There is a way a room full of people drinking cocktails feels. It is distinct from the stale fog that spills from a fridge packed with six packs, and it is altogether different from the rosy-cheeked stupor induced by a case of wine. There is a severe and attentive atmosphere to the room. The alchemy of balancing sweetness, bitterness, and bite in a few ounces is mysterious and tempting. There is a self-awareness that comes with drinking an old fashioned, an edge to the precarious glass that a Manhattan arrives in. There is also enormous satisfaction in drinking a good one. The pleasure doesn’t last long—the drinks are always short and expensive.

There is also the fine distinction between the cocktail bar, the cocktail party, and the party where there are cocktails. The first two belong to a class with deep pockets and shined shoes, but the third is a strange intersection of refinement and grit. Rather than opening a can of beer or uncorking wine (the more democratic beverages), there is a dance of mixing and shaking and ice: cocktails are designed to impress. At the “party where there are cocktails,” someone always mixes drinks. This is the difficulty: the cocktail depends on the bartender. It is much more difficult to help oneself. The beverage is meant to be served, creating the attentive, severe atmosphere.

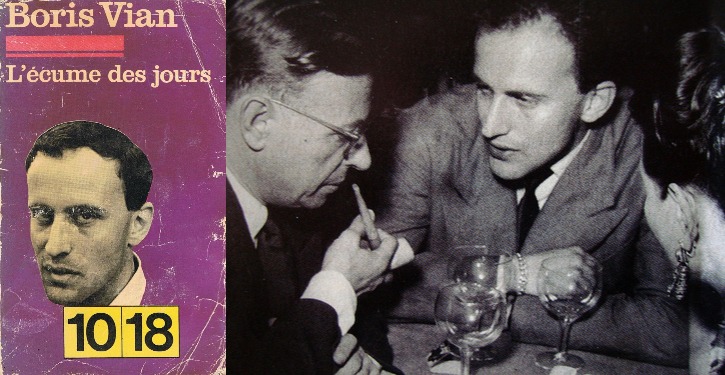

How to temper that stiffness, I wonder? In Boris Vian’s L’ecume des jours, Colin has perfected his dream machine: a pianocktail. He is a lovesick engineer, ever-toying with reality. The machine composes cocktails based on whatever the associated piano is playing. Here, he introduces it to his quirky friend, Chick.

“Would you like an aperitif?” asked Colin. “My pianocktail is working, you could try it.”

“It works?” asked Chick.

“Perfectly. I had trouble getting it working order, but the result is better than I had hoped for. From Black and Tan Fantasy, I got a truly stunning blend.”

“What’s your formula?” asked Chick.

“For each note,” said Colin, “I have a corresponding alcohol, a liquor or an aromatic. The strong pedal corresponds to a beaten egg and the soft pedal to ice. For seltzer water, there must be a trill in the highest register. The quantities follow the logic of length: the sixteenth note equals a sixteenth of the unit, a quarter note the entire unit, a whole note four times the unit. When they play a slower tune, a system of calibration is put into place, such that the amount will not be augmented—which would make for a too abundant cocktail—but the alcohol content. And, following the tune, one can, if desired, change the value of the unit, reducing it, for example, by a fifth, to be able to have a drink that takes into account all the harmonies by way of a lateral adjustment.

“It’s complicated,” said Chick.

“The whole thing is directed by electrical contacts and relays. I’m not giving you the details, you know that. And anyway, to boot, the piano really works.”

“It’s marvelous!” said Chick.

“There is only one troublesome thing,” said Colin, “It’s the strong pedal for a beaten egg. I had to include a special system of engagement, because as soon as we play a piece that is too hot, bits of omelet fall into the cocktail, and that’s tough to swallow. I’ll modify that. Right now, it’s enough to pay attention. For crème fraîche, it’s G flat.

“I’m going to make myself one from Loveless Love,” said Chick. “It will be terrific.”

The idea is charming, down to the detail of the problem of the beaten egg. Vian’s pianocktail is a delightful imagined device, and indicative of the ways he uses the obscure or fantastical to comment on our own absurdities as people, on our own absurd interactions. His pianocktail makes a subtle mockery of the staid room of drinkers. He gives over the exactitude of mixing drinks to musical variation. What was heady and poised becomes loose and improvised. The frenetic energy of getting it right is extinguished with his machine. Music fills the room with dancing bodies and corresponding drinks. The pleasure of alcohol is freed from convention and service. Drinking is playful and the “party where there are cocktails” becomes the party with music, dancing, and conversation.

****

Nina Sparling is a recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College where she studied food politics and comparative literature. Currently she works as a cheesemonger in Brooklyn and interns for New Vessel Press. Her blog, The Analog Kitchen, hopes to offer a kind of cooking that responds to place and memory as much as to proportion.

Read more: