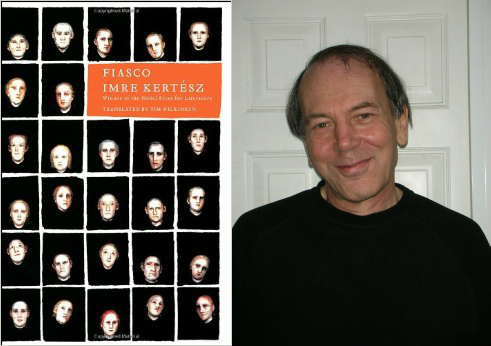

Tim Wilkinson (b. 1947) grew up in Sheffield, S. Yorks., but has lived most his adult life in London. He is the primary English translator of Hungarian writer Imre Kertész (titles including Fatelessness, Fiasco, Kaddish for an Unborn Child, Liquidation, Detective Story, The Pathseeker and Dossier K) and, more recently, Miklós Szentkuthy (Marginalia on Casanova, Towards the One and Only Metaphor), among others, as well as shorter works by a wide range of other contemporary Hungarian-language authors. Fatelessness was awarded the PEN Club/Book of the Month Translation Prize for 2005.

Q: How did you learn your foreign language, and how did you begin working as a literary translator?

A: I learned Hungarian “on the hoof,” mainly by moving to Budapest around Easter 1970 and marrying the girl with whom I had by then fallen in love, having made several trips there since 1964. I might add that I sort of picked up German in much the same way (minus the love complications), by taking up a job in Switzerland, 20 years later. Contact with speakers of a language is, for me, the important feature, just as it is with small children… The strictly “literary” translation work only really came about ten years ago, after I had been translating a fairly wide range of non-fiction (mostly with a pronounced historical flavor) as an add-on to my main job (which was in an altogether different field and had little or nothing to do with translation).

Q: Who is your favorite fictional character of all time?

A: Probably Tristram Shandy—if not Beckett’s Murphy or, rather later, Elias Canetti’s Kien (Auto-da-Fé); perhaps Franz Biberkopf from Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz.

Q: Who was your first favorite writer and how old were you when you discovered them?

A: As far as I can remember (back to the early fifties), it was Elleston Trevor, purely on account of Ant’s Castle, but I can’t remember the name sticking for too long; by my teens I had already got started on Charles Dickens and the like.

Q: What is your favorite word in any language? Which word do you find most difficult to translate?

A: Legato (or maybe ‘spool’).

Q: What 5 books would you want with you if you were stranded on a desert island?

A: Tristram Shandy and at least one of Beckett’s works, to I would probably add Imre Kertész’s Kudarc (Fiasco, as it was published in English) along with a couple of other living Hungarian writers (e,g. Gábor Németh) who only exist in English largely thanks to Asymptote’s attentions. Last summer, Iván Sándor’s Legacy was brought out in the United Kingdom by Peter Owen; it had been previously released in German translation in 2009 under the title Spurensuche (‘Searching for Traces’).

But then, I didn’t mention Kaddish for an Unborn Child, which is what actually set me off in the direction of literary translation in 1996.

Q: Do you have a translation philosophy that guides your work?

A: Just look for (and find) the most accurate possible way of representing what the author has written in an appropriate tone. It’s not a philosophy as such but quite close to what translators into Hungarian or German aspire to: do one’s best not to obtrude, or “Get out of the way!”

Q: Which of the translations that you’ve worked on was the most challenging? Why?

A: I suppose the Szentkuthy ones, not least because he was writing on a formidable range of subjects, from what most people think of as fairly abstruse mathematical theory, physics, botany, music, literary theory, painting, and so on.

Q: Which one author do you think most deserves wider recognition worldwide?

A: I could easily add a couple of dozen other living Hungarian authors, but let me content myself with just mentioning György Spiró.

***