From October 1st to the 8th, the Mexican Cultural Institute of New York paid tribute to the centennial of Octavio Paz’s birth with a series of discussions, readings, concerts, and film screenings. A prolific poet, essayist, intellectual, translator, editor, publisher, and diplomat, Paz published his first poetry collection, Luna Silvestre (Wild Moon, 1933) at 19 years old, penning over 26 volumes of poetry until his death in 1998. Paz was also an accomplished essayist: his 1950 treatise on Mexican identity, El laberinto de la soledad (The Labyrinth of Solitude) is considered a seminal work of literature. The recipient of the Cervantes award in 1981, the American Neustadt Prize in 1982, and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1990, Paz founded three literary magazines, Taller, Plural, and Vuelta; Vuelta is still published as Letras Libres.

Now that we’ve gotten that dry but necessary introduction out of the way, let me truly begin.

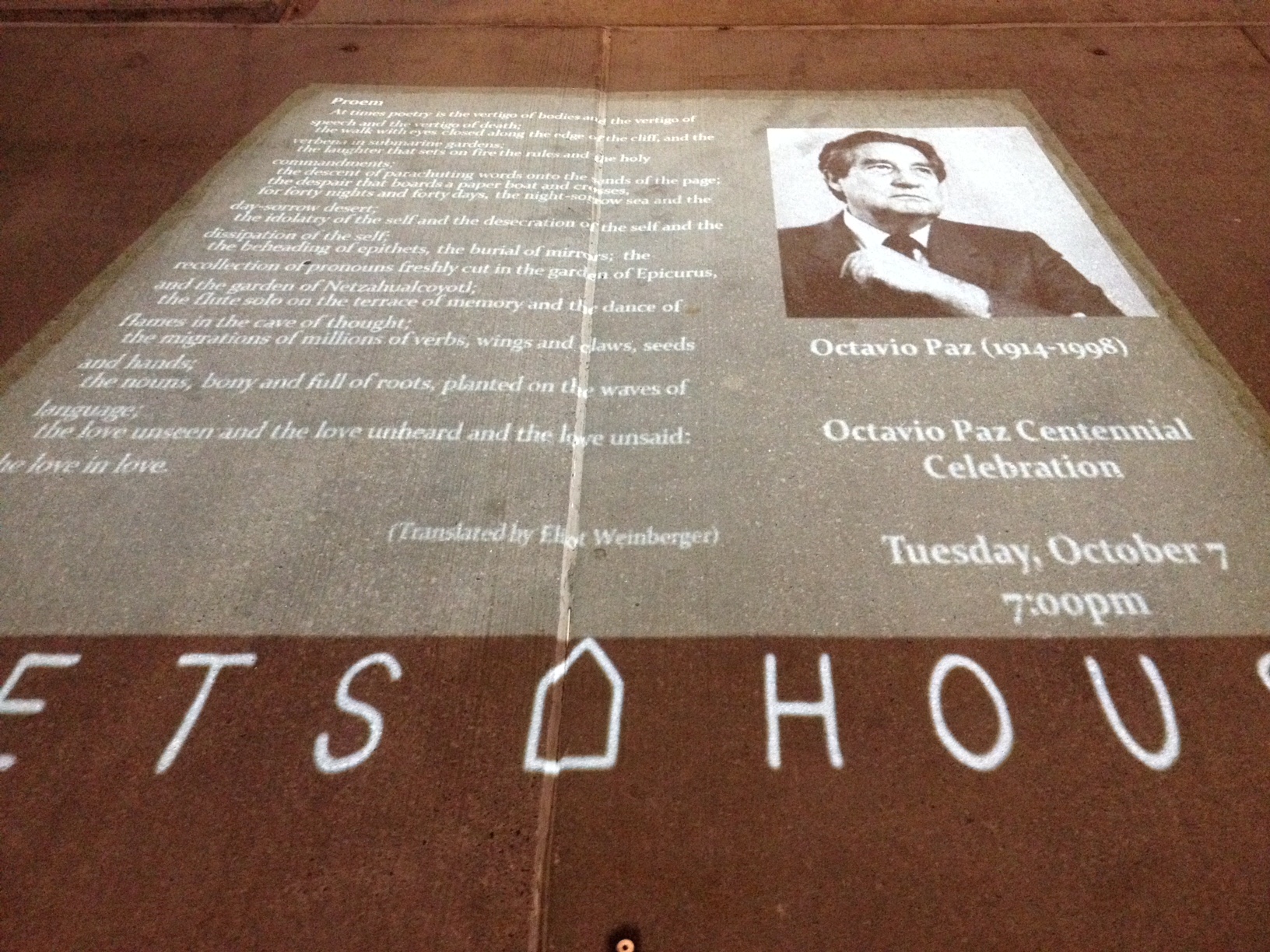

The centennial celebration was a sumptuous banquet I wanted to gorge myself on until I developed gout, like those rich men of old. I eagerly chased Paz throughout New York City, from the second-floor gallery of the Mexican Consulate in Midtown to the ornate ballroom of the Americas Society in the Upper East Side, and finally to where the river meets the city, the “navel of the poetic universe,” as Paz’s translator Eliot Weinberger playfully referred to the Poets House in TriBeCa.

I confess to have been enamored of Paz since discovering his work at seventeen—and at seventeen, aren’t we all torn-jeaned, Converse-clad Columbuses, naming plants and rocks and rivers that have already been baptized, thinking we discovered a new world? It was in this same way I felt I had “discovered” Paz, had read and felt and understood him in a way no one else could. I was not surprised to learn then that nearly everyone involved in the centennial felt similarly, and had been energized and influenced by the startling force that is Paz’s poetry.

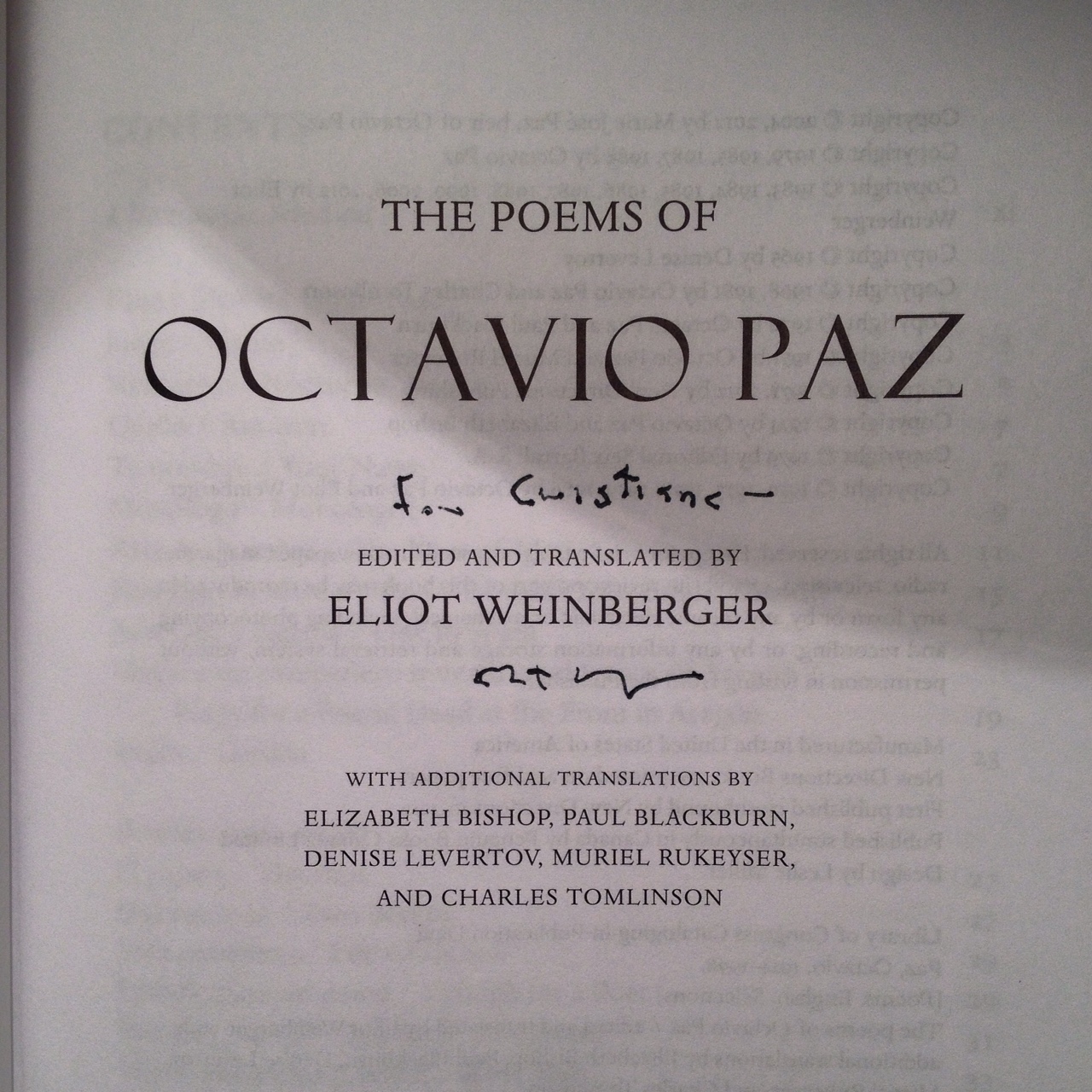

During the intimate discussion on October 6th between Eliot Weinberger and Mexican poets Maria Barranda and Coral Bracho, Barranda recalled how as teenagers she and her friends would read “Sunstone” after school and cry. Also at seventeen, Weinberger began reading and translating Paz as a means of learning how to write poetry; his discovery led to a decades-long love affair wherein he became the primary translator of Paz’s poetic oeuvre.

Though no longer seventeen, the three panelists were as enthusiastic as teenagers. The room at the Americas Society was beautiful and genteel, outfitted as thoughtfully as a Victorian debutante, and there Weinberger lay the scene for clips of a documentary on Paz from famed ethnographic filmmaker, student, and close friend of Paz, Robert Gardner.

The casual vignettes consisted of Paz and his wife Marie Jo guiding Gardner around Mexico City, introducing the director to central characters in Paz’s works like the Paseo de la Reforma, el Zócalo, and San Ildefonso, the school Paz attended. The poet is fascinating to watch as he narrates the history behind the architectural and communal spaces to the camera: blue-eyed and impish, he is full of awareness, his infectious curiosity written on the lines of his face. His knowledge of Mexico City is “encyclopedic…[he had] an amazing memory, total recall,” Weinberger confides. In one scene, Paz explains that he enjoys visiting churches not to worship, but rather to see their constructions, the “delirious forms.” If, as Paz claimed, religious experience has aesthetic value, isn’t the opposite true as well? Isn’t art—this room, this film, this discussion, this poetry—its own revelatory, faith-inducing experience?

A shot of Paz sitting at his dining room table reading “Nocturno de San Ildelfonso” was delightful—the camera’s tight and askew focus captured a handsome, graying author, at ease with himself. Weinberger paused the film to read his translation of the poem, and it was like listening to a fairy tale you once knew but forgot the details of: the plot is the same, but the tone, the lyricism, the turns of language are quicker, made anew. It was a lovely translation, and I thought of Paz’s belief that “translation is a process indistinguishable from poetic creation,” (“Introduction,” Renga). Paz translated over 600 pages of poetry, from William Carlos Williams to Fernando Pessoa to Baccio to Sanskrit, and understood intimately the process of translation.

Weinberger revealed that, for Paz, the translation of his work was a way for Paz to read himself. On a few occasions after reading Weinberger’s translations, Paz would see things he didn’t like, certain words or images, and would change these in the original manuscript. For me, being there was like having the good, dumb luck of standing in the right place—perhaps next to the bar—at an excellent party and overhearing fascinating, intimate gossip about the host.

Politically, Paz was essentially a European socialist, an anti-communist who was perceived as right-wing but was, by American standards, “quite the left-winger,” Weinberger explained. While young, Paz advocated “revolution,” but came to the realization that at different instances, revolution can limit the manner in which art is created and experienced, and he was against anything that limited expression. To Bracho, Paz was a “needed presence” in Mexico.

The discussion then turned again to “Sunstone.” Weinberger spoke of how, in the 1940s, Paz was in New York dubbing Mexican films, living at Columbia University. His girlfriend lived on Christopher Street, the scene of a melodramatic four a.m. fight that prompted Paz to flee and return to his apartment uptown. Paz hailed a taxi with a bent axle, which made a da da da da da da da sound throughout the entire ride, inspiring the “trance-inducing” rhythm of “Sunstone.”

“It is probably the only major work inspired by a New York taxi,” Weinberger chuckled, and I could tell this was one of his favorite anecdotes, as he repeated it at both events, sincerely amused each time. The trance-like spell stayed with me, and I mimicked the hurried pattern while walking home, dubbing my own New York-set heartbreak over Paz’s. It was soothing, like falling asleep on a train with your head against the wide windows, your thoughts becoming plane with the passing horizon.

It is this, then, that attracts so many to Paz: complex concepts striking at the door of lyrically sensuous imagery, something akin to math behind melody. Paz’s work is so deftly composed that his intimacy becomes our own and is our own search for self, for humanity, for meaning. His poetry is a contemplation of politics, history, tradition, which inevitably circles back to Paz himself.

The next day, October 7th, the Poets House hosted a selected reading of Paz’s poetry by seven poets and Weinberger. The reading was in a small, cozy, white room, filled to the brim. To me, even before the reading, the question of translation was ever present: that night, there was Paz’s original poem, the translated poem, the recited poem, and the poem each audience member internalized. There were several interpretations happening at once, a current of creative spark occurring before our eyes, for each poet lent a different power and agency to the work they chose to read. Poetry was being written with each recitation—“the poet creates images, poems; and the poem transforms the reader into an image, into poetry… Poetry is nothing but time, a perpetually creating rhythm,” (Paz, The Bow and the Lyre).

Kristin Prevallet’s reading of “Sunstone” was forceful, unstoppable, as if she had to bring the words to surface from somewhere deep inside her all at once. Maria Barranda read “Paisaje” and “Temporal” in Spanish, and her voice was lilting, sure, almost pleading; her emotion was palpable and transferable, her voice kindling a warmth of recognition and enjoyment in my own chest. Idra Novey mentioned how even now, upon learning of the recently discovered student mass graves in Mexico, she was reminded of Paz’s politics and beliefs (Paz left his ambassador post in 1968 in protest over the Mexican government’s handling of student protests).

Her interpretations of “Duration” and “Interior” were hurried, juxtaposing the reflective, serene imagery and tone of the pieces. Roberto Tejada framed his reading of the prose poem “El mono gramático” in an unorthodox and utterly spellbinding manner. He wove sections of the original poem in Spanish with Helen Lane’s English translation, and it was so seamless that it took me several words to notice he had switched between languages. Monica de la Torre, before launching into her charmingly lispy reading of “I Speak of the City,” called Paz a “gateway poet.” Coral Bracho’s readings of “Como quien oye llover,” “Figuraciones multiples,” and “Niño y trompo,” was delicate and almost trembling, like a sparrow’s wings fluttering against themselves. She recounted how upon meeting Paz for the first time before one of his readings, she mentioned her fondness for “Como quien,” to which Paz replied he was sorry, but that poem had not made it to that night’s reading. He then walked out and opened with “Como quien.”

Fittingly, Weinberger read the closing poem, and his choice was a sentimental one: “Response and Reconciliation,” a dialogue with Francisco Quevedo and the last poem Paz wrote. To Weinberger, this was one of Paz’s best poems, something he considers unusual, for late-life works are not most artists’ best. Weinberger’s voice was like a BBC documentary narrator’s, measured and deep, conscious of the ceremony he was conducting:

“Man and the galaxy return to silence.

Does it matter? Yes – but it doesn’t matter:

we know that silence is music and that

we are a chord in this concert.”

*****

Read more: