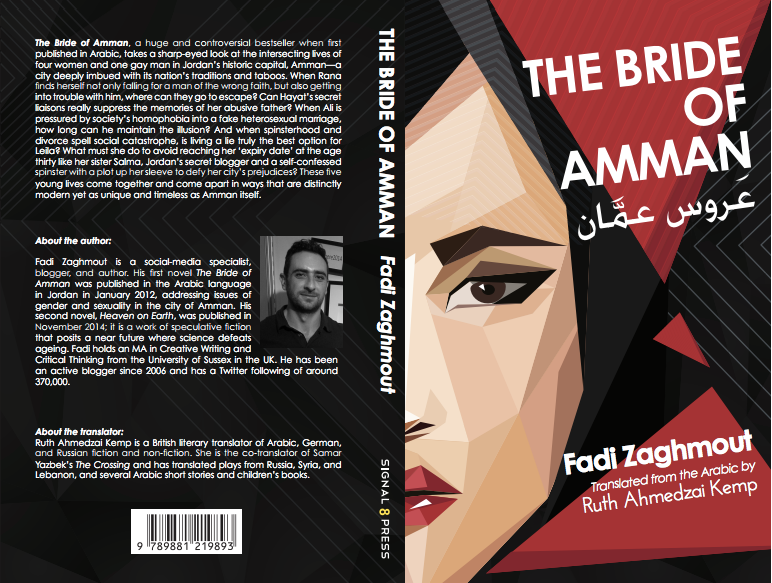

Fadi Zaghmout’s The Bride of Amman (translated into English by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp) is a bold, charged novel detailing the struggle Jordanians face in abiding societal strictures on sexual orientation and gender identity. The taboo topics explored in the novel–including homosexuality, sexual abuse within tight-knit families, sexual harassment in the workplace, extramarital liaisons and interreligious marriage–have rendered the novel quite controversial in the Arab world, with readers either wildly celebrating or denigrating the novel for its “unrealistic” portrayals of Jordanian society.

If we are talking strictly about content, then I belong to the former category. The uninhibited manner in which Zaghmout addresses such realities as living as a homosexual man in a modern, predominantly Muslim community is fresh, engaging, and educational (even for someone who considers herself well-versed in LGBT literature).

It is easy for an author to fall into didactic narration when dealing with such topics. But The Bride of Amman escapes this trap: here is a novel I would encourage both old and young to read simply for its piercing insight into the life of an Arab man—who happens to be both homosexual and a practicing Muslim. This is a story told with such probity that it could be anyone’s.

The novel is structured as a penta-polyphonic narrative, like Alia Mamdouh’s The Loved Ones, and is primarily told from female perspectives complemented by a sole male voice. The primary characters are Leila, an unmarried university graduate crumbling under societal pressures to marry; Salma, her unmarried older sister who secretly pens the Jordanian Spinster blog; Hayat, Leila’s friend who suffers repeated sexual abuse at the hands of her father; Rana, a conservative Christian who falls in love with a Muslim; and Ali, an Iraqi homosexual whose family sought refuge in Jordan after the death of his father.

Zaghmout’s writing style is direct and to the point, not periphrastic as an overwhelming quantity of contemporary Arabic novels are. As a conversation I had with Zaghmout revealed, those who have criticized his work primarily point to his failure to write in a traditional “Arabic” style, replete with adjectives and run-on sentences ad nauseam. Perhaps this “flaw” in Zaghmout’s writing should be celebrated: it endues the novel with a clear-cut quality that reinforces the directness with which he handles his delicate subject matter.

Though The Bride of Amman soars in content and style, it fails to shine structurally. The voices of each character are difficult to distinguish for a good part of the novel, and this shortcoming is apparent in the original Arabic version itself as well. Were each chapter not headed with the name of its main protagonist (aside from Ali’s) it would be an arduous task for the reader to differentiate between the various female voices.

The structural flaws are appreciably redeemed by Zaghmout’s lack of ample focus on the settings framing his novel; names of roads, suburbs and city landmarks are not given prominence in his storytelling. Whether this was a conscious decision or not, it has lent the novel one of its most compelling qualities, which is the ability of the story to belong to any contemporary Muslim society from Morocco to Indonesia. It should therefore not only be hailed as a pan-Arab novel, but as a novel chronicling the trials of individuals struggling to conform to societal diktats in Muslim societies worldwide.

In terms of the translation, I was delighted with the choices that Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp made to keep particular Arabic words in the translated text, as well as her ability to communicate them to the reader without explaining them explicitly. Translators always face the age-old dilemma of either watering down source language references in order to make the end product an “easier read” for the audience, or having an index of keywords or cumbersome footnotes to clarify words left untranslated. Ahmedzai Kemp bypassed this dilemma by deftly guiding the reader by way of context.

As Leila’s grandmother is lamenting Leila’s spinsterhood, for example, she says, “We used to get married young, not like these days … Yallah … God help us, don’t end up like your sister.” Ahmedzai Kemp could have translated yallah into English, but by staying true to the original Arabic she not only endowed the dialogue at hand with a measure of poignant authenticity, but also provides the uninitiated reader with the context to deduce the meaning of the word fluidly, predisposing the audience to a smooth reading experience that enhances the enjoyment of the novel.

While Zaghmout does not aim to provide a panacea for those battling sexual discrimination within Jordanian society—and while The Bride of Amman is in no way quixotic—he aims to simply hold up a mirror to what is truly happening in the shadows in the majority of Muslim societies the world over. It is up to the reader to determine, as they sail through the pages, if they are able to countenance the stark, unexpected reality reflected in the mirror or not.

***

Sawad Hussain is an Arabic teacher, translator and litterateur who holds an MA in Modern Arabic Literature from the School of Oriental and African Studies. She is passionate about all things related to Arab culture, history and literature. Her dream job would be to translate and review Arabic literature full-time.