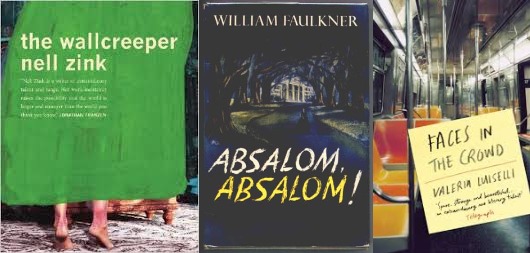

Tiffany Tsao (Editor-at-large, Indonesia): Family sagas make up my month’s leisure reading so far. Jeffrey Eugenides’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning Middlesex and William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! have been on my to-read list for several years, and it was with a combination of sheepishness and triumph that I finally got round to cracking open their spines. One occupational hazard of being a literary academic is that you often lack the energy to graze beyond your particular fields of expertise. As a recent post-academic, it has been a great pleasure indeed to read more in the way of the American “classics”—and not just so I can finally stop embarrassing myself at dinner parties where I often disappoint fellow guests by not having read every work in the western canon, all the latest prize-winners, and everything listed on the latest “Top 100 great reads” list circulating the web.

As far as sagas go, the two books couldn’t be more different. Middlesex is a record of metamorphosis. Our protagonist and narrator, Cal, discovers at the age of fourteen that she is also a “he”—to all appearances a female, and raised accordingly until puberty hits and she discovers that she is, chromosomally speaking, a man. But other transformations abound as well: a brother and sister fleeing Greece turn themselves into complete strangers, then lovers, then newly-weds; a bootlegging grand-uncle resurrects himself from the dead as the charismatic leader of a black Islamic cult; urban decay hollows out the once vigorous heart of Detroit. Middlesex sings of change; Absalom, Absalom! of the immutable: Thomas Sutpen at sixty as he was a young man, possessed throughout by the same monstrous yet innocent (or perhaps monstrous because innocent) ambition; Judith Sutpen, face frozen in calm impenetrability (those same words throughout: “calm,” “impenetrable”) from young fiancéedom to elderly spinsterhood; Miss Rosa Coldfield in moral and emotional developmental suspension—“a crucified child.”

If Eugenides’s book is a joyful and humorous paean to life’s motion, its dynamism, then Faulkner’s novel is an elegy on all levels—those whose stories it tells through Quentin’s conversation with Shreve, all dead, and even their lives recounted as a sort of living death; Quentin himself dead (we know this from the earlier published The Sound and the Fury); the post-war American South they populate, also, in essence, dead.

Middlesex being my first Eugenides, I came to it not knowing what to expect in terms of style and tone, so its energy caught me off guard. It’s a narratorial voice always on the move, one minute giving us the gods’ eye view from Mount Olympus, the next floating in pre-existence awaiting its birth; one moment in Berlin with 41-year-old Cal shyly looking for romance, the next with Cal’s grandparents several decades prior as they consummate their marriage. For the most part, the tale of Cal’s family and of Cal herself follows a linear chronology; but these continual interjections and perspectival shifts remind us that between past, present, and future, between historical record and imagination—just as there is between sexes—there is wiggle room, and that wiggling is not only fun, but restorative. Given Middlesex’s joyfulness, the shock was all the greater when I plunged into Absalom, Absalom!, even though I knew full well what I was getting into (it’s my third Faulkner, and as always with Faulkner, a cognitive and sensory immersion). I am still reading, passing now through the final third of the book. And the telling of it is the dreaming of the same nightmare again and again, but each successive time in finer detail, in greater vividness, in incrementally increasing melancholic horror. A bleak note on which to end the calendar year, perhaps. But there is a cocoonish comfort as well to be found nestled in the folds of Faulkner.

Patty Nash (blog editor): I am a graduate student surrounded by people who are more well-read and smarter than me (or is it “I”?). In another world, for another Patty, this might bode badly. But I’ve been reading quite a bit lately, and loving—or finding redeeming qualities in—mostly all of it. (Sometimes, it’s hard to know what to enjoy anymore: is that a problem for anyone else? I am so voracious my appetite is hardly whettable. Ergo: the two reviews that follow hail from the reading I’ve done in the past two days.)

Today (actually, by the time the post goes up, it will have been tomorrow) I started and finished Faces in the Crowd by Mexican writer/Asymptote blog contributor/activist-by-way-of-introduction writer Valeria Luiselli. I also reviewed Luiselli’s fantastic essay collection, Sidewalks, also from Coffee House Press (and totally flipped over it). I have an unfortunate proclivity to expect disappointment after initial success, so the fact that I loved reading this slim, bright, perceptive novel is testament to its quality.

Faces in the Crowd might be categorized as what many critics are (annoyingly) dubbing the “new fiction.” It’s certainly refreshing, and exciting to read, but it isn’t reinventing the wheel—it’s honed the wheel, making an exact science out of every word. (For this, I clearly have translator Christina MacSweeney to thank, who also translated Sidewalks.) The book allegedly echoes Luiselli’s own time spent as a translator of little-known books in Harlem, following a fictional poet, Gilberto Owen, inserted in Garcia Lorca’s New York among a multitude of other artists, both real and imagined. The book is serious, but doesn’t take itself, or its heavy subject matter, too seriously. It is slender, poetic, and bright. It is fun to read and blithely reflective: perhaps it owes more to the prose poem than to the epic historical tome its subject matter could otherwise invite, and I can’t quite explain a “prose poem.” But I read it in a day, and that should be enough endorsement.

I also just finished (yesterday—or, correction: the day before!) The Wallcreeper by Nell Zink. Set in Berne, Switzerland, it’s another annoying example of what I’ve read other bloggers dub “new fiction.” I am starting to suspect that this “new fiction” is really just “well-written fiction,” which isn’t necessarily new—just hard to come by. I loved, loved, loved The Wallcreeper for its light absurdity and strange logic, for its spareness. If I were to write fiction, I should hope that my description rang as sincerely and as lucidly as the often-bizarre, always-surprising, consistently genuine descriptions in Nell Zink’s prose.

The Wallcreeper isn’t translated, but there’s a sense of translation, of nation and environment that I just can’t shake. The protagonists are not at home, ever, in the book, and that sense of unease distills and swells violently throughout this (exceedingly short) little book. The novel is written from the perspective of a character named Tiff (no relation to the column or the aforementioned editor-at-large), who is newly married to Stephen, a dedicated birder. The two struggle with predictable domestic issues: miscarriage, affairs, communication, blah blah. But there’s a serious edge to this book, a sharp and almost mean sense of nihilism that is both shocking and shockingly satisfying (N.B.: I also read this in a single sitting).

Read more: