Antony Shugaar, translator, writer, Asymptote contributing editor

I remember reading a science fiction short story many years ago in which a disgruntled author of historical novels gets his wish to witness the crucifixion of Christ. The plot’s twists and turns escape me now, but I know the final outcome is that he winds up crucified on a secondary cross, an all-too-eager witness to the truth behind the familiar version.

Historians are constantly pawing through the rubble of memory, language, and inference in search of an unproven and unprovable truth. Death—of course—intervenes, as does the slow grind of time, but memory and perception get in the way, too. So does institutionalized meaning: once you’ve heard “By the shores of Gitche Gumee, By the shining Big-Sea-Water,” you can never unhear it.

There’s a cottage industry founded on making you hear the unforgettable literary earworm: Emily Dickinson’s opus, for instance, can be sung to the tune of “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” while Frost’s “Stopping By Woods” goes (disconcertingly) well to the mambo beat of “Fernando’s Hideaway.”

These are garish and grotesque instances of the static interfering with a classic. Dante’s Inferno is a wonderful piece of poetry, and I had the particularly good fortune to hear it teased out in a series of evening classes at Perugia’s Università per Stranieri that were taught by a brilliant and slightly venal politician and literary scholar: himself practically a character from Dante. But I’ve known many Italians over the years who, no matter how much they love the Divine Comedy, can’t help but think of that monumental work of sidereal depth and human empathy without hearing the line “Vuolsi così colà dove si puote ciò che si vuole,” a sort of fourteenth-century “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers” uttered by Virgil and announcing the ineluctability of divine will (to be reduced by generations of high school students to comic doggerel).

The familiarity of the classics is both their strength and their downfall. That familiarity invites contempt and penciled-in mustaches. But it also reflects their fertility, like a yearly-flooding Nile bringing rich literary soil to generations of young imaginations.

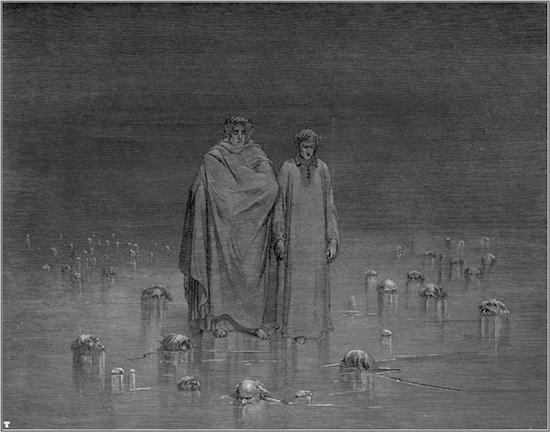

Just as time travel would leap past a historian’s chief stumbling block—the inability to see her subject—so do readers sense that there’s always a struggle to see past the patina, to peer under the crust of accretion on what was once actually new. The Divine Comedy was a brilliant effort to achieve something even beatniks would have thought overambitious: to sympathetically conceive of the places where all souls that have ever lived now commingle, still distinct and yet transfigured.

The visions are stunning, but familiarity fogs the glass.

And that’s why the possibility of new translations of familiar classics is so alluring. The idea that someone can bring us a “director’s cut” of a classic is manna from literary heaven. It entails risk, of course, and every translation is in a sense a destruction of both the existing work and its other translations.

The benefit of new translations of classic works lies in the fact that sometimes the old ones are dated and inaccurate.

Thus, a new Italian translation of The Great Gatsby has finally eliminated a number of painful missteps in the great translation by Fernanda Pivano. One of the most glaring is this: “Così continuiamo a remare, barche contro corrente, risospinti senza posa nel passato.” In her rendition, “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past,” describes not a sailboat, beating into the wind against the relentless current of time, but a rowboat. “So we row on,” goes the Italian, and has gone on, unintentionally echoing with a “gently down the stream,” since 1950.

Some classic works defy new translation. I’m not 100 percent sure of the details, but what I’ve heard about Hermann Broch’s The Death of Virgil is a story that, as the British might put it, “if it isn’t true, it certainly ought to be.” Broch wrote the book in German and then labored mightily with the American translator (who was also his lover), to publish it in English. After its success, the book took many years to appear in a German edition because there simply was no “original” German text. This was a work of literature caught forever at the mirror’s edge, half in and half out of its native language. Now there’s a version that belongs in Jorge Luis Borges’s personal library of impossible translations.

***

EJ Van Lanen, founder and publisher of Frisch & Co. Books

In a recent article in Russia Beyond the Headlines, Oliver Ready was interviewed about his new translation of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. He wrote out his translation longhand: “In fact, I wrote out every sentence—it was a kind of experiment, I suppose. I did this to get away from the computer and in the hope that the translation would come out better if I wasn’t tempted to edit myself after every phrase.” And he tried to make the translation sound “modern, but not contemporary” by avoiding words that appeared after the 1960s.

Both of these facts are remarkable, and they illustrate the discipline and dedication that’s necessary to complete the difficult task that is literary translation, a difficulty that Mr. Ready has doubled, or tripled by taking on a book that has already been translated into English, and so successfully.

Re-translations are an important part of the modern literary landscape. It seems every season we are reintroduced to a translated classic, whether it’s Susan Bernofsky’s Metamorphosis, Edith Grossman’s Don Quixote, or Lydia Davis’s Madame Bovary.

It’s easy to imagine a whole series of demands or constraints that might bring about a re-translation, all of them valid and necessary, insofar as they can be called either of those things: the language changes, a translation falls out of fashion, a translator wants to do their version of Cortázar, a publisher sees an opportunity, and on and on.

I’m of two minds on this phenomenon.

As a publisher of translated literature, I can see the advantages and allure of re-translations: they’re a good source of revenue for publishers—they tend to sell; they’re catnip for book journalists, directing a not-insignificant amount of attention to translated fiction; and they give translators a chance to take on a favorite work or author, to wrestle with Big challenges, which must be unimaginably exciting and rewarding.

And then as a reader, and when I’m feeling more cynical, re-translations can feel like publishing’s version of the big-budget sequel: a familiar and well-liked property, slightly re-worked, that has an established audience—the safe bet.

But even when I’m not feeling quite so cynical, I can’t help but think that the energy, money, and resources spent on producing another edition of Crime and Punishment, not to pick on Mr. Ready, might be better spent in the riskier pursuit of trying to find, translate, and publish tomorrow’s Dostoevsky or Lispector, or whomever. Our view of the world’s literature is relatively limited; given our circumstances, discovering new voices is more urgent than uncovering shades of meaning in books that have established their reputation in English.

Then again: I’m very much looking forward to Damion Searls’s upcoming re-translation (and first complete translation—it’s complicated) of Uwe Johnson’s Anniversaries in 2017.

*****

Featured image Cocytus, from the Divine Comedy illustrations, by Gustave Doré, 1857