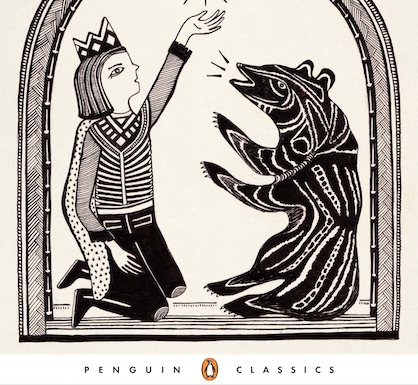

The following is an interview with translator Maria Tatar, of Franz Xaver Von Schönwerth’s The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Tales, available here—and if you’d like a taste, check out our recent Translation Tuesday, featuring the short story “The Enchanted Fiddle!”

Could you talk about the Turnip Princess and what sort of fairy tales they are?

Schönwerth collected his stories from farmhands, domestic servants, artisans —people who worked for a living and were experts in the art of gossip, improvisation, talk, and storytelling. His official work took him into royal quarters, but he was deeply committed to capturing tales told by adults in workrooms and around the hearth. Unlike the Grimms, who were equal-opportunity collectors, begging and borrowing from all social classes, Schönwerth wanted tales untainted by literary influences—hence the rough-hewn quality of many of his stories. He did not smooth out rough edges, add psychological motivation, or make stylistic “improvements.” The Turnip Princess lets us listen in to storytelling sessions from times past. And suddenly, once you’ve read a a dozen or so of these tales, you begin to see how they were put together and animated for audiences.

How did you prepare to translate this sort of writing?

I suppose I could say that I have been preparing for this work all my life. I was trilingual for a brief period as a child, speaking Hungarian, German, and English—never confusing them according to my parents, and thank goodness for that. My graduate work in German Studies took a literary turn, and I did not begin research on folklore and fairy tales in earnest until I started reading fairy tales to my children in the 1980s. Translating the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen for my annotated editions of their work was in some ways actually not the best training ground for Schönwerth. The Grimms and Andersen strive for a carefully constructed folksy tone; Schönwerth by contrast just puts on the page what he hears. I often had to resist the temptation to smooth out the rough edges and create a reader-friendly story.

What do you hope English-language readers gain from reading these tales? Who’s your ideal reader?

There’s nothing like this collection in English. My hope is that readers will begin to see how fairy tales are part of an oral tradition deeply connected to print culture but also different from it. These stories take up all the traditional tropes—iron shoes worn out in a search for the beloved, an ogre mother-in-law who kills her grandchildren, and glass mountains that require scaling—and then put them in new combinations that create mashups not unlike what we see today in something like Into the Woods.

How do you negotiate other mythic analogues in relation to those in the Turnip Princess? Did you look to specific translations or writings for inspiration to create your own vernacular in the stories?

I loved reading Philip Pullman’s translations of the Brothers Grimm, as well as Angela Carter’s rendition of fairy tales written down in 1697 by Charles Perrault. Both stay faithful to the letter and the spirit of the originals. I tried hard to rethink each sentence in English. How would an English speaker have said that? I wanted the German syntax to vanish into thin air.

What is the place of the fairy tale in contemporary literature?

Folklore is foundational when it comes to literature. Before people were reading books and watching films, what were they doing? Telling stories. Sometimes it was the same old story, but often it took new twists and turns, shape-shifting as it adapted to a new social environment to become culturally relevant. Those stories are still with us today—we are constantly hitting the refresh button on “Little Red Riding Hood” or “Cinderella,” making them new. At the same time the tropes of folklore have migrated into print culture and new media, and they flash out at us in unexpected ways—a lost shoe in “Sex and the City,” a reference to fairy tales and necrophilia in “Mad Men,” or the Flying Africans in Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon.”

What are you reading/writing right now? (alternately: what’s your favorite book of late?)

Right now I’m working on African American folktales, discovering a vast folkloric network that draws on African, European, and as well as other sources as it also creates its own unique vernacular. Tainted by slavery and often told in dialect (a brilliant adaptive mechanism that backfired in the twentieth century and came to signal lack of “education”), these stories were also appropriated by writers like Joel Chandler Harris, who turned them into stories for a white “little boy.” I am working with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., to reclaim that heritage and show how powerfully it operated in the antebellum and post-bellum era.

How did you come in contact with this project?

Erika Eichenseer explored the municipal archives in Regensburg and found these fairy tales stored away in 30 boxes containing Schönwerth’s posthumous papers. She transcribed the stories and published some in Germany under the title Prince Dung Beetle. She approached me about translating the tales. I read them and presto! signed on.

How did you overcome the implicit cultural assumptions (I assume) are to be found in each text?

I had the good fortune of being able to call Erika Eichenseer whenever there was a particularly challenging passage. Not all translators have that luxury. The real test for me had less to do with the cultural assumptions underlying the tales (I’ve spent the last twenty years studying German fairy tales) than the lack of logic in tales that were orally transmitted. When you tell a story, there are always gaps and bumps in the narrative road. No one is sitting at a desk, reviewing, revising, and making sure that every word is in the right place. I had to channel my inner folklorist on many occasions, reminding myself that skillful raconteurs are deeply invested in holding the attention of his listeners. They don’t mind loose ends, lack of logic, and missing links as long as the story ticks and whirrs.