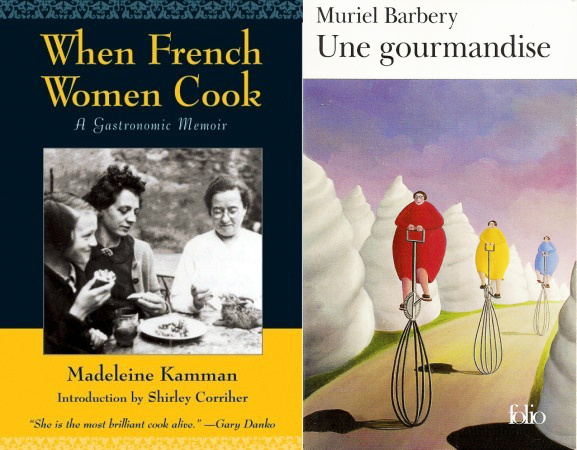

I have never been able to cook from Madeline Kamman’s When French Women Cook. I read the recipes and my mouth waters: noisettes de porc au pruneaux from Claire in Touraine and tarte à l’orange from Magaly in Provence. Yet I cannot convince myself to cook them. The lists of ingredients appear too systematic for food that has more to do with familiarity and wisdom than measurement.

The herbs in my fridge have spent too long away from the earth, the red ocean perch far too many hours out-of-water. The stage is wrong: a railroad apartment in West Harlem with dusty windowsills and dreamed-of copper pots could never measure up to a grandmother’s worn-in kitchen. I dream of meeting these women, listening to them, absorbing their habits and tricks. More than their food, I want their knowledge.

Kamman tells the stories of eight different women in different regions of France. They all cook, some more professionally than others. All are wise and rooted. This collection of stories and recipes archive an approach to living that is rapidly disappearing. Kamman memorializes this disappearing way of life through documenting a history of French cooking, insisting that women are the masters of the kitchen.

She writes the history of women’s spaces and women’s work. They may have been domestic, but they were powerful. A passage in Muriel Barbery’s Une Gourmandise also points to power held by women in the kitchen. A food critic and a group of apprentices eat lunch at a fancy restaurant. Dessert arrives—a scoop of orange sorbet—and one of the apprentices says it reminds him of his grandmother. He continues:

“‘I think [our grandmothers] were aware, without saying it outright, that they accomplished a noble task in which they could excel and which only appeared subaltern, material or basely utilitarian. They knew, beyond all the humiliations suffered, not in their name but by reason of their condition as women, that once the men came back and sat down, their reign as women began. And it wasn’t about control over ‘the economy of the interior’ where, sovereign, they would take revenge on the power men had at “the exterior.” Far beyond that, they knew the feats they realized went straight to the hearts and bodies of men. …They held their men not by the strings of domestic administration, children, respectability or even the bed—but by their taste buds…No chef cooks, has ever cooked, like our grandmothers. All the factors discussed here produced a kind of cooking so specific, that of housewives, enclosed in their private interiors: a cooking that, sometimes, lacks refinement, that always has that ‘familial’ side, that’s to say consistent and nourishing, made to ‘stick to your ribs’ – but which is, at heart and most of all, of a torrid sensuality, from where we understand that when we talk about “flesh,” it is no accident if that evokes the pleasures of the mouth and of love conjointly. Their cooking, it was their charm, their appeal, their seduction.’”

Like this critic’s grandmother, the women Kamman writes about cooked from their bodies rather than from books. Their recipes reflect their surrounds and their histories: a profound sense of regional food distinguishes each woman and her kitchen. Many of her recipes, she is sure to note, have never been written down before. The recipes she documents have grown out of the labor of women, out of their gardens, town markets and larders. For these women, food is their labor and sustenance.

Cooking that is lived, rather than taught; shared, rather than documented. There is no obsession over nutrition or origins: there is just the food as it flows from seasoned memory and deep roots. It is these I find misbalanced in trying to cook from the book. The food loses something essential in the journey from their bodies to my kitchen counter. It isn’t so much a question of frustration at not being able to replicate as frustration with distance. These recipes are so much of a place that I fear their dislocation.

*****

Nina Sparling is a recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College, where she studied food politics and comparative literature. Currently she works as a cheesemonger in Brooklyn and interns for New Vessel Press. Her blog, The Analog Kitchen, hopes to offer a kind of cooking that responds to place and memory as much as to proportion.