I am often asked what life is like in Russia and I struggle to provide a judicious answer. Americans, I think, want to understand what to expect from a shifting Russian state. The formative years of the wheelers and dealers of modern-day Russia were experienced under the psychological weight of Khrushchev, Brezhnev, and Gorbachev, and if someone wishes to understand Russia, she would do well to study the complexities of the Soviet baby boomers. To answer our new question, “What was life like in the Soviet Union?” I can now answer with:

Read Word for Word.

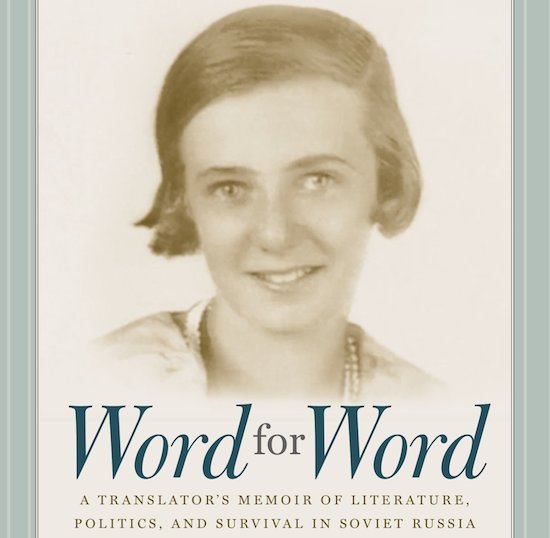

It is not often someone buys you a book and refuses to speak with you until you read it, but this happened to me with Word for Word, out now in translation from Overlook Press. The title is an adulteration of the original title podstrochnik, a so-called “trot” or bare literal translation of a text that a translator processes into a work of art. Written as an extended interview and based on the documentary film of the same name by Oleg Dorman, Word for Word is the memoir of Lilianna Lungina, perhaps the most successful translator of the Soviet Union.

Though born in 1920 in Smolensk, Russia, Lungina, spent a privileged childhood in France, Palestine, and Germany. Her father, who passed on to her the German language he had picked up in a prisoner-of-war camp, shortsightedly returned to his homeland of Russia from Paris, and in 1933, Lungina followed. Landing in Moscow, Lungina saw herself as a Jewish bourgeois “French Mademoiselle” of the twenties who barely spoke Russian (at the time, the teenage Lungina read Russian only from the postcards her father had mailed to Paris). The shock of leaving the liberal modernism of 1920s Paris for the state-controlled Stalinism of 1930s Moscow was one from which she could not recover.

The language barrier alone engendered difficulties at school until she transferred to a German-language gymnasium from which she was “tipped” to drop out before the faculty and students were accused of collusion with the enemy. A German speaker with a German-speaking father, Lungina was a natural target of the 1930s purges (no matter that her father had been a prisoner of war.) Still, she dropped out in time to escape persecution. This was but one of many strokes of luck that kept Lungina out of the labor camps and prisons. Tragically, however, many of her days were spent witnessing friends and relatives disappear.

At the start of the Soviet entrance to World War II, Lungina was sent by steamboat to the tiny Tatar city of Naberezhnye Chelny, where she worked as a newspaper reporter and learned to saddle and ride a horse to collect statistics from villagers. “If a Parisian Jewish girl can ride and saddle a village horse,” she said, “Then anybody is capable of anything.” When she returned with undesirable statistics, Lilianna was told she must invent them so as to keep up appearances for the powers that be.

After the war, she returned to the city to try and find work. Struggling against Jewish quotas in Soviet universities (as a rare native speaker of French, her matriculation should have been a shoo-in), Lungina found she still had a strong command of German. Nonetheless, she was unable to find work at the Russian State Publishing House into the 1960s. One day, lamenting that her natural dream of becoming a French translator could never be achieved, a friend suggested she try and study Swedish literature. She had never seen any Swedish text, but made a great discovery upon opening a book. With its similarity to German, Swedish was comprehensible to her. She studied up with haste, having found an untapped market. She dragged a sack of books home and parsed through the Soviet library’s social-realist schlock until she came across the work of Astrid Lindgren. Lungina was unaware of the world-wide renown Lindgren already enjoyed outside of the USSR at that time, but fell in love with Pippi Longstocking. The fruits of this chance meeting were translations that became the classic bedtime books of so many Soviet children, and spawned incredibly popular animated cartoons (Lindgren’s Karlsson-on-the-Roof is more well known than Pippi Longstocking in the former Soviet Union). Success cast Lungina into the intelligentsia of Moscow. After Karlsson-on-the-Roof’s publication, publishers began to close their eyes to the “Jewish factor.”

