Adrian Nathan West (Contributing Editor): German writer Hans Henny Jahnn is one of the least classifiable writers of the twentieth century, and the relative paucity of his work in English translation is perplexing. Among his compatriots, his admirers included Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, Peter Weiss, and Wolfgang Koeppen—the last of whom compared Jahnn’s prose style to Martin Luther’s Bible; Jahnn is one of the poets cited in Roberto Bolaño’s “Unknown University;” and more recently, he was the subject of a long blog post by Dennis Cooper. The philosophical currents underlying his work have much in common with Georges Bataille: the focus on the limit-experience, often attained through an agony that grazes against beatitude, the emphasis on the organic substrate of conscious life, and an unsettling combination of orgiastic excess and monastic quietude characterize both men’s work, though Jahnn’s precise and involuted language is far more innovative than Bataille’s.

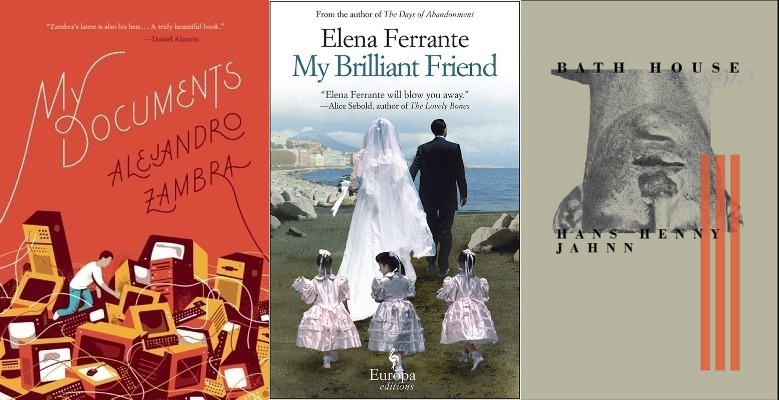

Translations of Jahnn’s work have appeared in dribs and drabs for the past fifty years: The Ship in 1970, Thirteen Uncanny Stories in 1984, The Night of Lead in 1994, and in 2012, The Living are Few and the Dead are Many. All, unfortunately, are excerpts from longer books, so even the most enthusiastic English-speaking reader can have only a very circumscribed idea of Jahnn’s range and brilliance. Most recent to appear in English translation is Bath House, from the unfinished novel Jeden ereilt es, by the small press Solar Luxuriance and translated by Adam Siegel. The book’s as unsettling as Jean Genet, but with an extraordinary animistic power all his own, and these fragments—along with Siegel’s excerpts from Perrduja recently published in Hyperion—should serve as an incitement to someone to finally usher one of Jahnn’s longer works into print.

Another writer I have found recently, thanks to Flowerville, one of the two or three best literary blogs in existence, is the Finnish poet Eeva-Liisa Manner. I bought her poems in French, because it was cheap and I liked the cover, but Waterloo Press has released an English-langugage selection with the lovely title Bright, Dusky, Bright, translated by Emily Jeremiah (for the curious, David McDuff has two magnificent translations of her poems up online). At times dense with speculative rigor and at times tragically desolate, Manner’s sketches of nature lie somewhere between the irredeemable asperity of Celan’s leafless trees and snow hills and the shimmering sea of St.-John Perse.

Finally, I am currently reading Friedrich Schiller’s Essays Aesthetical and Philosophical from an 1884 edition of Schiller’s works I found in a cardboard box in Washington Heights. Though it has undoubtedly been long superseded by more accurate and authoritative translations, there is something admirable about these old versions, rendered long before Wordreference or Wikipedia with elegant, antiquated prose; and these thoughts on the beautiful are among the most inspiring things I’ve read in some time.

Patty Nash (Blog Editor): I let myself go a little in the summer. I’m currently abroad, not-at-home, and when I’m not working on Serious Literary Things I’ve decided to read whatever pleasurable books I please—no “shoulds,” no “rectifying-the-fact-that-you-haven’t-read-X.” So the books I’m into right now are sprints, giddy-up reads, and were I not landlocked I would happily deem them “beach reads.”

Excuse me for being embarrassingly late to the party, but I just read Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend (I know, I know—I report on her buzz practically every week in the Roundup, and really should have read it earlier). I don’t know why I waited so long—typically with books that achieve so much buzz, I feel like I will either a) be disappointed, or b) the buzz itself will have precluded my gaining anything from the actual book (this is a disgustingly snobby presumption, but I have to be honest). Neither thing occurred: My Brilliant Friend simply blew me away. It’s a juicy novel, it’s a novel to make you stay up too late, it’s a complex novel, and it isn’t easy to read—though it certainly is readable. Reading it felt like picking a scab, and I mean that positively: I couldn’t help but pick at it. Though I knew it wasn’t necessarily good for me, it felt good.

Also! I was inspired by Megan McDowell—who was formerly part of Asymptote’s team, hi Megan!—to reading My Documents by Alejandro Zambra (Megan’s the book’s translator!). I actually hope to get a full review on the blog pretty soon, it’s that impressive—just like with Ferrante, I let the literary buzz buzz-and-buzz until I could take no longer, and then got sucked into the mess. Let it be said that this is another book full of stories that are juicy, smart, and slightly annoying.

I lied a bit about the unfettered-fun-reading I took on this summer: I’m also reading Moby Dick (and I’m about halfway through). Hopefully, I will have finished it in time for What We’re Reading in August, so I can (perhaps) deploy a fuller review—not that you need it—but for now I’ll just say it: I kind of get it. It’s a slog, it’s a meditation, but I get it, dude poets, English-language readers everywhere, I get it.

Hannah Berk (English Social Media Manager): Summer’s sprawl makes me crave the epic. I often gravitate toward fragmented narrative, but lately I’ve been caught up in stories that span generations, continents, centuries. Two I’m glued to this month: Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera and Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. These are modern classics, not discoveries. But maybe, like me, you haven’t gotten around to them in the glittering mass of great fiction out there and you need a push in their direction. This is it.

Love in the Time of Cholera is a three-pronged love story that never forms a triangle. Fermina Daza loves then spurns Florentino Ariza. He flits in and out of affairs throughout her long marriage to a down-to-earth doctor, only to reaffirm his passion in old age. The book is unabashedly romantic—that’s one of its pleasures—but it is not unwinkingly so. Florentina Ariza’s lovesickness is a full-on lovedisease; lives and loves are never as sunny as they seem. What’s more, it’s ultimately transporting. Edith Grossman’s translation doesn’t bring García Márquez’s prose into English so much as it creates new English around his prose (and that should be reason enough to read!).

Leaping across continents, but still embedded in the fantastical: The narrator of Midnight’s Children insists on the ineluctable—and often calamitous—entanglement of times and people. Born at the exact moment of India’s independence, Saleem Sinai sees his life as a mirror for the subcontinent itself, along with the lives of all India’s children born within that same hour, with whom he shares a telepathic connection. It’s a pulsing, self-reflexive, and really funny narrative that tackles big questions of memory, colonial legacy, and the metaphysics of pickles. Now’s a really good time to get around to this one since Rushdie’s first novel in six years is due out in September!

Between chapters, I’ve been piecing in Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation and Other Essays. Sontag is a great writer in her own regard, but she’s especially helpful alongside novels of such scope. In the title essay, she argues for a visceral experience of art. In her words: “In place of a hermeneutics of art we need an erotics of art.” It’s a good reminder when taking in literature so clearly embedded in the social and the historical: savor the aesthetic, too. It is summer, after all!

*****