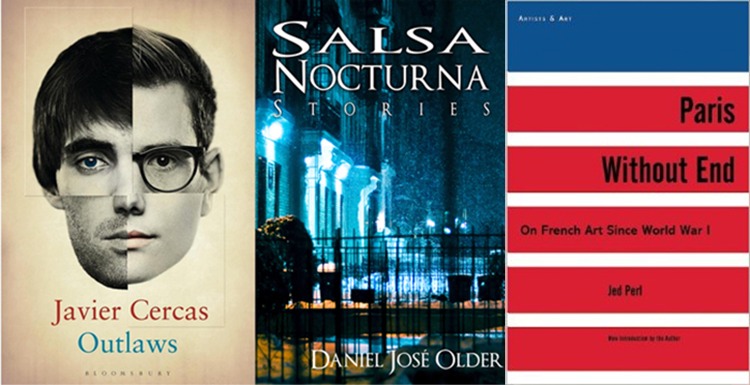

Ellen Jones (criticism editor): For my birthday this year I was given Outlaws (Las Leyes de la Frontera) by Spanish author Javier Cercas, translated by Anne McLean. I immediately broke that fundamental rule and judged it by its cover—the Bloomsbury hardback has one of the most exquisite jacket designs I’ve seen in a long time. Fortunately I wasn’t disappointed by what was inside. Inspired by the life of Juan José Moreno Cuenca, a notorious criminal known as “El Vaquilla,” the narrative follows a gang of teenagers led by a soon-to-be famous juvenile delinquent styling himself “Zarco.” At the novel’s core is the relationship between Zarco, the media persona, and Antonio Gamallo, the real person behind bars. In post-dictatorship Catalonia where the after-effects of Franco’s rule are still being felt, the gang members are divided by class and their fates apportioned accordingly. The novel is narrated entirely through reported speech, allowing Cercas to explore the unreliability of memory through a series of voices that are always measured and deliberate (The Telegraph’s description of it as a “rip-roaring crime romp” seriously misses the mark).

I also read two books this month set amongst New York’s Latino community. I first heard of Daniel José Older via a short video posted online. The video, about why publishers shouldn’t italicise Spanish words in U.S.-Latino fiction written in English, made me chuckle as well as think. It inspired me to look up Older’s debut “ghost noir” collection Salsa Nocturna. Set in a New York where the dead (and the half-dead) live surprisingly human existences that mirror the bureaucracies, injustices, and heartaches of the living, this series of linked stories addresses pressing social issues with the lightest of touches. The dialogue reads almost like a television script—witty and fast paced, liberally smattered with slang and with Spanish. Although speculative fiction is not my usual reading material, I look forward to reading some of Older’s more mature works.

Next I read Francisco Goldman’s Say Her Name, an autobiographical novel about the death of his wife, Aura Estrada, in a freak bodysurfing accident in Mexico. Regardless of how much is fact and how much fiction, this much is clear—Goldman’s grief and devotion pour from every word. He examines the extent of his guilt in a narrative that is beautifully, almost unbearably sad. Memories of his young, intelligent, beguiling wife and the years they lived together between New York and Mexico City are woven together with descriptions of the private chaos he experienced after her death. Having finished it only days ago, I’ve already bought Goldman’s more recent volume, The Interior Circuit, which is sitting on my bedside table.

Tim Ellison (intern): This month I’ve been reading the twenty-fifth anniversary reissue of Jed Perl’s classic Paris Without End: On French Art Since World War I. The essays on under-appreciated artists such as Derain, Léger, and Dufy are compelling (the piece on Hélion was my personal favorite), but I’ve been more intrigued by Perl’s readings of well-known artists in the latter halves of their careers. Matisse’s withdrawal from Paris, his gouaches découpés, and his design for the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence reveal an indomitable spirit that refused to be content with past triumphs. There is something heroic about this fearless commitment to one’s own imagination, despite the protestations of the critics. On the other hand we have Picasso, whose interest in his own work tended to sag somewhat until revived by new passion (often a new lover). Yet even in those stretches of ordinary time he went on producing “Picassos.” Is this persistence an example of heroism, or merely business-savvy craftsmanship, or aren’t those two as far apart as we romantics would like them to be?

I’m also currently reading W. S. Merwin’s newest collection, The Moon Before Morning. In a genre between still-life and landscape, Merwin evokes the genius loci of his Hawaiian home and reflects on the fragility of the moment and the endurance of memory. There are some anecdotal poems of the my-father-and-I-didn’t-get-

I’ve read some critiques of Merwin’s refusal to use punctuation, as though this were an old man’s fancy rather than an essential element of the master’s craft. But Merwin likes to twist syntactical units at the midpoints and ends of lines, the very places where punctuation would be the most helpful, so that you never can tell exactly how the poem should flow. Thus the reader is invited to measure the poem for herself, to carefully assess how space relates to time and how spirit (the breath) relates to the letter. One enacts, through reading aloud, the very theme of the book.

Read more: