Let me talk about selfies.

Are you annoyed yet? I promise this isn’t a curmudgeonly thinkpiece about millennials; nor is it a listicle written by said millennials in defense of the selfie.* No, I’d like to talk about self-portraiture, which became conceivable as soon as mirrors and other reflective surfaces were available. (Narcissus may have enjoyed his reflection in antiquity, but he wasn’t real, and pools of water are never that smooth). The idea here is objectivity. A stable you that you can see.

Even without gadgetry (mirrors, glassy ponds, cameras et al)—I don’t think a selfie is a foray into solipsism. More the opposite: the way the self-it-self has been constructed is a result of the litany of selves surrounding it. We adjust to resemble, even when affirming our individual self-ness. Every selfie (can we say “self-portrait” now? I’m sorry!) exists as an algorithmic product of the selves around it, which, through refraction and contortion, inform whatever “self” is portrait-ed. This is true even sans Instagram.

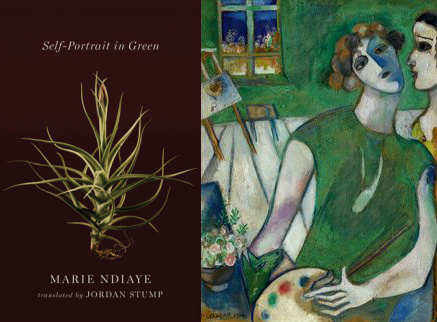

This, at least, is my hypothesis after reading Two Lines Press’ 2014 publication, Self Portrait in Green, by French writer Marie NDiaye and meticulously translated by Jordan Stump. The slender novella is written in the first person against the stark relief of an ominous threat, one of a flood that is slated to destroy the village the narrator inhabits, by 2003. Through a series of recollections, Self Portrait in Green navigates a universe of threat, both environmental and interpersonal, through an interconnected series of engagements the narrator litanies against women afflicted by the color green.

If this novel is a self-portrait, it is a self-portrait of another. Or a series of anothers. A barrage of other women, both defined by the color and donning green if only by metonymy, accompanied with whatever baggage the visceral green imports. A woman in green hangs herself, for example. Another woman in green is the narrator’s best friend—until she marries the narrator’s father. A woman in green hides behind a green tree, or has green eyes. The narrator herself fears she, too, will become a woman in green, through the insidious and downright malicious intersections of self-and-green.

The narrator’s intimate—and sometimes rather skewed, crooked, prickly—encounters with green women are surprising because they are not all alike. I would like to find a theme, a sort of moral platitude with which to explain how the women in green operate against threat of disaster and banality. But there is none. There is only the deep-seated sense of fear, of betrayal, and falsehoods. Many encounters with green women ring false, contrived, mean. Defensive. And others yet are more passive, poisonous episodes of vapidity that prove both artful and full of guile. Green is mistrust, but green is also the narrator, herself. How do we disdain those who make us?

This fictionalized memoir feels elegiac, but not unnecessarily so. It is totally, utterly smart. Self-Portrait in Green is not without humor: though it operates on the same prose-poetic, melancholic, meander-meander style so many of us are familiar with, it is wholly self-aware, and the narrator’s frustrations (at not recognizing a woman in green correctly, or at her own ineptitude at mothering, or her own destiny to become a woman in green) are articulated not only through explicit frustrations but through its linguistic performance (naturally, chapeau to translator Jordan Stump, whose syntax is rhythmically fitting and evocative both in moments of repose and agitation).

Self Portrait in Green reminds us of how thin our vanity truly is. We are porous to the green surrounding us. If only vanity were ours alone to have.