While most translators of Russian life are émigrés to the West, Lungina’s take is unique because she became a Soviet citizen late in the game. Lungina was well into middle age before she saw success and was allowed to translate intellectual authors such as Strindberg and Hamsun, as well as French writers. This late blooming is an inspiration to those who feel they are lagging behind their contemporaries, especially as Lungina watched popular contemporaries fall out of favor and into camps. She rubbed shoulders with some of the great Russian writers of the time (Akhmatova, Solzhenitsyn, Shalamov), and her memoir treats these experiences with the eye of an objective observer. Her often funny caricatures of beatified writers like Solzhenitsyn (who comically instructs posh party guests which vegetables not to eat in order to save their souls) bring a humanity and realness to books that formerly seemed beyond criticism.

Personal stories like these are equated with the great ones, giving the book a social complexity rarely seen in analysis of any nation. Lilianna tells an anecdote, for example, of getting a call in the middle of the night from a friend saying, “You have to read this!” and witnessing the subsequent battle to publish One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the seminal publication of the Khrushchev thaw if not all of Soviet history—and it is given the same clout as a personal disagreement with some teachers who were picking on Lungina’s son at school.

By the 1960s, Lungina had met her husband and lifelong companion Semyon Lungin, a screenwriter who penned such classics as the excellent summer camp romp Welcome! Or: No Trespassing and Georgian director Otar Ioseliani’s masterpiece There Once Lived a Song Thrush. Up through perestroika, Semyon and Lilianna saw their friends marked for publications, sent to labor camps, exiled, and murdered. Toward the end of the film version, the audience watches Lilianna hold back tears, talking about a time, shortly before Semyon’s death, when he insisted to go out for bread with her. “Come on, let me come with you!” he pleaded. “It’s just more fun that way.” After hearing all the harrowing tales of their married life and menaced acquaintances, the viewer, too, is touched. Semyon surrounded her with a “cloud of love” despite their “penniless desperation.” The scene is as moving as any gulag memoir this Russian lit major has been forced to read. Lungina credits her life’s pressures with deepening their love, and implies that a family without stress might not have such strong emotional ties as her own.

As the Soviet Union approached its end, Semyon and Lilianna came to know the full extent of the KGB in their lives, and became embittered toward the brittleness of the late-Soviet system. One tale recounts a train ride to Kiev to see off their friend Viktor Nekrasov, who had been exiled from the USSR. In their compartment, the Lungins met a stranger who broke out the cognac in order to celebrate Nekrasov’s departure. The stranger then revealed that he knew their itinerary because he was in fact the KGB agent shadowing them, and proceeded to rehash their own thick dossiers.

In Lilianna Lungina’s memoir, we see a Soviet Union filled with people, not characters, a conglomeration of nations whose citizens were sent on fantastic and dangerous adventures and bickered over petty fights with the PTA. The long scope of these lives, with their highs and lows, produces a strange mixture of hope and cynicism absent from much American writing. An unusual sort of resignation to fate that many Soviet citizens underwent is well described and justified here.

The psychological effects of this political system set the stage for the many “stranger than fiction” anecdotes of Word for Word. While Welcome! Or: No Trespassing written by Semyon Lungin was given the green light, a film about turtles was prohibited because the censors took it as a metaphor for the Prague spring. The reasoning was, apparently, that the turtles represented Czechoslovakia because the words in Russian begin with the same letter.

The eight-hour film version of Word for Word was shelved for 11 years before being broadcast on Russian state television. It is not entirely clear to whom a blunt description of the past could be seen as a threat, but when the film was finally released in 2009, it was met with wide acclaim and director Oleg Dorman received the prestigious TEFI prize. Dorman refused the award, saying that the same powers who presented it to him had also prevented the film from being shown.

The story does not end there. The publication of Word for Word in book form brought not only more details from the original interview, but was a surprise success. The original printing of 4,000 copies instantly sold out, and bigger and larger printings and sales ran into the hundreds of thousands. Something about the book struck a chord with audiences.

I think the fact that summer camp even existed in the Soviet Union might surprise some Western audiences, let alone that the Soviet censors approved an anti-establishment parody of it. Lungina’s keen memory and keepsakes are enough, but her portraits of KGB agents, the literati, and pre-revolutionary Russian souls amount to relics of an entire society. These are real lives of human beings, not sob stories of the defeated. The conspicuous absence of unrelenting negativity is an asset. Wisdom and intelligence suffuse Lungina’s descriptions of her triumphs and disappointments, and make for fine reading. Lilianna Lungina discovered Russia for herself, and then became an important part of it. Word for Word is not only a tool for understanding the past, but as a well-rounded view of life in the 20th century, it is also a key to understanding the identity of those who call themselves Russian in the 21st.

***

Harry Leeds is a translator of Russian poetry, a prose writer of food and culture (Lucky Peach, The Journal, Roads and Kingdoms, Black Warrior Review), and a general lover of things unreasonably priced and far away. He has an MFA from the University Florida. You can find more about him at his website. Tweets @mumbermag.

Disclaimer: The views and information presented in this article are the author’s own and do not represent those of any other individual, organization, state, or institution. The direct quotations from this article are the author’s own from loose notes and are different from those you will find in the translation by Overlook Press.

Read more: