It was January in New York and exceptionally cold. I took refuge in the kitchen and picked the complicated recipes, the ones that would prove that I could, that I had the patience and humility to follow the details of the book. I pulled the Roberta’s Cookbook off the shelf. Roberta’s opened in Bushwick, Brooklyn, in the winter of 2008. The restaurant is a couple hundred feet from the Morgan Avenue stop off the L train, one of the vital organs of the neighborhood. Industrial buildings turned post-grad housing with complicated zoning laws line the streets. From outside the restaurant it looks like a bunker. The cookbook was new to the collection, a gift I had given my mother. It lay horizontal atop my parents’ mass of weathered, yellowing, greasy cookbooks.

The cookbook has high-design photographs of food and blurry low-res pictures of PBR-fueled parties side by side. The narrative between recipes is crass and anti-corporate. The restaurant and its clients have found emancipation from domesticity, freedom from the boredom of home. The food shows an attention to detail and creativity. There are nods to simplicity with a dose of the unexpected: a plate of blistered padrón peppers with savory lemon curd and fennel pollen. The plate comes to the table still smoking. The peppers appear to vibrate in the noise: loud people and loud music. Pizza arrives, seared in the eight-hundred-degree wood-fired oven by the front door. The food resonates in the space: it’s delicious, it’s quick, and it’s informal.

In those pages, eating dinner is a performance.

Looking through the cookbook in my parents’ kitchen that winter, this felt okay. My home felt wobbly and with this kind of cooking I could triumph over faltering traditions. It was a sneaky no thanks to improvisation and the enduring art of home cooking. Cooking from it required well-stocked grocery stores and arrogance. I sought out 00 flour for pasta and introduced myself to fiore sardo, a smoky, wooly sheep’s milk cheese from Sardinia. The recipes were inconvenient and boasted their innovation and imagination, begging for acknowledgment and praise. I brought dishes to the table, awaiting satisfaction. I had followed the book. I had succeeded in the art of reproduction.

But I still felt like little had been accomplished. There was no story behind the food; it could have been made anywhere, for anyone. This kind of food travels well in print but lacks soul. It is from a kitchen, not a home. There is no dirt under fingernails or grit accumulated on weathered pots; the pages are ill equipped for absorbing grease.

I found discrete challenges to these attempts to transform the intimacy of the kitchen into a space of reproduction and exactitude in unexpected books and poems. This passage from Colette’s Prisons et Paradis illuminates a vocabulary that produces a very different kind of eating. Food is tied to place, is connected to the earth that ingredients are taken from. I find in her vocabulary an antidote to cuisine, a morsel of warmth.

Is it a recipe? No. A primitive culinary preparation, old as an olive tree, as angling for fish. Never has a way of cooking demanded less fuss—it requires nothing but the proper approach.

Have only… a Provençal forest, at least southern. Supply yourself with select wood: horned trunks of olive trees, sticks of sunrose, roots and branches of laurel, pine needles weeping golden resin, the tiny brush of Terebinth trees, almond wood, do not forget the shoots of grapevines. In the ground, between four big pieces of granite, build, light the fire. While it burns, red, white, cherry, licks of gold and blue, there is nothing to do but watch it. Above it, the green sky of Provençal twilight turns lake-blue.

The flames lower, quiet down; you have in your hand one if not several beautiful pieces of Mediterranean fish, right? All cleaned? In Saint-Tropez you got a giant scorpion fish with the face of a dragon, or you brought clever black-backed mullets from Toulon, and you did not forget, while cleaning either this one or that one, to slip, along their empty bellies, a sheath of lard? Good. Ready your broom, as I call the perfumed bouquet of laurel, mint, savory, thyme, rosemary, sage, that you had tied up before lighting your fire. Ready then the broom, soak it in a pot filled with the best olive oil mixed with wine vinegar—here we only allow vinegars pink and sweet. Garlic—you thought naively we could skip it?—crushed, just to the consistency of cream, improve the mixture as necessary. Salt, a little, pepper, enough.

Colette writes about the experience of eating in a place, of experiencing a place through cooking. Her tone is cynical and authentic. She taunts the reader too rooted in her own traditions to give herself over to the sensory, and sensual, possibilities of the hearth. Her poisson au coup de pied, or kicked fish, bathes in the herbs and oils of the Mediterranean. Earlier on, she mocks the tourist who “demands his steak with apples, cooked medium rare, his eggs with bacon, his spinach and his ‘special’ coffee.” While the poisson bathes in olive oil, garlic, and a bouquet of herbs, the tourist only “roasts himself.” Cooking here is not about aptitude or expertise but about instinct and attention. Il n’y faut que la manière—all you need is the right attitude, the proper approach.

***

Nina Sparling is a recent graduate of Sarah Lawrence College where she studied food politics and comparative literature. Currently she works as a cheesemonger in Brooklyn and interns for New Vessel Press. Her blog, The Analog Kitchen, hopes to offer a kind of cooking that responds to place and memory as much as to proportion.

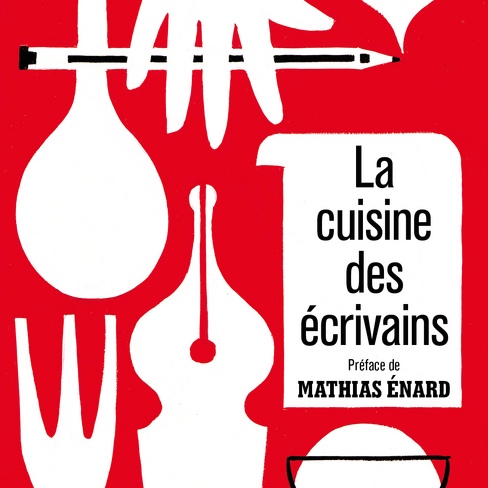

Excerpt from the collection La cuisine des écrivains. Paris: 10/18 Editions Inculte, 2010.