It was a full house at the New York Public Library on Wednesday night, and I learned just how similar Iranians and Israelis are.

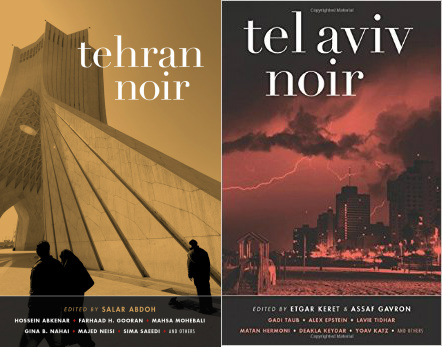

Rick Moody moderated a panel event for Live at NYPL, launching two new books from Akashic’s Noir Series: Tel Aviv Noir and Tehran Noir. Akashic Books’ Noir series includes over sixty anthologies of noir stories set in cities around the world. The panel guests included Tel Aviv Noir editors Assaf Gavron and Etgar Keret, Tehran Noir editor Salar Abdoh and Tehran Noir contributor Gina Nahai. Sitting in the audience, listening intently, I felt complicit.

I had translated eleven out of the fourteen stories in Tel Aviv Noir (two others were written originally in English, a third was translated from Spanish). I felt that where the book succeeded or failed, I shared some of the responsibility. I also felt simultaneously in and out of place: I’ve lived in Tel Aviv most of my life, but have never been to Tehran, though when I see pictures of its mountains I get that belly ache of longing.

These two facts are connected: as an Israeli Jew, much of that world is closed to me.

From political factors on both sides pointing accusatory fingers at the danger that lurks in the enemy country (a helpful tactic when a political distraction is required); to a viral campaign in which people on both sides posted their pictures online, holding signs that read “Iranians/Israelis, we love you, we will never bomb your country,” the similarities between the two countries showed themselves in surprising ways.

Moody had clearly read both books carefully, as well as his guests’ other writing, and other books from Akashic. One question came up over and over again: what is noir about these cities? Israel and Iran both bring to mind war, but Tel Aviv and Tehran are identified as cultural hubs, party cities, cosmopolitan tourist attractions. What has noir got to do with these cities? Moody insisted.

Imaginations and recollections began to flow. Keret pointed out that basically everyone in Tel Aviv, even the gentlest soul, knows how to shoot a gun. Many, he added, have military training that goes beyond the shooting range. They could break a door down with their foot. Abdoh spoke about the raging methamphetamine problem in Tehran. Gavron talked about the underrepresented populations of Tel Aviv: the prostitutes, the crime families, the migrant workers, the African refugees. Nahai said that the parties in Tehran were illegal and held in underground locations. In Tel Aviv riding a bus is a gamble that might cost you your life. In Tehran censorship brings down most every attempt to write creatively. Both cities are filled with people of different ethnicities and backgrounds, people seen by many around the world as symbols for the conflicts in which their governments are involved, but people who, nevertheless, fight their own battles and deal with their own hardships, while the shadow of politics mars everything they do.

Perhaps most poignant was the definition of noir offered by Abdoh: a sure thing gone wrong. This description seems so perfect for the situations in both Israel and Iran in the past twenty or thirty years. Shattered dreams, lost faith, a narrative we’ve worked so hard to sustain, and that nevertheless crumbled before our eyes: our countries gone astray, Tel Aviv and Tehran providing small consolations, bubbles in which to pretend that things have gone as they should have.

Nearing the end of the event, an argument was sparked between the two Tehran Noir representatives. While Nahai claimed that things in Iran have gone from bad to worse and that they would only continue to deteriorate, Abdoh insisted that there was hope: not everything the Islamic Republic was doing was bad, life was marginally better now, and might become better still.

“Is he covering his ass?” the person next to me whispered. I don’t think so. I think Abdoh truly sees, or wants desperately to see, how things might still work out. Nahai vehemently disagreed, stating that there was no real way of living in Iran today. In a moment more personal than she might have wanted, she said, “You don’t know, you don’t live there.” I later find out that neither Abdoh nor Nahai live in Iran full time, although obviously both are very much involved and preoccupied with its past, present and future.

This argument between them resonated so much with me that it brought tears to my eyes. I’m an Israeli who lives abroad, and as such, I am constantly questioning myself and being questioned by others on what I can and cannot say. Last summer I happened to be back in Tel Aviv on a visit during the most recent war. My presence there, in the bomb shelters, in front of the news, on the angry and anxious streets, gave me some leeway in the eyes of others as to the validity of my opinion. This was a fluke. I could have just as easily been shut down, the way Abdoh was. Had I stayed while my friend moved away, I might have been making the same understandable argument Nahai was making.

Until we can find peace, we will forever be hurting and away from home, no matter where in the world we are. As I listened to this eerily familiar disagreement, I yearned for the version of Tel Aviv that steers clear of Noir: the bars, the beach, the shorts. The sense of being able, if momentarily, to forget that there is an entire country around me, embedded in reality, in upheaval. I wonder if the speakers on stage felt the same.

*****

Yardenne Greenspan, Asymptote editor-at-large for Israel, has an MFA in Fiction and Translation from Columbia University. In 2011, she received the American Literary Translators’ Association Fellowship. Her translation of Some Day, by Shemi Zarhin, was chosen for World Literature Today’s 2013 list of notable translations. Yardenne’s translations include work by Rana Werbin, Gon Ben Ari, Nahum Werbin, Vered Schnabel, Kobi Ovadia, Yirmi Pinkus, Ron Dahan, Alex Epstein and Yaakov Shabtai. Her fiction, essays and translations have been published in Hot Metal Bridge, Two Lines, Words Without Borders, Necessary Fiction, Agave, World Literature Today, Shelf Unbound and Asymptote, among other publications. She is currently working on her first novel.