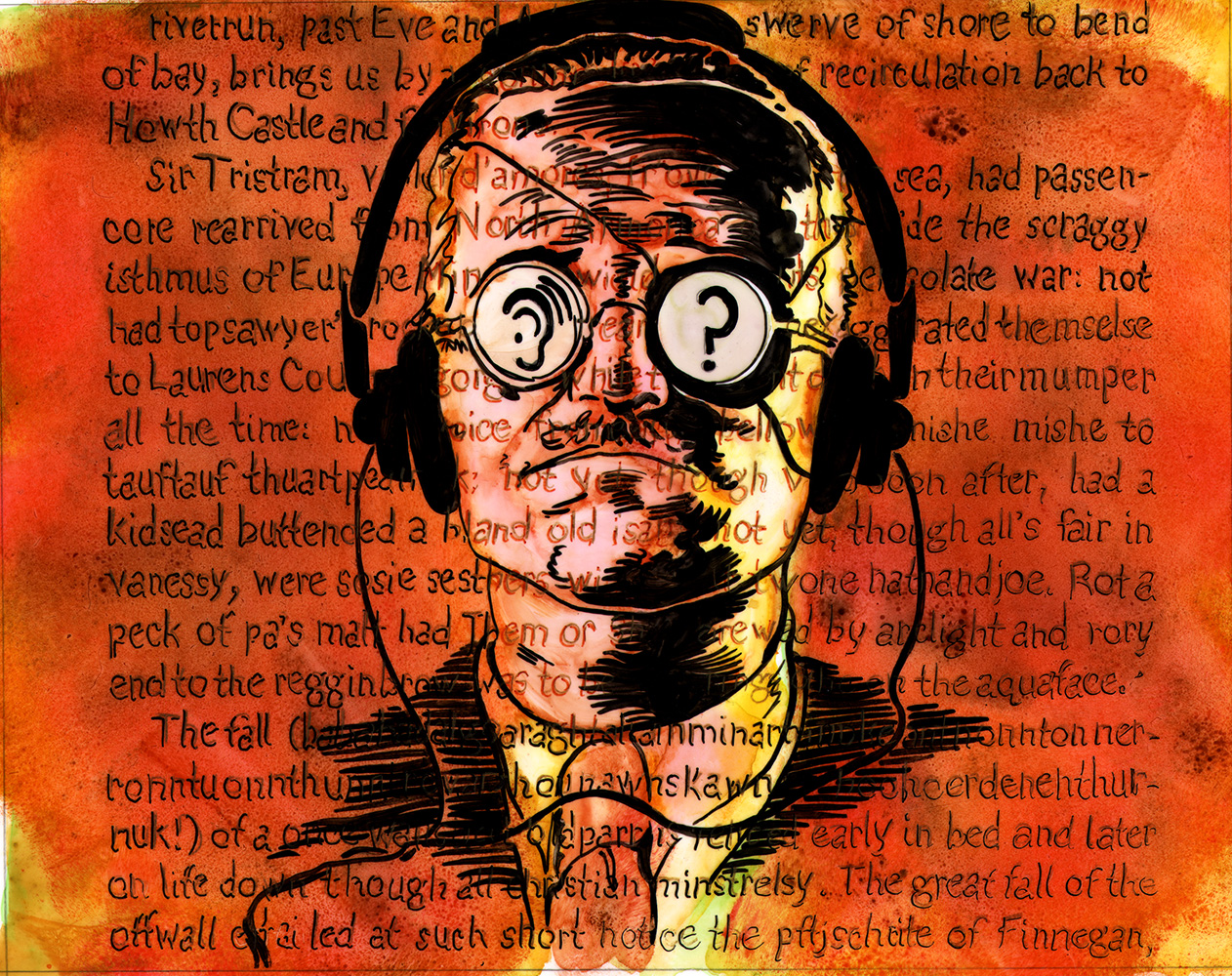

Mariana Lanari hosts performative readings of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake in Amsterdam, and recently recorded two chapters for an audio-musical version of Finnegans Wake, unabridged, called Waywords and Meansigns. Featuring established—as well as up-and-coming—artists from around the world, Waywords and Meansigns strives for a version of Joyce’s work that is stimulating and accessible to even the most casual of readers and listeners. The project officially launched a week ago, on Monday, May 4th: the 76th anniversary of Finnegans Wake.

Finnegans Wake contains over sixty languages. In spite of this, it has, in turn been translated into several other languages from its original English (though a number of translators of the text have given up, gone mad, or mysteriously disappeared, as was the case for a Japanese translator). This raises some interesting questions when considering its “translation” into an audio-musical language. What is lost, gained, or changed when we transfer a multilingual text to a musical, non-linguistic platform? Finnegans Wake reconstructs notions of language, and that process is echoed in converting such a text audio-musically. What we are left with is something resembling a full spectrum of meaning-making (in the loosest sense of the term).

Mariana, alongside composer Sjoerd Leijten, scored the first and last chapters of the text to music. Mariana and I talked about the novel and her involvement in Waywords and Meansigns, including the sensation of foreign-ness, how Finnegans Wake changed her life, and the odd comfort of settling into a vulnerable place of not-knowing or understanding.

Can you say a bit about your process while working on the Waywords and Meansigns project? How did you decide on how you wanted the musical interpretation to take form?

I really wanted to preserve the integrity of the text. Which meant to read every word exactly as it is spoken (in spite of my Brazilian accent). Finnegans Wake is a book that allows for a foreign reader, and a foreign voice. At a certain point I wondered if Derek [the project director] was aware the first chapter would be read in my South American accent?

I don’t really believe in any literal approach to Finnegans Wake. I like the logic of the text, the logic I find in the text. For example, the first few pages of Finnegans Wake present all the themes of the book. And Joyce worked a lot with the Odyssey. In Finnegans Wake, I have the feeling that he used the Odyssey in terms of structure. There’s the subtle beauty of this atomic thing that then explodes in the whole story. And Joyce starts the book with “riverrun” and ends it with “riverrun” as well. So I tried to re-use all the other previews, and everything we did, before we inserted everything. The first page is really full. Encrypted, even. Nobody understands the first page of the text right away. And it’s an interesting thing that it seems the book can only be read if you’ve read it [that first page], somehow. It kind of implies the singularity, and this repetition. So I worked with singularity, repetition, looping, echoing from one part to the other part, and all these words, principles.

Do you think that these different formats make the text more accessible?

The text is never going to be accessible. It’s about changing the approach towards the text. I know a lot about Finnegans Wake because I’ve read and studied it for five years, but everything that I studied brought me to the conclusion that I first had when I read the first four pages of the book. Which is: this anxious pleasure of not understanding something that you should understand. In my case as well—I’d read Ulysses before, and I’d studied Ulysses before—and I can consume English literature a lot, but suddenly you get a book that you cannot understand. To me this is fascinating. What is there—and why, what, how, how do you go on with it?

I’m Brazilian and was educated in a German school, so I always felt foreign, in a way, in my environment. I was sent to Germany in an exchange, and I almost didn’t speak any German then. So I discovered many words in a very severe and strange way that had this kind of stomach-pleasure-anxiety about them. And even today, I live in the Netherlands, and still speaking German—it’s a difficult language. So I find it interesting to inhabit a text where you feel foreign, and you catch twenty or fifty percent of it. You find a way around the not knowing everything.

I really love this tension of being very close to knowledge and not reaching it. It mimics reality in a way. You don’t know the person you’re sleeping next to, you know?

And everyone will have that experience reading Finnegans Wake. No one’s going to read it and understand everything. So it has this universal effect on every reader.

In a way. And I think for native English speakers maybe this is more affronting, because it makes everyone foreign. But if you analyze it linguistically, it deconstructs and reconstructs many words to their origin. His language explodes.

When you begin to notice this it gets addictive. And all the time you find micro-narratives inside the text, which are parts that you do understand. And these parts are somehow enough, through the reading. Plus there’s a kind of conversation that, between the parts you understand and don’t, you create in your head. It’s very inspiring.

What might be at risk in taking that and putting it to music? What did you find could not be carried over – or, was there something that was easier to let go? Do you think there’s some sort of potential betrayal of the text?

