In 1827, the seminal German humanist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe—noting that literature was being shared across national borders of Europe and beyond—wrote the now-famous line: “the era of World Literature is at hand, everyone must do what they can to hasten its approach.”

We consider this quote the start of a global literary consciousness that shifted the conception of literature from a reflection of national character to a global phenomenon reflecting the (purportedly universal) human spirit.

But since any piece of literature could fit under its umbrella, “World Literature” is not so much a genre as perspective. World Literature presumes that all works of literature, no matter where they are from, nor in what language they are written, can be viewed side by side, and can be compared and contrast. David Damrosch puts it best, saying that “world literature is not an infinite, ungraspable canon of works but rather a mode of circulation and of reading, a mode that is as applicable to individual works as to bodies of material, available for reading established classics and new discoveries alike.”

Goethe conceived of World Literature as the exchange of primarily Western European literatures. In the three hundred (or so) years since his letter, World Literature has expanded far beyond the Western Literary canon. But the distinct bias in global publishing, favoring the languages of economically prosperous countries, persists.

The urgency for a more diversified literary landscape should resonate most with translators. Translators find themselves in service to the creation of a world where boundaries—both political and cultural—are permeable, porous. The demand for World Literature has never been higher, and translators, once considered an afterthought, are now being regarded as artists. During a panel for Asymptote‘s three-year anniversary in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Karen Thornber, chair of Harvard’s Comparative Literature department, explained that when she was a student, translation was considered an inferior way of reading a novel, while today translation is a critical element of the comparative literary process. This is good news for all of us.

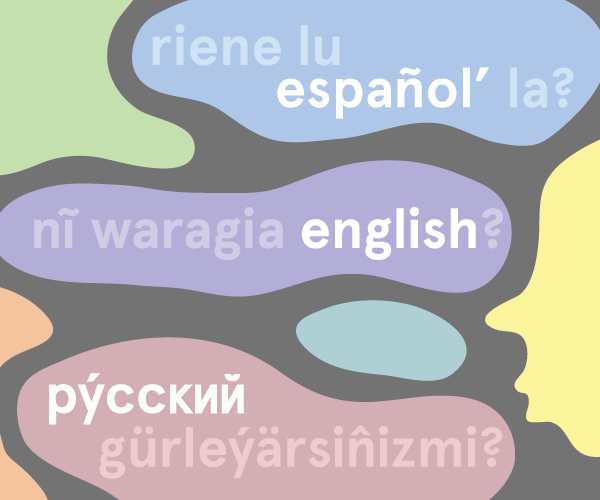

But while globalization has been a boon for translators, it has provoked a troubling trend in countries that do not have the benefit of being in the center of the global stage. In Africa, for example, young writers overwhelmingly write in English, French, and Afrikaans, languages of colonizers, so their work can be recognized and compensated on global terms. Most major African literary awards only bolster this problem by accepting only English works. This problem is not specific to Africa but exists anywhere minor languages feel the economic and social dominance of major ones (such as Central Asian languages that exist under the shadow of Russian and Indigenous American languages under threat from Spanish and English).

This troubling trend, if not reversed, could mean the end to hundreds, if not thousands, of lesser spoken languages, and therefore, their literatures. This would be a fundamental blow to World Literature, and undermine the gains that translation has made in the past decades. Now more than ever before, the skills of translators are considered an art form. Translators must use their newfound prestige to prevent globalization from crushing smaller languages. By diversifying the body of languages we translate from, we can preserve the gains we have made, and make translation even more relevant than it is now.

The very act of translation heightens the vitality of the languages it connects. It broadens the array of people that the source language can speak to and transforms the function of the target language. The world that Goethe envisions is a world where literatures complement and complicate each other. When larger languages drown out smaller ones, World Literature loses the crucial elements that make it an endeavor worth pursuing.

The era of World Literature is perennially at hand. Just as World Literature has changed since Goethe first conceived it, we need to make the effort to change it from its current form. In order for World Literature to diversify, translators must first make the effort to diversify both in the regions they choose their work, and the languages they choose to translate. In doing so we can add to the vitality of global literature, while demonstrating that translation is not just an art form, but a way to build global equality and understanding.

Read more: