Prose and I are having a moment.

I don’t mean this in the glamorously ephemeral, André-Leon-Talley sense; I mean this in the emotionally fraught, tightlipped-dinner-party sense. I just can’t seem to enjoy it as much as I have in past twenty-odd years of my life. I find myself bored by the contrivances of exposition; I roll my eyes at narrative inventiveness, and quote-unquote characters and their grievances simply exhaust me.

I haven’t always been this pretentious: I’ve been struggling with this for about three months, and I’d like to think of it more as a passing phase. My last review of F was part of my ongoing effort at reigniting my love for fiction—but even so, I can’t beat the dragging feeling I get reading complete sentences, in succession, expressing something like a (gag!) plot line.

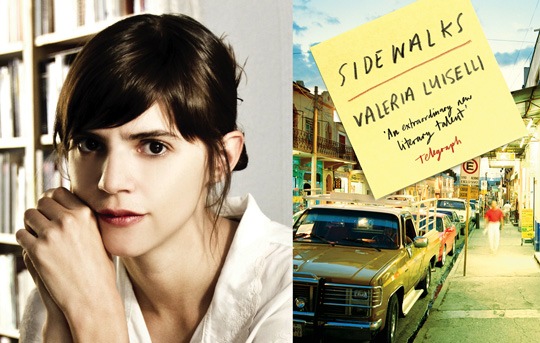

Enter Valeria Luiselli’s Sidewalks. To be fair, this is not fiction: this book, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney for Coffee House Press, is a slender collection of essays. But I’d consider anything lacking enjambment, caesura, or anapest “prose enough” for me.

And these essays—written in lovely, funny, clearheaded prose I was set upon hating—proved the perfect corrective for all my prosaic bellyaching. Her essays are philosophical, smart, wandering. They feel natural, uncontrived, relaxed. Reading her writing, I felt my paralyzing skepticism of syntax and cohesion begin to relax.

Valeria Luiselli is an interesting writer—she’s based in New York City and grew up in South Africa, yet a majority of her writing appears in Spanish. It’s clear from her essays she’s widely traveled, and widely read (perhaps the two are synonymous). She teaches creative writing and is pursuing a Ph.D. in comparative literature. Reading her bio online (and recounting it for a review), she seems like quite the nomad on paper—and this nomadism is omnipresent, really, in her writing: perhaps the unifying theme of Sidewalks, a collection of essays so gorgeously light and meandering that it really appears more as a single essay divided into parts, is its dedication to thinking about what it means to inhabit a spot, in the most simple, rudimentary sense.

In these essays, Luiselli stays someplace, then leaves. How on earth can we be someplace, physically, and share a street, city, or a building with people; how can we build a city or travel on a road or canal? What is it to abstract this principle of neighborhood, city, nation, and how do we consolidate this abstraction with the doorman outside, the commute, the flowers we put above a decomposing body?

The first essay in the collection is perhaps the most frequently referenced. Luiselli is in Venice, looking for one grave in particular: that of poet and essayist (and fellow nomad) Joseph Brodsky. In the course of the essay, not much happens (spoiler alert: she finds the grave, hardly marked), but the reader accompanies Luiselli as she wonders why it’s important to see this grave in the first place. Later, in another essay, Luiselli looks at old maps of Mexico City—perhaps the greatest example of decentrality and urban sprawl—and wonders: how are our spaces planned? Or, later, Luiselli tackles the modern trope of the flâneur, a now-defunct walker, and reinvents it with the meditative detachment enjoyed with a long bike ride. She wonders how we got here, and we join her, looking.

I didn’t mean to ask so many rhetorical questions in the course of the review, but they’re all I have. I know that Luiselli doesn’t have the answers, either. But her essays are marked with a considered curiosity, just light enough to avoid the strain I typically sense when reading exposition, and I find myself wandering, delighting in not-knowing. I may get lost in the city, but I’m enjoying myself.