In terms of what could not be carried over: it’s the visual text itself I found truly important. It’s difficult when you listen because a lot of words are written so they sound like something that’s not exactly what they say. This is something you see written, but sounds imbue another meaning.

That said, I guess the best parts of the recording are when we indeed are able to translate the text into musing, sentence by sentence, as in linguistic translation. Or when music is composed to a specific passage. We see this version we present now as a first approach that raised the desire of diving deeper into each passage, working carefully on oral aspects of the text and composing a musical dialog with it.

Are there any specific passages or phrases in the text that posed a particular challenge for you?

Many of them are challenging. But the biggest challenge was the part I’d read most, because it’s the part I like the best: the last part of the book, the soliloquy, with Ana Livia. It’s the last nine pages of the book. I did the whole recording and I said, “Fuck, I’m going to have to record this again!” because it was so bad. Because I know it so well, somehow a mixture of my emotions that have to do with the story. I agonized a lot over this story. And I over-interpreted it, I crossed it with my own emotional experience. So this was, paradoxically—the part that I know more—the most difficult to record. I guess I didn’t separate myself from that part. I went through what that woman went through, in my personal experience. We were listening to it yesterday and I was like, “What did I do?!” It was so dramatic, I hated it.

Do you think there are other opportunities for learning about Finnegans Wake in the audio version than there might be from simply reading it?

Well, for those who are doing it, certainly. In any translation, for whomever is reading it for the audio, you get this background of the text, you see the words from behind somehow. For the listener, it depends. There’s this thing they say about Finnegans Wake: it gives back to you what you give it. So if you open the book for five minutes and never read it, you might find it either fun or violent or this or that. The person must want to read it and have the desire to get through the text. It’s not easily digested for anyone, not even the audio version.

But with the audio version you can then enjoy it in another way. It’s supposed to be enjoyed in all those other dimensions. Finnegans Wake is approached as a book, but it doesn’t really fit into literature, it is a much broader work of art. When you try to make it fit into the rules of literature, you get annoyed.I like this kind of reaction. It says a lot.

It’s controversial, which is usually a good thing.

Yeah, people are uncomfortable with not understanding things, as if they understood everything!

It’s so important to be put in that position of discomfort.

Yeah. And I find comfort in that.

It’s a sort of vulnerability to not understand something…

Yeah, and imagine putting yourself in that vulnerability. But it’s a vulnerability that we experience so much. Yeah, why would you want to read something that you don’t understand? That’s a good question, of course.

Last summer I did a small presentation at the yearly workshop in Zurich, when the theme was walking and wandering. It was very valuable to me to read the book only searching for passages with walking and it’s variations. For my surprise there is hardly a page where coming or going in doesn’t appear. Even letters and words and the nose of the reader walk through the pages of the book. Well, that left a strong image to me and I projected it in what I expected from the recording. I wanted to create this idea of a character that moves through the text, that walks, that sleeps, that slips. Sjoerd makes soundtracks for video games and movies as well, so I had this fantasy in my mind. Then the process of doing it was us going through a passage, making an image of it, then I would read and Sjoerd would create the sound.

Reading Finnegans Wake is like arriving at a conversation in the middle, we don’t understand at the beginning, but if we continue listening, we eventually get into it. It’s like being in a different place not knowing what is happening, at the same time that we are producing this place ourselves, in the act of reading, which makes it strangely familiar.

*****

Mariana Lanari hosts performative readings of Finnegans Wake at RongWrong gallery in Amsterdam. In 2014, she did a contact improv reading in 4 voices for random audience, at Gallery ZSenne, in Brussels. She is working on a Model of an Analogical Dictionary based on the Wake. Mariana is doing her master’s studies at Sandberg Instituut/Gerrit Rietveld Academy, in Amsterdam, and is part of School of Missing Studies.

Rebecca Hanssens-Reed is a writer and translator whose work can be found in The Saint Ann’s Review, Treehouse Magazine, Dressing Room Poetry Journal, and elsewhere. Her translation of Margarita Mateo Palmer’s novel, Desde los blancos manicomios, is forthcoming from Cubanabooks Press. She works at an organic bakery and lives with her houseplants in Northampton, MA.