For an exclusive Asymptote blog interview with Naja Marie Aidt, click here.

It’s strange to meet you here, after so many years, and to still feel disturbed just being near your body. The way you’re settled in the chair like a large contented animal, like a large wild cat licking itself in the sun, or an elephant bathing in a river, like a person resting on top of another after pleasurable sex, it has an intimidating and shameless effect on me. My complete attention turns toward you and I’m unable to relax. It’s as if I am overflowing my own banks.

The rhythm of my heart became irregular. I froze. I sweated. I was unable to control my facial expressions. A thin man, who kept taking off and putting on his glasses, lectured, apparently about economic growth in the Far East. You’re sprawled in the armchair in front of me and I could see the nape of your neck, the light skin of your throat, your strangely rounded thighs pressing against the black fabric of your pants, and your thick wide hands relaxed in your lap. I could see your breathing in your back, how it blew you up a bit, how your shoulder blades slid away from each other a little before coming together again. And the entire time I saw you naked in front of me; it frightened me, like a kind of obsession, something inevitable, a clear image of your whole body standing in my bedroom, a smile slowly spreading across your face and then your head sliding back at an angle, really enjoying it, while your red and blue prick shines wildly between your legs. The whole time I saw you naked sitting in that arm chair in front of me, and reflected in the mirror hanging on the wall in front of you, I saw you smile at something someone said, or I saw you close your eyes, pressing them shut in an odd grimace; that’s also disturbing: the way you take up so much space, the way you always make those grimaces whenever you’re with complete strangers. But I’m no stranger. And I am a stranger. It’s been so many years that we’ve definitely become strangers to each other, but we’ll never be complete strangers to each other. That’s what makes it so unbearable. It makes me sick just looking at you, and yet I couldn’t look away. Then you slide your hand up and rest it on the back of your neck, lightly supporting your large head, completely relaxed. You turn your face so that I can see your nose, a little of one eye, half your mouth, the wrinkled but surprisingly moist skin over your jaw. And in the mirror on the wall I see the other side of your face, where the skin of your jaw is tight and smooth because you’re turning your head slightly to the other side. Perhaps someone has said something funny. Because now you laugh out loud, hoarse, and unabashed, your mouth opening, and even your teeth I know, every one of them, the wet gums, and the brown discoloration at the back of your bottom teeth. I’m shocked. Your laughter shocks me. It feels like an animal has snuck up on me and suddenly it’s close, ready to attack. I accidentally utter a peculiar sound from deep within my throat. I adjust myself in the chair, pressing my hands between my thighs. You’ve thrown your leg up over the armrest, and now you swing your foot and shin rhythmically back and forth. Your shoes are black and shiny. I can see your socks. The leg is swinging. Your hand leaves the neck and reaches for the coffee cup on the table in front of you. Your lips purse together as if to kiss and slurp from the cup. You bend forward, putting it down again. Loudly you clear your throat. A muscle begins to twitch just above my knee like a painless spasm. And now I suddenly notice how cold my feet are, almost numb, at least the toes are, way down in the thin boots. And now I notice how warm my face is, it must be red and blotchy, it’s throbbing behind my eyes, and my mouth is dry. When there’s a break a little while later, I get up carefully; I notice how stiff my legs are when I walk the few yards to the table with water. I spill some as I pour it. Your gaze at my back. No doubt, unintentional. I stumble out of the room and sit on the toilet breathing fast for a long time.

During lunch you come over to me and ask a few simple questions. It’s been a long time. How’ve you been? Your gaze searches in all directions as if you were dreaming with your eyes open. I hear myself answer. I pour some whole milk in my glass. You say something else and laugh. You lay your hand on my shoulder and give a little pull before going over to your seat at the other table. I drink all the milk. It stings where you had placed your hand. As if you had made an imprint on my skin. And that’s exactly what you’ve done. Like no one else you have made an imprint on my skin. I’m full of scars. I’m not ungrateful to you. It’s part of my life’s great experiences. It’s hard to explain. It’s chemistry. And I remember it as a situation without willpower, which was certainly so full of will. For your flesh. Back then. The white cloth of the sheets clenched in my fist. Your hand lifting the cigarette to your mouth. The sound of water sliding down your throat. My own wide open eyes. The skin on my back. When you bend over it. And this scent from you hanging in the air even though you’re now sitting several yards away eating quickly with concentration, quite civilized, but with a hidden, unruly greediness; the scent of dry tobacco before being rolled into cigarettes, the scent of perfume that’s nearly washed off, the scent of booze digested long ago, ecstasy that burnt out long ago, and all that’s left is a little prickling nausea. That scent. Which I was drawn into. Which I adore. But not without resistance. Because I know so well that you bring imbalance. I know this deep within my body. Just like I know that I can’t tolerate milk. And that’s what made me so desperate and angry. There’s only you. And I vanished. It’s physics. It’s like a tree that moans when the branches rub against each other but they can’t move away. One of them wears out until it falls down, only to decay on the ground. It’s physics that determines which branch must surrender. I fell long and hard. Now you put the fork and knife down and suppress a burp. I glide my tongue over the mucous membrane the milk has left in my mouth. My hand lies heavy and relaxed on the table. You bend toward the woman next to you and say something to her. She smiles confused and looks at you with large eyes. I have a violent desire to cough. I fall long and hard, a gorge has opened in me down through the throat, ribcage, stomach, I tumble with the racing blood and see my entrails sweeping by. I come to the sizzling stomach and it whirls around in a maelstrom. Dissolving acid around and around. My eyes wide open. The hand squeezing the white cloth. I will shout something hurtful and inappropriate at you. And then I feel at last I can cough. But it turns out that I throw up. I straight out throw up. All over the table and myself; it must’ve been the milk. I hear a loud ringing in my ears, and then I breathe in with a wheezing whistling sound. Then it gets completely still. You wipe your mouth with your napkin and turn your head slowly slowly to look at me.

***

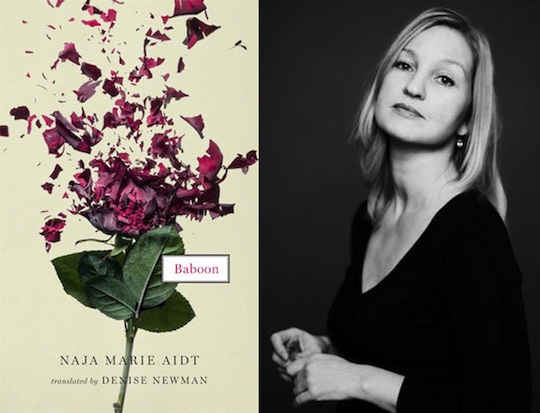

Originally from Greenland, Naja Marie Aidt is a Danish poet and author with nearly 20 works in various genres to her name. She has received numerous honors, including the Nordic nations’ most prestigious literary prize, the Nordic Council’s Literature Prize, in 2008 for Baboon, and her work has been translated into several languages. Her work has also been anthologized in the Best European Fiction series and has appeared in leading American journals of translation.

Denise Newman is a translator and a poet who has published three collections of poetry. She has translated two books by Denmark’s greatest modernist author, Inger Christensen, and her work has appeared widely, including in The Denver Quarterly, Volt, Fence, New American Writing, and ZYZZYVA.

Read more: