For a poet, there are easier things than translations. The translating poet inevitably has to face the gnawing burden of writing for two people. “It’s a desperate system of double-entry bookkeeping,” Howard Nemerov lamented. The spectral presence of the author is always hovering somewhere, ready to strike whenever the nuance of a word or phrase falters. Even then, the process of translation is seductive. It provides a poet with the rare opportunity to examine the art of another writer, often with intriguing results. The cryptologist’s glee at unveiling messages and new lines of thought converge into the creation of a new kind of work that is as dependent on the translator’s moment in time as much as it is to the author’s.

Many readers may be familiar with Ciarán Carson’s work as translator. His versions of seminal Irish texts Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) and Cúirt An Mheán Oíche (The Midnight Court) have a robust freshness and vitality that readily appeals to contemporary audiences. Reading Carson’s Táin, one can sense the sounds, smells, and voices of that particular world of pre-Christian Ireland (now so heavily appropriated into the pop-culture fabric of Game of Thrones).

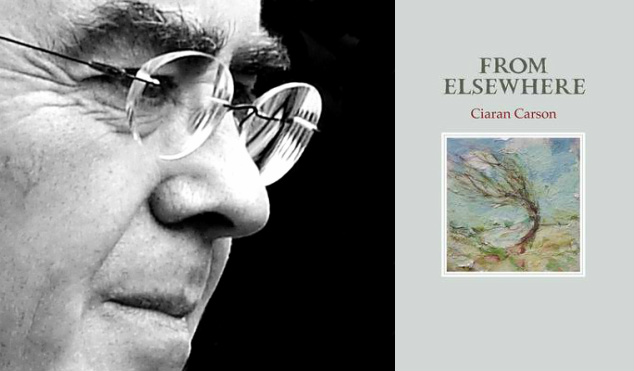

His newest work, From Elsewhere (Gallery Books, 2014), is a collection of 81 short poems by the French poet Jean Follain (1903-1971), each accompanied by a short poem of Carson’s, an original work inspired by the Follain poem, or, as Carson describes it: “a translation of the translation.” From Elsewhere is certainly not Carson’s first foray into French translation. In 1998 he translated an array of Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Mallarmé in The Alexandrine Plan and in 2012 he published his translations of Rimbaud’s Illuminations, In the Light Of (both published by Wake Forest University Press). Carson brings a certain sharp vitality and contemporaneity to his translations compared to those of Oliver Bernard and John Ashbery. He transposes his experience of Belfast, in its own way, a heaving, Gothic, ghostly metropolis, into his vision of nineteenth-century Paris, and his memories of Belfast shattered by the Troubles into Follain’s haunted visions of his native Normandy, scarred by the Second World War.

Carson is a skilled formalist. His poetry collection, Belfast Confetti (Wake Forest University Press, 1989), famously showcased his adroitness with the long line (partly in homage to C.K. Williams). The opening poem of that collection, “Loaf,” involving Carson’s memories of food, heady conversation, and the onus of writing in Belfast in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, is a tour-de-force of expansive energy and rhythm. Even today, in From Elsewhere, we’re shown what Carson can do with concision, which is a great deal indeed.

The Follain poems, supplied with their original French titles (though the poems themselves only appear in the translated English, not in French) are the sounding-board for Carson’s poems, which range from his memories of Belfast during the Troubles to his meditations on light, landscape, and the endurance of art.

The poems take us through haunting periods of Carson’s life, amid sectarian violence in the 1970s. Here with “The Odds”:

A burst of gunfire

in the bookmaker’s shop

where men are smoking

watching the horses

on television

one of them dying

as the pigeons

on the square outside

transform themselves

into a purple cloud boiling up

from the cobblestones

to the sound of their own applause.

to an atmospheric mood piece like “Night Music”:

In the burned-down library

a man manipulates a keyboard

searching for a passage in the cloud

that might shed light

on what he has in mind

the constellations glitter overhead

in roofless space

from time to time

the wind kicks a tin can down the street

a roulette trickle

stops and starts

shouts from the crowd

in a floodlit stadium

greyhounds pursue the grey electric being

that eludes them time

and time again.

The sound of guns, the ashen detritus of bombed buildings, shards of broken glass and discarded bricks and rubbish collude into becoming an unnatural, natural part of daily life. Follain’s memories of his picturesque native Saint-Lô, shelled and destroyed by German and Allied bombing in the Second World War, is a visceral presence in his poems like “L’île brûlée” (“The Burnt Island”), “Le calme” (“The Calm”) and “Police.”

Two of Carson’s later poems in the book, “Night Music” and “The Given Name” which describe the wonder and eerie beauty of a burnt-out library and a derelict bookshop, reminds one of how conflicts can completely tear through the physical and social landscape of a particular place. In the latter poem, a man makes a remarkable discovery from an old book:

he…blows the dust from it

opens it

at a coloured plate

to behold

the emerald bird

that dazzled for a moment

on the threshold of the world

outside his door

One of the most enjoyable features of the Carson’s approach to translating Follain is the way in which he approaches the more conspicuously quiet Follain poems.

