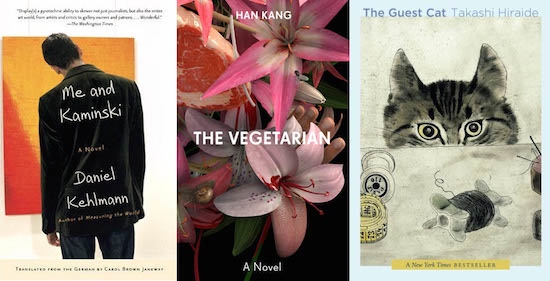

Ellen Jones (criticism editor): Three of the best things I’ve read this month have been slim, 100-odd-page volumes in translation. The first is Takashi Hiraide’s The Guest Cat, translated from Japanese by Eric Selland. The book was recommended by a great lover of cats who insisted I read it in hard copy rather than on my Kindle for the hypnotisingly green feline eyes on the book’s jacket. My family has always had cats, a number of them so embarrassingly rotund—despite years of controlled diets—that we’ve had to wonder whether a well-meaning neighbour wasn’t regularly spoiling them with choice titbits from the table or bowlfuls of cream. So I found much to relate to in this quiet story of a young couple’s relationship with a local cat, whose daily visits revitalise their marriage and ignite an enthusiasm for gardening. Hiraide’s writing (he is primarily a poet) had rarely been translated before, but The Guest Cat has become a bestseller in the United States, France, and now Britain; the ubiquity and inexhaustible popularity of cat photos and videos on social media speak volumes about this book’s potential appeal. But there is so much more to it than a plot summary might suggest—it meditates on the transience of life and beauty, and masterfully maps out a domestic space with the precision of an architect. This is undoubtedly a book for cat people and dog people alike.

The second is Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, translated from Korean by Deborah Smith (you can listen to Daniel Hahn talking about Deborah’s translation on our podcast). Depicting a world in which the decision not to eat meat constitutes a bold act of rebellion against male authority, this novel illuminates South Korea’s alarmingly strict attitudes toward women, marriage, and family. Prompted by recurring dreams of violent bloodshed, Yeong-hye is driven to vegetarianism, veganism, and finally to anorexia. Physically repulsed by meat and meat-eaters, she is sexually attracted only to a man painted from head to toe in bright flowers, desiring, at the novel’s close, to become a plant herself. Portobello Books’ jacket sublimely reflects the novel’s capacity to surprise its reader: the fresh pink blooms with their red pistons hide at first glance a slab of meat, a livid tongue, fat black flies, and even a red-veined eyeball. Full of startling colours, and featuring scenes both disturbing and erotic, The Vegetarian is the most powerful novel I have read this year.

Finally, I want to mention Yuri Herrera’s Signs Preceding the End of the World, translated from Spanish by Lisa Dillman. Adorned with praise from some of the brightest lights in Mexican and Latino fiction, this novel is translated into an English so estranged and creative that it made me want to read every sentence twice. As Makina journeys north across the U.S.-Mexico border to look for her missing brother, we hear what can be learned by moving between languages, between ‘native tongue,’ ‘latin tongue,’ and ‘anglo tongue’: “if you say Give me fire when they say Give me a light, what is not to be learned about fire, light and the act of giving? It’s not another way of saying things: these are new things.” The novel’s appearance in English is itself a fresh reflection on the productive nature of language mixing and translation.

Mui Poopoksakul (editor-at-large, Thailand): I have three reading buckets at the moment: my running list of books I’ve been meaning to read for ages; books translated from German (I’m newly living in Germany and learning the language); and the many, many Thai books I picked up at the book fair in Bangkok last fall.

From the first bucket: I finally got to Paul Auster’s The Invention of Solitude and wish I had read it a lot sooner. The tension and interplay that Auster sets up between fragmentation and the unconscious fight for narrativity, for the “rhyme in the world,” are immensely powerful. I found myself at the Musée Picasso Paris while I was reading the book, and it struck me that The Invention of Solitude had a cubist appeal to it. In the first part of the book, in which his father’s death prompts Auster to write about the man, the author says, “At times I have the feeling that I am writing about three or four different men, each one distinct, each one a contradiction of all the others. Fragments. Or the anecdote as a form of knowledge.” Then, throughout the second part of the book, Auster intersperses recurring meditations—on chance, memory, his son, Pinocchio, and the Biblical Jonah, among other things—told in short segments, and their tangled form becomes illuminated by the end.

From the German pile: I was given Me and Kaminsky, Daniel Kehlmann’s novel, translated by Carol Brown Janeway, about a would-be biographer who noses his way into the life of his subject, an aging renowned painter. While the book is said not to be Kehlmann’s best (perhaps because of its moments of heavy-handedness), it was a fun—and very quick—little read that was enough of a gateway book for me to want to read more by the author.

Finally, on the Thai front, I’ve been “buffet reading” bits of many different books in an effort to sample different authors. Unfortunately, pretty much nothing of what I’ve been reading is available in English, but I’ll mention one standout I keep returning to. Duanwad Pimwana, a highly regarded contemporary female writer, has a body of work that resolutely depicts human resilience, and a number of her stories portray an array of female characters whose problems are not about trying to have it all, but about trying to bear it all. I’d love to translate her.