to pore over the pages of a translated text, to navigate the alleyways of a foreign metropolis? The versions of fiction in the pages between my fingers could well be someone’s picture of reality—somewhere in Yangon, Auntie Moe Moe continues to smear thanaka cream on her cheeks. Perhaps sometimes she hums Chinese pop tunes under her breath, the way I accidentally find myself singing Row, Row, Row Your Boat in Burmese some evenings when my steps feel light on my feet.

*****

Yuen Sin holds a Bachelor of Arts in English and Related Literature from the University of York and is currently completing her MSc in Public Policy and Administration at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She has also written for the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore and the Flying Inkpot, and cares about the role of the arts in community engagement and activism.