Among them are the elegant reflections of the banal, the quotidian, crafted into mysterious rhythms of the strange unknowable beauty of the evanescent world in front of us, as with Follain’s “L’oeuf” (“The Egg”):

The old lady wipes an egg

with her everyday apron

a heavy ivory-colored egg

an irreproachable egg

then looks at autumn

through her little dormer window

it makes a fine sight

framed just like a picture

nothing there

is out of season

and the fragile egg

nestled in her palm

is the only thing

still fresh.

Follain’s “old lady,” his aproned artist, is rendered in the loving gaze of a Vermeer or Chardin portrait, where we share the sitter’s concentration of an object, as she begins to understand something of the otherness of the world.

The only thing missing in this beautiful volume of translations and poetry are the Follain poems in their original French. When W.S. Merwin completed his masterful translations of Follain’s poetry, The Transparence of the World (Copper Canyon Press, 2003), the volume contained the French poem printed alongside Merwin’s translations, enormously helpful to the discerning reader who could share the poet/translator’s discovery.

In From Elsewhere, one feels a bit cut off from that process, as if he’s being blindfolded and led by the hand into a darkened room. Carson’s translations are every bit as vital and robust as Merwin’s, but I would have liked to have seen how he came by them. Take, for instance, a poem like Follain’s “Signes” (“Signs”), which has some of the same stillness and wonder as “L’oeuf”:

Quand un client parfois dans un restaurant sombre

Décortique une amande

une main vient se poser son étroite épaule

il hésite á finir son verre

In Merwin’s translation, we have:

Sometimes when a customer in a shadowy restaurant

is shelling an almond

a hand comes to rest on his narrow shoulder

he hesitates to finish his glass

With Carson:

Sometimes when a customer in a drab restaurant

is shelling an almond

a hand happens to fall on his thin shoulder

he thinks twice about finishing his wine

Strikingly, “sombre” with Merwin is more in line with the literal French, which suggests “shadowy” or “gloomy.” Carson strips the atmosphere in that small café from its illusions and gives us a “drab” place. He also takes a certain liberty by showing us that the lonely customer is drinking a glass of cheap wine, though the Follain poem, which Merwin translates here, simply says “verre” or “glass,” though of course it seems unlikely that this solitary figure would be drinking something else.

Carson has tried quite deliberately (and successfully) to set his translations apart from Merwin’s. Here, as with his translation of the Táin, Carson brings to his work a certain flinty directness that highlights its emotional tensions in unexpected ways.

“When one translates one cannot avoid taking liberties of one kind or another, “ Carson writes in his introduction. “Perhaps one takes a special liberty in translating Follain, whose attachment to his native language was such that he declared himself unable to learn any other.” This is perhaps more than a mere apologia; It is Carson’s way of coming to terms with the inherent difficulties in translating poems and in the great freedom that it can sometimes bring to writers to build upon the work of another.

For admirers of Carson’s poetry, From Elsewhere is a vital new part of his remarkable oeuvre. Belfast Confetti, perhaps his best-loved collection, has been said to remind readers of the scaling rhythms of traditional Irish music, of which Carson is a noted expert. If we were to extend the comparison to music, the poems in From Elsewhere have some of the introspective phrasings of Erik Satie’s piano pieces and are as crisp and concise. The Follain poems and the accompanying poetry by Carson ought to be soaked in by the reader and savored like a good wine, or as Carson has described, “sampled in due course to see if they’re up to the mark.”

It would be remiss and painfully amateur of me to suppose that the Ciarán Carson translations of Jean Follain’s poems and his accompanying original poetry are like savoring two different, but remarkable, vintages of the same fine wine, but what is striking about From Elsewhere is that it allows the discerning reader to glean a sense of what translation does. Thinking in and out of different languages can be potentially inspiring and liberating, something that many Americans (I am often guilty of this myself) forget to do on a daily basis because of the relative global hegemony of English.

From Elsewhere is a rich, intellectually invigorating new addition to Ciarán Carson’s oeuvre. It is one of the best volumes of original poetry and translations to come out in 2014 and it stands apart from many other works for its cleanness, elegance, and cerebral finesse. Carson’s has an uncanny and distinctive ear for sound, rhythm, and cadence, whether it’s for Irish, the coruscating French of Rimbaud, or the sparse melancholy of Follain’s northern French blues. His particular phenomenology of light and dark and his capacity for scholarly adaptation and experimentation is part of what makes Carson such a celebrated poet today. In working off of Follain’s “Pensée d’octobre” (“October Thoughts”), “How good it is/to drink this fine wine/all by oneself/when evening illuminates the coppery hills,” in “Throwback,” Carson creates a story of boys at play, at once wistful and violent, suffused with light, that describes the precarious back-and-forth of the process of translation and the craft of poetry:

Children throwing stones

over the brick wall

topped with broken bottles

ruby amber green

need not know who

drank the wine

all those years ago

nor what lies on the other side

except that it throws back.